Recently, Russia initiated its first ever joint military exercise with Pakistan. A few months earlier, in a first, Russia agreed to sell Mi-35 attack helicopters to Pakistan. Numerous reports also suggest that Pakistan is reportedly in talks with Russia for the purchase of Su-35 combat aircraft. The sale of defense equipment to and military exercises with Pakistan indicate a significant shift in Russian foreign policy.

To state that Russia and Pakistan were Cold War enemies is an understatement. Approximately 14,000 Soviet soldiers were killed and more than 35,000 were wounded in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. Many of these causalities were the consequence of mujahideen forces that received significant support from Pakistan and the United States. Even after the end of the Cold War, Pakistan was an important U.S. ally. As a consequence, the defense relationship between Russia and Pakistan was very minimal. That seems to be changing now.

The perception that evolving India-U.S. defense relationship, at the expense of India-Russia defense trade, may have contributed to the shifts in Russian policy toward Pakistan is erroneous. Contrary to popular opinion, India has spent more money on importing Russian military equipment in the recent past. Calculations based on data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) show that from 1994-2004 India purchased approximately $11.43 billion worth of defense equipment from Russia. After the India-U.S. nuclear agreement in 2005 until 2014, arms exports from Russia to India amounted to $20.70 billion. From 1999 to 2003, India received about 23 percent of Russian defense exports, which increased to 24 percent in 2005-2009 and to 39 percent in 2011-2015. In terms of both absolute numbers and as a percentage of Russian exports, India has procured more from Russia in the last ten years than the preceding period. Higher rates of economic growth and growing security concerns prompted India to diversify its defense acquisitions from various countries including the United States. However, such diversification did not happen at the expense of India-Russia defense trade.

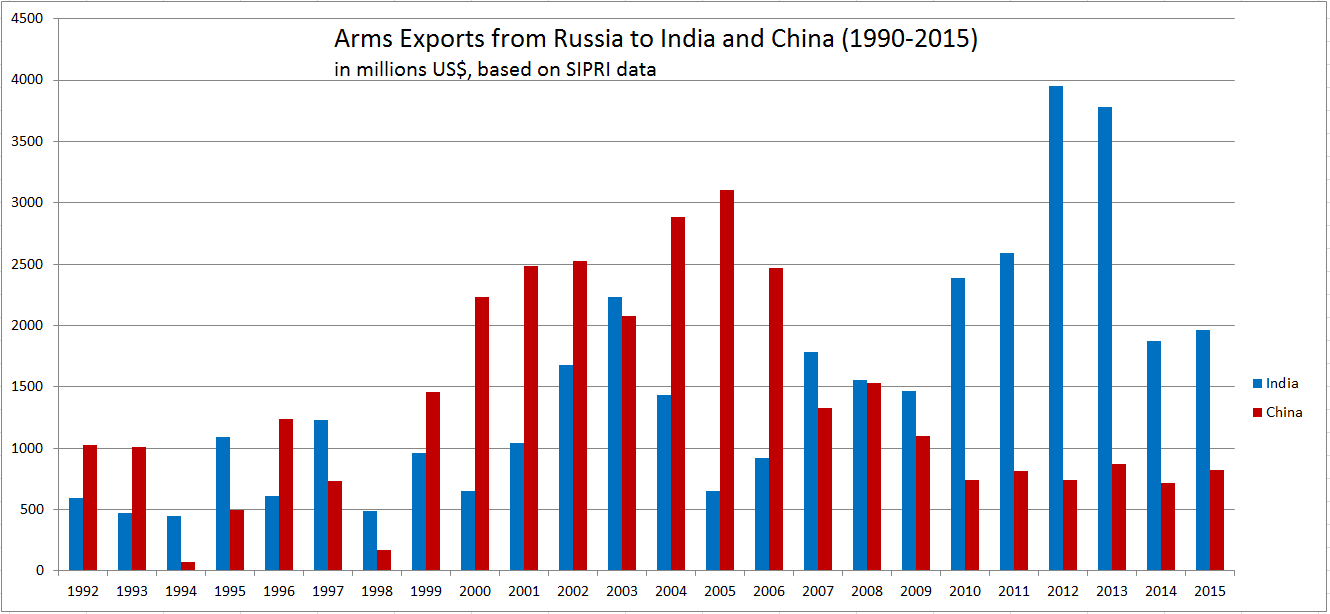

The assessment that the shifts in Indian foreign policy caused the changes in Russian approach toward Pakistan is also based on the assumption that Russia always factored India’s security concerns into its defense trade. An examination of the SIPRI data does not bear out this conjecture. For instance, the figure below clearly demonstrates that for a majority of years during 1992-2006, Russia exported more arms to China than to India in terms of value. Only since 2007 has India consistently overtaken China.

The Russian sale of defense equipment happened in spite of a clear understanding that China and India have a border dispute. The rapid decline in China-Russia defense trade after 2006 is a consequence of significant enhancement in the domestic capacities of China’s defense industry, not a conscious strategic choice by Moscow. Further, it should be noted that Russia continues to sell critical defense equipment to China. For instance, Russia has agreed to sell 24 Sukhoi Su-35 aircraft to China. More recently, news agencies have reported that the development of the Chinese fifth-generation J-20 stealth fighter may have been possible only with substantial Russian assistance. Clearly Russia and China have been collaborating very closely on defense and security issues. Such mutually profitable defense cooperation between Russia and China continues in spite of anxiety in India about growing power asymmetry in favor of China.

Similar rational calculations, rather than a sense of hurt over India’s policy, are guiding Russian policy toward Pakistan. Energy resources and defense equipment constitute critical components in Russian exports. Oil prices, which touched about $140 per barrel in 2008, are now hovering around $45 per barrel. This dramatic fall in oil prices generated stress on Russian exports. On the defense exports front, there are long term challenges. Along with India, important destination countries for Russian arms exports include China, Algeria, Vietnam, Venezuela, Azerbaijan, Iran, Syria, Myanmar, and Egypt. Many of these countries are witnessing shifts in their domestic politics, and some are altering their external postures.

During 1999-2003, China received 44 percent of Russian defense exports, which declined to 35 percent in 2005-2009 and reduced further to 11 percent during 2011-2015. China, which was a significant recipient of Russian military equipment, has built domestic defense manufacturing capacities and has now emerged as the third largest defense exporter in the world.

Meanwhile, Vietnam’s relations with the United States have witnessed dramatic improvements in the recent past. Washington lifted the embargo on the sale of lethal military equipment to Vietnam during President Barack Obama’s visit to Hanoi this year. Vietnam will be looking to purchase high-end defense equipment from the United States in near future. Similarly, with the U.S. completely lifting sanctions, Myanmar will be looking for diversified military relationships with Western countries.

Venezuela’s economic collapse has triggered a humanitarian crisis due to severe food shortages. Given the scale of the crisis, it is doubtful if Venezuela will purchase defense equipment with the same vigor as it used to do in the second half of the last decade. Syria is experiencing a civil war and Russia had to step in with its military to support a friendly regime in Damascus. The intervention in Syria also served as an advertisement for Russia weapon-systems. However, Syria is still some distance away from genuinely purchasing Russian military hardware in large numbers. In Egypt, Russia has to compete not only with the United States but also with the other European powers such as France. Similarly, in Iran, which was under sanctions till recently, Russia will have to contend with the enthusiasm that China has been displaying.

Not surprisingly, given these factors, Russian arms exports have started to show a downward trend since 2011.

To stem further decline, Russia is working its way back into old markets, such as Iraq, as well as expanding into new markets and sees Pakistan as a lucrative prospective client. Pakistan is the seventh largest importer of defense equipment in the world with China and the United States as its leading suppliers. The ecosystem to sustain a domestic defense industry is still in its infancy in Pakistan and its relations with the United States in the recent past have been experiencing some strain. Therefore, there seems to be a growing convergence between Pakistan’s need to diversify its military procurement and Russia’s need to find new defense markets. It is this convergence that has prompted the shift in Russian policy toward Pakistan.

In doing so, Russia is taking a calculated risk that India will not cancel existing defense contracts in large numbers as retaliation for Russia’s new policy toward Pakistan. This bet is based on three assumptions. One, decades of defense purchases in large quantities have ensured that India will be dependent on the Russian defense industry for spares and maintenance for a considerable length of time. Two, since India is not a member of the United Nations Security Council, it will hesitate to antagonize a veto power that had come to its rescue on earlier occasions. The mere threat of censure on international platforms for alleged violation of human rights may compel India to reach out to Russia. Third, Moscow will continue to offer the sale of high-tech strategic defense equipment, which the United States and others may be reluctant to part with.

Given these developments, India need not feel guilty about failing to respond to the challenges confronting the Russian defense trade due to shifts in procurement patterns of countries such as China and others – that is neither the function of India nor should it be the objective. Instead of indulging in unwarranted self-flagellation, it would be prudent for India to focus on using trilateral and multilateral frameworks to create financial constraints for Pakistan’s defense imports. More importantly, a quick progress on strengthening domestic defense manufacturing is an urgent necessity.

Sanjay Pulipaka works as a Senior Consultant with the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), New Delhi. The views expressed here are personal.