Every year, usually in early March, more than 10,000 people flood into Wat Bang Phra, a Buddhist temple about 30 miles west of Bangkok famed for its magic tattoos and amulets. The participants enter the dusty temple grounds under the early morning sun for a heady festival revolving around a sacred tattoo tradition known as sak yant.

Those who make the pilgrimage to the temple hope to recharge the magic coursing through the sacred geometrical patterns and figures inked into their skin through a ceremony called Wai Kru (“paying respect to the teacher”). Starting at the designated time of 9:39 am sharp, monks lead the rite with a series of prayers and incantations.

What may sound sober takes a surprise turn as the energy of the crowd builds. One after another, devotees enter a trance state known as Khong Khuen (“magical force rising”), in which they jump, scream, and charge headlong, arms flailing, toward the front of the temple grounds where the monks sit and oversee the festival. They have become possessed by their tattoos, which force them to embody the tigers, crocodiles, mythical Himapant animals, and Hindu gods depicted in the designs etched into their skin. Not even camera equipment is safe during this mayhem, which can be seen unfolding here.

A phalanx of soldiers and paramedics guard the temple shrine from the onslaught of tattooed devotees, bringing them out of the trance by rubbing their ears. As the festival concludes, the monks lead a prayer before the crowd rushes toward the stage to be blasted with holy water from a high-powered hose. The devotees leave, confident their tattoos have been sufficiently charged with magic again.

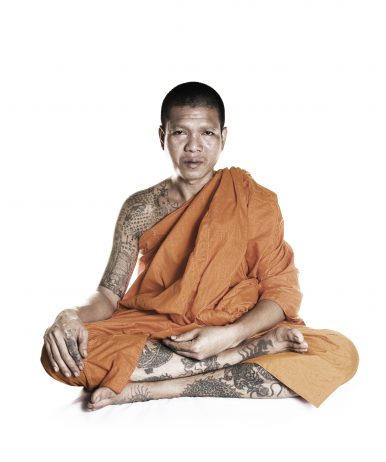

In reality, “sak yant do not lose their power over time,” Aroon Thaewchatturat, who took the photographs for Sacred Skin: Thailand’s Spirit Tattoos, told The Diplomat. “What goes down is the mindfulness of a tattoo wearer. This is why, once a year, the Wai Kru ceremony takes place in order to pay homage to the current and late tattoo masters. The current master who represents the past masters will bless all followers.”

Photo credit: Aroon Thaewchatturat

A Thai History of Ink

This spectacle, widely known among travelers in Thailand today, is linked to a tradition with ancient roots in Southeast Asia. “Sak” means “tattoo,” and “yant” means yantra, a mystical diagram found throughout Dharmic religions. These tattoos draw inspiration from Buddhist, Brahman, and animist imagery, and incorporate sacred geometry and magical incantations (kata) written in the Khmer version of Pali Sanskrit known as Khom.

“We use the ancient Khmer language in sak yant because Thailand was once a vassal state of the Angkor Empire,” Ajarn Neng Onnut, a renowned, Bangkok-based sak yant master who has tattooed Steven Segal and Brooke Shields, among other luminaries, told The Diplomat. “Sak yant was influenced by the Khmer language since around 1,200 years ago. The language has no power in itself. But power comes from the [tattooing] ceremony.”

While historians debate exactly when Thais began tatting up, the tradition is believed to be between one to two thousand years old, with the first concrete evidence dating to the time of King Naresuan Maharaj. During the golden age of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1351-1767 CE), warriors took to the battlefield clad in suea yant, or shirts covered in yant designs meant to protect them. Officials and civil servants from the period also wore sak yant to signal their status.

Today the sacred art form is most alive in Thailand, and to a lesser extent in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Unlike in Japan, where a rich tattoo tradition is still struggling to shake off its stigma, a growing number of Thai people from all walks of life are inking up.

“Generally, sak yant have been worn by working class people in Thailand though this has changed in recent years,” said Tom Vater, the author of Sacred Skin: Thailand’s Spirit Tattoos. “Since Western celebrities got inked, Thais in the public eye have followed suit and the tradition now has some traction amongst some younger middle class people as well.”

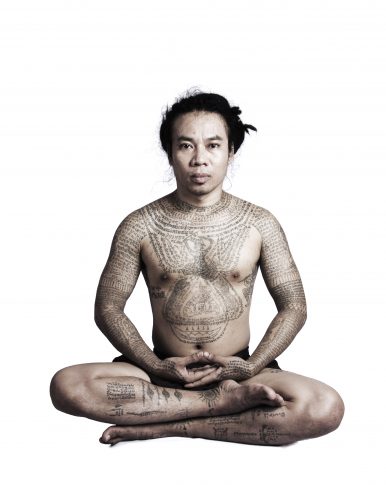

Photo credit: Aroon Thaewchatturat

Lost in Translation

As recently as the 1990s, sak yant was still very much a Thai phenomenon, aside from a small number of foreign Muay Thai fighters or temple devotees who found their way into an ajarn’s studio or temple. The late monk and tattoo master Luang Por Phern Tidtakuno — whose statue now stands on the grounds of Wat Bang Phra — played a huge role in spreading the word about sak yant, which has become wildly popular among foreigners in recent years.

“Ever since Angelina Jolie had her back inked with Thailand’s sacred tattoos, the sak yant culture has been steadily spreading beyond Thailand’s borders,” Vater said. “And while celebrities like Brooke Shields, Michelle Rodriguez, and Steven Seagal have also acquired sak yant in recent memory, the annual Wai Kru event at Wat Bang Phra is attended by more and more foreign devotees every year.”

The Thai culture ministry “called for a ban on foreigners receiving religious tattoos in 2011 but this has not been enforced,” Vater added. “The issue is not sacred tattoos per se, but the placing of such tattoos on inappropriate parts of the body.”

Far from a mere aesthetic concern, the placement of a spiritually charged sak yant is crucial. In Southeast Asian culture, the head is considered the holiest part of the body, which is seen as increasingly base further down. Enough foreigners have riled pious locals by getting religious icons etched into their legs that 15-meter billboards have been placed along the highway leading from Suvarnabhumi Airport to Bangkok that read: “It’s wrong to use Buddha as a decoration or tattoo.”

For those ready to navigate the cultural minefield of getting a sacred tattoo, a few specific designs account for the bulk of the sak yant received by foreigners, with the Gao Yord (Nine Pillars) or Ha Thaeo (Five Stripes) atop the list. The former symbolizes the nine peaks of the mythical Mount Meru, home of Brahma and other Hindu deities. It offers a range of protections and is preferred by male devotees who usually have it tattooed on the back of the neck, according to Vater. The Ha Thaeo, he said, bestows blessings for success and good luck, and is typically worn by female devotees on the left shoulder. The five lines are individually unique and vary from one tattoo master to another. For a glimpse of the evocative range of potential sak yant designs, click here.

All of these designs are composed of lines referred to as “bones of the yant”, and can be grouped according to their intended effect, ranging from boosting physical and political power and increasing romantic magnetism to attracting good luck and even being shielded from bullets and blades.

Photo credit: Aroon Thaewchatturat

Getting Inked

Traditionally, each person will receive a sak yant that suits their place in society. This means a different design for a teacher, dancer, artist, or musician. Ajarn Neng explained that he would give a yant focused on protection to a disciple who frequently travels, or a yant meant to increase powers of attraction for a merchant.

“The ajarn (literally ‘teacher,’ or in this context, ‘sak yant master’) or monk who applies the tattoo, decides what is best for the devotee,” Vater said. “But as the tradition becomes increasingly commercialized, and as ordinary tattoo studios churn out sak yant imagery without understanding the cosmology behind the tattoos, and as we increasingly live in a world of instant gratification, many Western visitors now choose which tattoo they want. Thais, for the most part, leave that decision to their ajarn.”

Becoming an ajarn is no small matter. According to Ajarn Neng: “To be sak yant master, you have to practice meditation and study for many years with many other masters. You have to read and write ancient Khmer fluently.”

This is just the beginning. “The science of sak yant is not very popular among Thai people,” Neng continued. “There is essentially a secret society where you have to find a really good master to pass on the knowledge you seek. Some masters test their disciples to make sure they are sincere and would not ruin their reputation.”

Although many go to a temple to be inked, “sak yant are traditionally done by layman tattoo masters,” Thaewchatturat said. “Tattooing is not a monk’s duty, but in a Buddhist society monks are the most respected figures after the Buddha. So some people seek to be tattooed by a revered monk.”

Whether a devotee has opted for a small tattoo studio or an opulent temple, the traditional process of receiving a sak yant follows a similar protocol. After agreeing on the appropriate yant, the ajarn, monk, or ruesi (seer) uses a metal or bamboo rod with a needle attached to the end to lightly hammer the ink, containing charcoal and snake venom, among other ingredients, into the devotees’ skin. Unlike the process of receiving an elaborate Japanese style full-body suit, which can take years if not decades, a sak yant is a relatively brief affair.

“Sak yant don’t take a great deal of time,” Vater said. “Smaller tattoos such as the popular Gao Yord (Nine Pillars) or Ha Thaeo (Five Stripes) take less than an hour to complete. Larger sak yant such as Yant Sua (Tiger Yant) can take half a day or longer to complete.”

The inking process is only a small part of the experience. There’s also a ritualistic aspect, which applies to both the tattoo master and the devotee. “The application of sak yant involves the recitation of katas (mantras) by the sak yant master and the relationship between devotee and master, so the time invested is not just spent getting inked,” Vater added. “It’s important to remember that aesthetic considerations are secondary for sak yant wearers. The image is sacred only when devotees follow certain rules and adhere to the advice of their master.”

For the spiritual essence of a sak yant to remain intact, it is believed that both the ajarn and devotee must live by the “Sin Haa” (five precepts), which are essentially the five basic rules all Buddhists are called to follow in their lives. Upholding at least this modicum of purity keeps the yant from devolving into a state of “Sueam” (entropy). Beyond this minimum standard, there is a host of other rules, depending on the master, from not eating pumpkins or indulging in alcohol or drugs, to never ducking under a specific type of banana tree.

Photo credit: Aroon Thaewchatturat

Stories of Protection

This is a lot to consider before going under the needle. But many are doing just that. Part of the appeal is the lore that surrounds the tattoos. Modern-day wearers make claims of receiving protection or good luck, much like the warriors of yore who charged into battle wearing shirts covered in yant.

“There are many amazing stories of sak yant since ancient times, especially in the Ayutthaya period, when Thailand was fighting a lot with the Burmese. At that time most Thai men had sak yant,” Ajarn Neng said. “Nowadays, some people who have yant have a sixth sense before bad things happen. They can avoid such incidents.”

Vater added: “I have spoken to many Thais and some foreigners who swear on the tattoos’ protective powers. Young Thai nakleng (small-time gangsters) have described to me how they almost got shot or stabbed, only to be saved by their sak yant, which caused the gun pointed at them to misfire or turned their skin to steel so that a knife could not penetrate.”

These tales took on a political flavor during the kingdom’s political crisis of 2008-2010, when the rival factions of the “red shirts,” or supporters of deposed former Primer Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, clashed violently with the “yellow shirts,” or loyalists to King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who recently passed. “In 2009 and 2010, I interviewed several red shirt supporters who wore sak yant and felt that these might protect them in their political struggle,” Vater said.

Between the lore that has built up around sak yant over centuries and the recent boom among Westerners, the ancient art of sak yant remains as relevant as ever.

“Judging by my regular visits to the studio of Ajarn Neng Onnut, there is no let up in the popularity of the tradition amongst Thais,” Vater said. “The studios of sak yant masters around Bangkok remain packed both with locals and foreigners.”

While it is great that sak yant have found favor overseas, this is ultimately a win for the locals. “Working-class people have few means of expression in Thailand,” Vater said. “Their views and culture are rarely seen or heard in the Thai mainstream media, and much of what they consume is dictated from above. Sak yant offer an alternative, a community based cultural ritual that is all theirs.”