China has often been labeled as a “free rider” when it comes to global issues. In regards to global environmental issues specifically, academic scholarship has discussed China’s free riding since as early as late 1990s. Despite its rise, China publicly rejected the idea of forming a “G2” with the United States during the 2008 financial crisis. Why, Beijing reasoned, should China have to take on increased burdens in solving global problems that were not of its making, instead of focusing its resources on dealing with its own domestic development challenges?

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, however, China has been increasingly willing and capable of providing global leadership. As explored in my recent paper, Xi’s call for “new type of great power relations” signaled China’s wish to establish a Chinese version of “G2.” When it comes to climate changes, the U.S.-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change in 2014 clearly indicated the return of “G2” leadership. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry expressed his hope that “this unique partnership between China and the United States can help set an example for global leadership and global seriousness.”

Fast forward to November 2016 after Trump’s victory, and it seems the “G2” is very likely to meet its end, at least on the issue of climate change. This time it may not be China that is unwilling to fulfill its global responsibility, but the United States under President Trump. To be fair, it is not only Donald Trump but the entire Republican Party that tends to deny climate change. However, Trump has taken this general stance to an extreme, once tweeting, “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.”

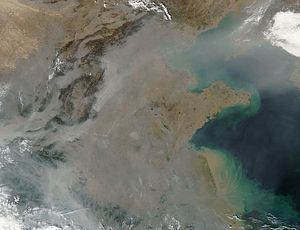

Ironically, 20 years ago, a similar view was also widely shared in China. Back then, many in China argued that the idea of climate change was a Western “trap” to prevent the growth of developing countries and thus China’s rise. However, with China’s environmental crisis emerging from its rapid industrialization, this kind of simplified conspiracy theory is no longer popular in China.

Nonetheless, Beijing is not completely free to fight global and domestic environmental problems. It has to wrestle with the diverse interests of key actors within its political system. These competing trends were revealed in the contrary domestic responses to “Under the Dome,” the popular 2015 documentary on smog. Despite being praised by the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Publicity Department later removed the film from Chinese internet sites. Senior officials in China’s state-owned oil and gas corporation also publicly attacked the maker of this documentary for “lacking of brain power or basic knowledge,” because the film tends to blame environmental pollution on the powerful state-owned enterprises.

With Trump’s presidency, the United States is likely to retreat its leadership in the fight climate change. Will Beijing stand on its own to lead on this global issue? It will need to convince the powerful domestic stakeholders first. For the sake of our planet, it is perhaps time for us to expect China’s global leadership.

Jinghan Zeng is Lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London. His research focuses on Chinese politics with more specific interests in the study of China’s authoritarian politics, political communication, political economy, and foreign policy. He is the author of The Chinese Communist Party’s Capacity to Rule: Ideology, Legitimacy, and Party Cohesion (2015).