The Rebalance author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into the U.S. rebalance towards Asia. This conversation with Emilio Morales – president and CEO of The Havana Consulting Group and Tech, a Miami-based consulting firm specializing in market intelligence and strategy for U.S. and non-U.S. persons doing business in Cuba – is the 73rd in “The Rebalance Insight Series.”

Briefly explain Cuba’s receptivity to Chinese investment and its implications for the United States.

At the moment, Chinese investments on the island are not significantly making an impact. Spain, Canada, and Brazil have more investments than China in the Cuban market. In fact, Cuba is not among the leading countries in Latin America receiving investments from China. The biggest investment priorities of the Asian giant in Latin America are countries such as Nicaragua, Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Mexico, where the free market and the demand for infrastructure expansion and industrial upgrading are very high.

The slowness of the economic reforms undertaken by the Cuban government and the lack of space open to the private sector are the main reasons why Chinese investments are so low in Cuba compared to other Latin American countries where there is a larger market open and where investments strategically offer better returns. Evidence of this reality is that none of the 19 companies approved so far to make investment projects in Cuba’s Mariel Special Development Zone (ZEDM), is Chinese.

However, if the Cuban government undertakes reform at structural levels as did Vietnam and China years ago, then China’s investment interest toward Cuba could grow suddenly. Above all, because in a scenario like this, the U.S. could quickly lift the embargo on the island and Cuba could automatically become the main tourist destination in the Caribbean. This would involve multi-million-dollar investment projects in infrastructure that Cuba needs, where Chinese companies could compete in the market against U.S. companies.

China’s trade with Cuba grew by 57 percent in the first three quarters of 2015 to $1.6 billion. What is the trajectory of bilateral trade relations?

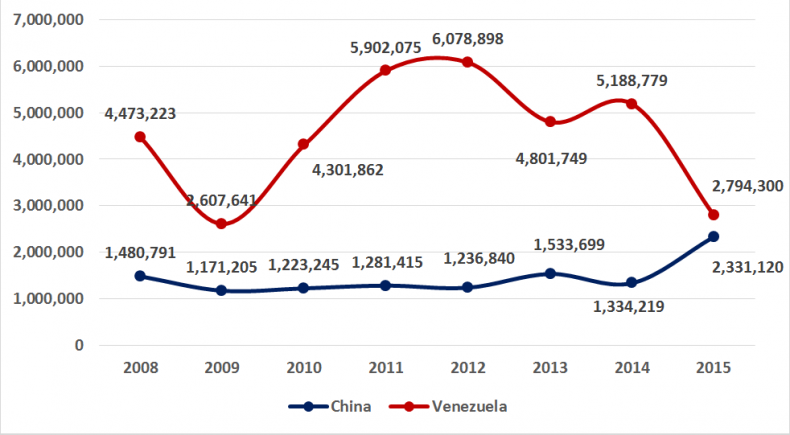

In the last eight years, China’s exports to Cuba remained stable, ranging from $1.17 billion to $1.53 billion annually, not rising above $2 billion until 2015, when the exports were $2.33 billion, $990 million more than in 2014, a growth of 52 percent. These numbers consolidated China as the second largest exporter of goods to Cuba, after Venezuela. These exports were concentrated in technology (the telecommunications sector), machinery, raw materials, and consumer products. However, this is not a growth that responds to a policy of greater Chinese investment on the island, rather it is an alternative taken by the Cuban government to offset the sharp fall-off in trade with Venezuela, a decline of 46.14 percent in 2015. Venezuelan exports to Cuba fell from $5.18 billion in 2014 to $2.79 billion in 2015. This decline has increased in the current 2016, which could raise China to the position of the leading exporter of goods to the island this year.

Figure 1. Historical series of exports of goods from China and Venezuela to Cuba, 2008-2015 (thousands USD)

Which Cuban market sectors are China’s priority investment targets?

China has been very cautious about investing in Cuba. These limited Cuban reforms are still not attracting big Chinese capital. Both countries have signed dozens of agreements in recent years across multiple sectors of the economy. However, most have remained on paper in memoranda of understanding, which do not carry a legal commitment that results in an investment.

In practice little has been achieved. For example, the plan by the Chinese company Geely, to open a car assembly plant in Cuba has not materialized. A similar situation exists with a project for the establishment of a joint venture in the ZEDM, dedicated to the production of Glucometers, Biosensors and other diagnostic equipment. Previously, other investments also remained in limbo, such as an announced investment to build a nickel processing plant for $600 million, the exploration for oil in five Cuban offshore blocks contracted by the China National Petroleum Company (CNCP) in Cuba’s Exclusive Economic Zone (ZEE) in the Gulf of Mexico, and expansion projects for Cuban oil and gas refineries in Cienfuegos and Matanzas. There has been no visible concrete advance either in two other announced Chinese investments for which joint ventures were created: one for a luxury hotel to the west of Havana and the other for a real estate project outside the capital that included the construction of a golf course.

What has worked are some loans granted by China for the purchase of technology and equipment in the telecommunications sector, the purchase of tractors and rail cars, the execution of infrastructure works such as the construction of multi-purpose terminals in the eastern port of Santiago de Cuba and the acquisition of cranes that were installed in the modern port of Mariel, as well as the purchase of bulk carriers and rice drying plants.

What are Cuban government and public perceptions of China’s growing presence in Cuba’s economy?

The reality shows that there are two perceptions: that of the government and that of the population. The government’s view is that the Chinese presence in the Cuban economy depends directly on the depth of implementation of reforms and the scale of the economic opening intended. If the opening is limited and shallow the Chinese investment will be of similar proportions. On the other hand, if the Cuban reforms are profound in the style of Vietnam and China, the investments could take very different dimensions from the current ones, since it would be a scenario of free enterprise and productive forces released.

The perception of the population is that Chinese products are not of good quality; there is no strong connection between Cuban consumers and Chinese brands. Cuban consumers prefer American, Japanese, and Korean brands. This phenomenon occurs because around 2.5 million Cubans live in the United States. Many of them send back to the island branded products that add up to an annual value of $3.5 trillion. These products are sent through shipping agencies or via trips that annually more than half a million Cuban-Americans make to the island with their luggage full of American, Japanese, and Korean products – electrical appliances, cell phones, flat-screen TVs, game consoles, personal computers, clothing, footwear, cosmetics, and other miscellaneous consumer items.

What three strategic priorities in U.S.-Cuba relations should the Trump administration address in the first 100 days of office?

So far President-elect Trump has expressed that he wants a “better” agreement with the Cuban government than the one President Obama applied and has stated that he will wait for the Cuban side to “move ahead” and show measures that really benefit the Cuban people. Otherwise, the president-elect said he would reverse the measures made by his predecessor. The main points of pressure for the Trump administration to apply could be: (a) the migration issue (the Cuban Adjustment Act), (b) compensation payment for the nationalization of U.S. properties at the beginning of the 1960s, and (c) the opportunity for Cubans to enjoy free enterprise, respect for human rights, and the right of Cubans to create organizations other than the Communist Party.

Contrary to what some experts think, Trump can become a catalyst for the process of change that is already happening in Cuba. The economic and political reality of the island in the current context suggests that Donald Trump could have a more favorable position to lift the embargo once Raul Castro leaves power in 2018. Of course, it is clear that if this happened, it would be through economic interests rather than political conviction. For many, this looks like an improbable outcome of a contest in which Donald Trump is playing poker, and Raul Castro is playing dominoes.

Trump, as a businessman, knows that Cuba is a market with exceptional natural conditions, only 90 miles from the U.S., located in the heart of the Caribbean, with highly trained human resources and politically a gateway to Latin America. Making predictions about what Trump’s policy toward Cuba will be is a big risk, his unpredictable style and aggressive negotiating tactics inject a great deal of uncertainty into the future of the U.S.-Cuba thaw. However, there is much at stake. It is a strategic issue, as currently the relationship between the two countries moves a market of $9 billion on both sides of the Florida Straits, in remittances, telecommunications, travel, tourism and food and medicine sales. More than 65 percent of this is on the U.S. side, a fact that Cuban official statistics do not reflect. So I wonder, if Trump wants a solid relationship with Russia, why not with Cuba? Everyone can take their own view.