The ancient Silk Road has many positive connotations in the German popular imagination. Yet Beijing’s plans to create a modern-day variation of the famous route have triggered mixed reactions from China’s largest European trading partner.

Many German trading hubs expect new business opportunities from expanding links with the sea and land routes of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For example, Germany’s largest port in Hamburg, as well as DuisPort, the company operating Germany’s biggest inland port in Duisburg, have expressed interest in becoming “BRI hubs” to attract greater volumes of East Asian and global maritime trade. However, the port of Hamburg is reportedly also developing strategies for coping with expected heavier competition from a range of Southern European ports, which China seeks to establish as maritime gateways for BRI.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel has welcomed the initiative as a means to secure more Chinese investments in Europe and its wider neighborhood. However, Berlin is also concerned about the initiative’s potential to dilute European Union (EU) investment rules and to erode political unity among member states vying for Chinese investment. Moreover, German media coverage has been mostly negative, with press reports depicting BRI either as a geopolitical threat or as an over-ambitious endeavor doomed for failure.

In light of prevailing uncertainties about the geopolitical implications and economic sustainability of BRI, the German government has become active in trying to coordinate Europe’s response to and its involvement with the initiative through the EU, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), or the G20. Berlin is in a good position to play this role – not only due to its status as Europe’s biggest economy, but also due to the fact that, unlike some countries in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe, its economic fortunes do not depend on attracting Chinese investments into its infrastructure.

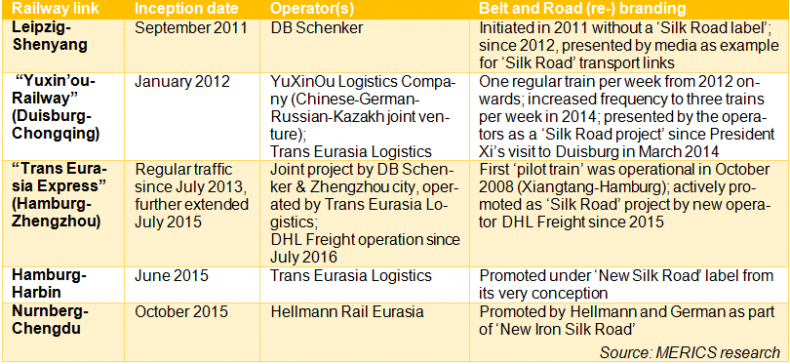

So far at least, Germany’s exposure to BRI projects has been limited to five projects linking existing railroads (see table below). Several of these projects had been planned long before China’s President Xi Jinping launched the initiative in 2013 and were later rebranded as parts of the BRI initiative. Their success over the past year, which saw increased demand for rail cargo transport options between Germany and China, especially in the automobile industry, led to the announcement of follow-on BRI projects. In March 2016, for example, Germany’s state-owned railway Deutsche Bahn (DB) and China Railways signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on further developing the “Eurasian landbridge.”

Apart from this, BRI has neither yielded infrastructure investments nor has it featured as a visible driver of Chinese M&A and greenfield investment activities in the Federal Republic. This is quite different for countries at Europe’s periphery in the east and the south, who are eager to attract Chinese funding to upgrade their infrastructure. They deal with China directly or have joined sub-regional cooperation formats such as the 16+1 group, which brings together 16 Central and Eastern European countries and China on a regular basis to discuss investment projects and the wider political agenda. What is still lacking is an ambitious, constructive, and forward-looking European agenda on how to engage with BRI – which is why the German government has taken the approach of “multilateralizing” the issue.

In Brussels, Germany advocates using the EU-China Connectivity Platform to ensure the conformity of Chinese BRI-related investments in Europe with EU rules and standards. German officials also see this platform as a tool to co-design the new European-Chinese economic corridors. Germany has also supported the work of a new internal working group of the European External Action Service aimed at developing a European vision on Eurasian connectivity beyond mere infrastructure projects. Germany supports the European Investment Bank’s efforts to provide technical support to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and to co-fund AIIB projects related to BRI. Germany’s decision to assume a high profile in the AIIB, which was founded on China’s initiative, constitutes an important indirect attempt to actively shape China’s BRI-related activities in Eurasia.

Germany has also sought to increase opportunities for dialogue and cooperation with China. On the multilateral level, Berlin used its 2016 chairmanship of the OSCE to promote discussions about how to most effectively link up existing and emerging Eurasian connectivity efforts with BRI. In May 2016, the Foreign Office hosted an OSCE conference in Berlin on the topic, which attracted high-level delegations from all 57 OSCE participating states as well from China. Germany managed to lock in Eurasian connectivity cooperation with China on the OSCE’s agenda for the next few years, with another major event with Chinese participation already tentatively scheduled for 2017 in Kazakhstan under the Austrian OSCE Chairmanship. Taking over the G20 presidency from China in 2017, Berlin is also interested in marrying core elements of China’s BRI strategy with German development policy through launching the “Chinese-German G20 Cooperation for Sustainable Infrastructure Investment.”

The Foreign Office and other government agencies have also increasingly sought bilateral dialogue with Beijing. For instance, several high-ranking German Foreign Office officials used a Core Group Meeting of the Munich Security Conference in Beijing in November 2016 to discuss the economic and geopolitical implications of BRI with senior Chinese officials. Besides such dialogues there are also first examples of bilateral cooperation between Germany and China in Central Asia. At the fourth German-Chinese intergovernmental consultations in Beijing on June 13, 2016, Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier signed an MoU on Trilateral Cooperation in Afghanistan. Germany and China plan joint projects to support the country in the areas of infrastructure, energy, transport, environmental protection, agriculture, and health.

Germany’s approach to BRI over the next few years will continue to be primarily defined by concerns about the geopolitical implications of BRI and endeavors to ensure the economic sustainability of China’s ambitious initiative in Eurasia. It remains to be seen if Germany’s endeavors will be received favorably in Beijing.

Jan Gaspers is Head of the European China Policy Unit at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Based in Berlin, MERICS is the largest European think tank concerned with analyzing contemporary China and European China policy.