The recent surge of violence in Afghanistan has renewed fears of widespread public protest in the country. Last week’s devastating terrorist attack in Kabul killed at least 150 people and injured more than 300, leaving it the country’s deadliest attack on civilians since the 2001 U.S. invasion.

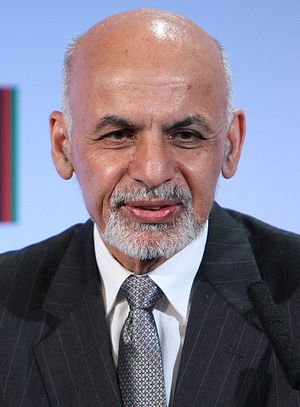

Just days after the Kabul attack, Afghanistan hosted an international peace conference, called the Kabul process, to explore ways to restore peace in the country. While the conference, like numerous other conferences, is unlikely to produce quick measurable results, the venue saw Afghan President Ashraf Ghani emphasize the need to formulate a collective regional security plan.

Moreover, while addressing the conference, Ghani singled out Pakistan for allegedly supporting insurgent groups in Afghanistan which, he believed, had undermined the country’s security and stability. More specifically, the allegations on Afghanistan’s part were aimed at Pakistan’s military and its alleged support for the Afghan Taliban. Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership rejected Kabul’s allegations, say that they were just “baseless” propaganda.

Pakistan’s foreign office said in a statement that “The onus of setbacks and failures in Afghanistan should not be blamed on Pakistan. Mere rhetoric of blaming others to hide their failures in Afghanistan will not solve the problem.” In a separate response, the military in Pakistan said that “instead of blaming Pakistan, Afghanistan needs to look inward and identify the real issues.”

While bilateral relations between Kabul and Istanbul remain hostile, the rapidly worsening security situation in Afghanistan and growing rifts within Ghani’s government may force the current Afghan leadership into reaching out to Islamabad for support.

In his speech at the peace conference last week, while Ghani criticized Pakistan, he also highlighted the its “legitimate interests” in Afghanistan and Kabul’s willingness to address Islamabad’s concerns. “We recognize that Pakistan has legitimate regional security interests and we have offered the appropriate guarantees of neutrality,” Ghani said. Clearly, the statement was aimed at dispelling Islamabad’s anxieties regarding India’s overwhelming influence in Afghanistan, which has primarily been the driving force when it comes to Pakistan’s policy formulations towards Afghanistan.

When Ghani came into office, he tried a policy of reconciliation with Pakistan, which didn’t produce any results as far as the country’s militancy problem is concerned. A number of political stakeholders in Afghanistan that don’t favor reconciliation with Pakistan due to its questionable policies towards Kabul forced Ghani into taking a hard-line approach towards Islamabad. As a consequence, the last year in Pakistan-Afghanistan bilateral dealings have seen both countries mutually accuse each other of being tied up with insurgent groups. Not more than a month ago, Ghani denied Pakistan’s top civilian and military leadership’s request to visit Afghanistan.

Ghani’s latest attempt to reach out to Pakistan has happened because of the very reason that previously became the cause of fallout between the current Afghan government and Islamabad. The recent wave of suicide bombings and growing public discontent has isolated president Ghani to an extent that he has no other way but to seek help from Pakistan.

While speaking at the event, Ghani said that “I would be remiss to my people if I did not say that our top priority must go to finding an effective way to dialogue with Pakistan.” Ghani’s policy of hostility towards Islamabad has not achieved anything besides temporarily warding off the political pressure at home. Arguably, the Afghan’s government’s policy of non-reconciliation towards Pakistan has even failed to achieve the basic objective of securing domestic support for the government: while rifts within Ghani’s government are deepening, the recent violence has provoked widespread unrest, with protesters camping out in the capital. If suicide bombings continue to take place, which appears very likely, the Afghan government’s political isolation will further deepen, which doesn’t bode well for the Ghani’s regime survival.

On the other hand, it’s in Pakistan’s interest that Ghani doesn’t lose control of his government, which may allow other anti-Pakistan stakeholders more political space in Kabul. Previously, Pakistan’s response to Ghani’s overtures was criticized for failing to bring any substantial change in the Afghan Taliban’s policy or demands. Now, however, if Pakistan can deliver to the extent of reducing the scale of violence in Afghanistan, it should be considered nothing less than a clear achievement. With an improved security situation at home while Pakistan doesn’t seem under pressure to comply with Ghani’s indirect requests for help, any improvement in Afghanistan’s security situation can establish Pakistan’s position of being a vital player in the Afghan peace process.

Undoubtedly, further delays in putting together a unified regional policy to secure peace in the country will prove detrimental to any eventual efforts at the regional or national level in this regard. This can simply happen due to the ascendance of the Islamic State (ISIS) in Afghanistan, which is only going to add to the country’s ongoing militancy challenge.

If the government in Afghanistan is looking for an ally in Pakistan, then Islamabad needs to respond positively rather than undermining an already isolated president, which will not serve Pakistan’s interests in any way.