On August 3, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe executed the most important cabinet reshuffle of his tenure, which will not only make or break his chances for extending his time as leader of Japan beyond 2018, but yields valuable insight into the near-term Japanese political landscape. While the possibility of a potential cabinet reshuffle during this summer has been floating around in the media since May, the reshuffle became a must-execute option for Abe, whose public approval ratings were falling fast amidst scandal, cabinet resignations, and other high profile issues. On the retreat, Abe had few options for this reshuffle — he would have to placate potential rivals within his own Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) while seeking ways to shore up his own position as premier in the public eye.

In many ways, this reshuffle could have shown waning resolve from the prime minister, but on the contrary, Abe’s picks, though cautious, did not give too much ground. While there remain some important questions left to answer, this cabinet reshuffle showed that this administration still has a lot of fight left in it and that Abe still has his eyes set on key policy objectives through 2018 and beyond.

Setting for This Reshuffle

The last cabinet reshuffle saw Abe stack the deck with members from his home Hosoda faction and other ideological allies from the party. That Cabinet did not work out for Abe, however. His justice minister (Katsutoshi Kaneda) mishandled the passage of the Anti-Conspiracy Law in the Diet, being unable to explain the details of the bill adequately in Diet interpellations and drawing unnecessary scrutiny. Abe’s original Reconstruction Minister Masahiro Imamura had to step down for repeated gaffes in press conferences. Defense Minister and protégé Tomomi Inada tried to weather the storm surrounding several of her missteps so she could make it to the reshuffle without resigning but failed to do so, leaving her post with less than a week to go. All of this coincided with Abe’s own woes associated with two prominent scandals (the Moritomo and Kake school scandals).

Those missteps afforded space for LDP rivals to accelerate posturing for post-Abe party leadership. When Abe entered 2017 with historically high approval ratings (greater than 50 percent across most polls) it seemed unthinkable that he would depart any sooner than 2020, but rapidly falling public opinion opened the door for some in the LDP to accelerate their timelines, with eyes on the next party presidential election in September 2018. Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso formally merged his faction with the Santo Faction and Tanigaki Group, making it the second largest in the LDP behind Abe’s Hosoda Faction. LDP powerhouse Shigeru Ishiba stepped up his media engagements, openly voicing his criticism of the Abe administration. All of this made for a relatively hostile political environment heading into this latest cabinet reshuffle.

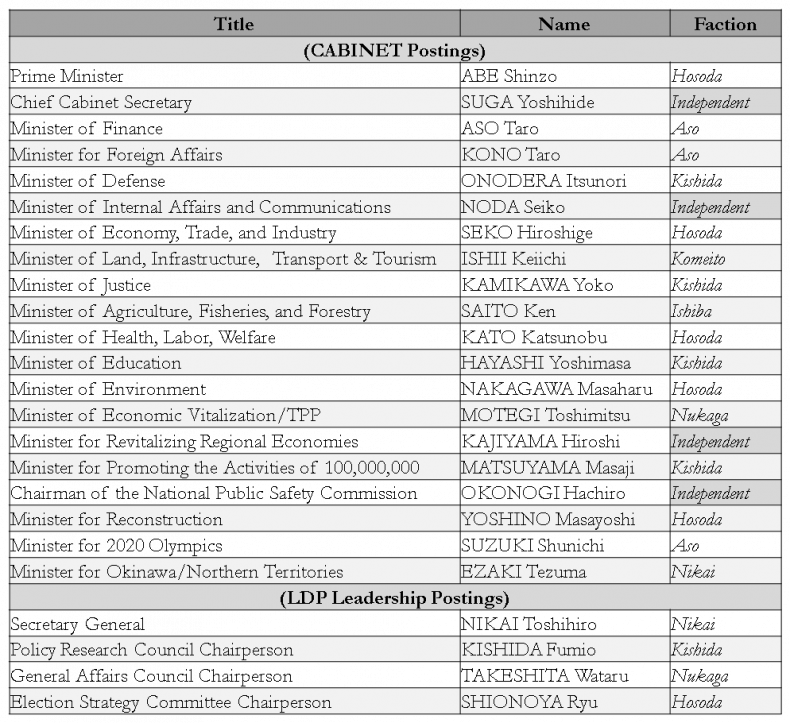

While Abe would have liked to have timed the cabinet reshuffle for a point when he was in full control of the situation, he was in retreat and needed intervention. In this cabinet reshuffle (like others) there were a total of 23 top-tier positions up for consideration, as well as the state/vice minister postings that will be announced later. Which factions would be favored? Would rivals seek to leave the Cabinet to isolate themselves from Abe? Would Abe be able to right his ship using this reshuffle? Those and other questions circled in the media ahead of the August 3 announcements.

The Result

The following table shows the major postings announced on August 3.

While plenty of moves happened during this cabinet reshuffle, some of the biggest names stayed put. As expected, Deputy Prime Minister/Finance Minister Taro Aso remained in his post, as did Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga and LDP Secretary General Toshihiro Nikai.

Of the 23 top-tier posts up for grabs, there were 18 moves; however, unlike the past few reshuffles, this time Abe focused on relying upon the skill of veteran parliamentarians rather than building the portfolios of newcomers to the cabinet. In one way, his aim was to rekindle some of the magic from earlier in his tenure as prime minister, as six members are returning from various postings in earlier Abe cabinets. Meanwhile, Abe was also looking to bring in steady hands who would avoid missteps or gaffes–storms his administration cannot weather at this time. Of those changes, some of the more notable moves are detailed below:

Foreign Minister: Taro Kono replaces Fumio Kishida

After earning the title as longest serving postwar Foreign Minister, Fumio Kishida steps out of his position to move over to a LDP party leadership role. In his place moves Taro Kono, a favorite among many in U.S. policy circles. Son of former LDP powerhouse Yohei Kono, Taro Kono brings a mix of old school LDP lineage with international experience and appeal to the foreign minister position. He is also one of the more outspoken members of the LDP, though his actual ability to influence the Abe administration’s foreign policy decisions remains to be seen.

Defense Minister: Itsunori Onodera fills vacancy left by Tomomi Inada

The shuffling out of Defense Minister Tomomi Inada has been a foregone conclusion for some time now. Among other mistakes, Inada’s ties to the Moritomo Gakuen scandal, her involvement in the alleged cover-up of reports from the Self-Defense Force’s mission in South Sudan, and her use of her position as defense minister in supporting LDP candidates in the July Tokyo Assembly elections sealed her fate. Replacing her is Itsunori Onodera, a practical choice. Onodera served as defense minister under Abe from 2012 to 2014 but has stayed active on defense matters even after leaving his post. He provides security policy continuity for Abe and a reliable figure in a high profile billet given increasing tensions in the region.

Education Minister: Yoshimasa Hayashi replaces Hirokazu Matsuno

For the first time since taking over as prime minister in 2012, Abe relinquished the Education Minister post over to a representative from another faction. Education has long been a policy focus for Abe, so it made sense that he would insert members whom he could easily influence from his own faction and inner circle. Still, by bringing in Yoshimasa Hayashi (a member of Kishida’s faction), Abe invites a steady hand to the ministry that has given his administration the greatest grief as of late — after all, it is the former administrative vice minister of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology who has fueled the Kake and Moritomo school scandals. Hayashi is an able politician who has held several high profile ministerial posts in the past, including minister of defense and minister of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries (MAFF). This also is not the first time that he was brought in to play the role of fixer for Abe, as he took over the agriculture billet in 2015 when Minister Koya Nishikawa was forced to step down due to scandal.

Minister of Internal Affairs and Communication: Seiko Noda replaces Sanae Takaichi

One stand-out selection that reinforces the notion that Abe is keeping his friends close and enemies closer is the introduction of Seiko Noda to the cabinet, replacing long-time Abe ally Sanae Takaichi. In the 2015 LDP presidential race, Noda was the only LDP member who attempted to run against Abe. Although she did not acquire the requisite number of supporters (only 20 names are required), she still represents the fringe population of the LDP that is willing to challenge Abe’s authority and would certainly do so again in 2018. By co-opting Noda, Abe not only offers a high-profile concession to the lawmaker, but keeps her in his immediate circle. He also may invite her to play the role of spoiler against other factions that seek to upset his plans for a legacy turnover, since she could potentially serve to split the vote against other “anti-Abe” LDP rivals in a party presidential race.

Managing Allies and Rivals

Kishida Faction

The most important person to watch in this reshuffle was Minister for Foreign Affairs turned LDP Policy Research Council Chair Fumio Kishida, the leader of the fourth largest faction and a potential post-Abe prime minister. Although Kishida may be a logical successor to Abe in the eyes of the public, he is not Abe’s first choice since his ideology and brand of politics differ from Abe’s own. It remains to be seen whether or not Abe would gracefully hand over the reins to Kishida rather than to a personal protégé, and this cabinet reshuffle certainly did not offer any more insight into whether it would a peaceful transfer of power between the two.

Abe and Kishida held a two hour, one-on-one meeting on July 20, and this reshuffle highlighted the results of that conference. Kishida’s push for a spot among the LDP leadership ranks signals his intent to begin a run for the LDP presidency, but the secretary general position, which Toshihiro Nikai retained, would have been the position necessary to set Kishida up in time for the 2018 LDP presidential race if that was his intent. The Policy Research Council Chair is notable, but it is not a “kingmaker” position. Also, although Kishida’s faction earned four additional postings in the Cabinet, three of those (Hayashi, Onodera, and Kamikawa) were “fixer” positions — basically concessions to Kishida since previous choices were busts. Further, this time around Kishida’s faction only matched the total number of postings it had back in 2014-15 back when Abe called a snap election and reshuffled the cabinet. In fact, whereas in 2014-15, Abe’s own camp only had one notable posting, here, he retained an equal number to Kishida, so it is difficult to say that this reshuffle gives Kishida any groundbreaking leg-up in a post-Abe party environment.

All told, Kishida did posture himself and his faction well for the long-run, but this was not the defining moment for a Kishida-led post-Abe LDP that perhaps some expected.

Ishiba Faction

As mentioned earlier, one-time Abe ally Shigeru Ishiba has been increasingly outspoken about the administration in recent months, presumably to posture for a potential run at LDP presidency in the future. With this reshuffle, his small faction retains just one posting. Ishiba has always had strong ties to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, so it makes sense that he would want a member of his faction to maintain a foothold there. Ken Saito takes on that role while Ishiba keeps his personal distance from the cabinet and Abe-led LDP. Whether that is a result of Ishiba’s impotence compared to other LDP contenders or Ishiba’s own desire to remain isolated is difficult to say, but one can safely assume that Ishiba will continue to provide a dissenting voice ahead of the 2018 LDP presidential race.

Aso Faction

The push to merge with the Santo Faction and Tanigaki Group to form the second largest faction in the LDP did not result in a greater number of high profile positions for Aso’s faction. Certainly, the ascension of Taro Kono to the foreign minister billet was notable, especially since it puts an Aso-sponsored voice in Abe’s favored National Security Council, but the lack of other activity shows that Aso did not make any significant moves to influence the Abe administration in the near term.

Nikai and Nukaga Factions

This reshuffle also represented the status quo for the Nikai and Nukaga factions, which had already cast their lot in with the Abe administration. Neither faction would be able to distinguish itself from the Abe camp if Abe fails to pull out of his public opinion nosedive, and it is unlikely that the LDP would want to repeat the mistakes of 2007-09 by putting forward the similarly minded Abe, Fukuda, and Aso in rapid succession, only to see them fail equally as rapidly. As such, these factions must bank on Abe being able to regain enough popularity to set the foundation for another predominantly right-leaning prime minister (which is what Nikai or Nukaga would offer) in the post-Abe LDP.

Komeito

The LDP’s junior coalition partner Komeito made it out of this cabinet reshuffle right where they started going into it: one billet. This status quo is informative, however, since the cabinet reshuffle did not reflect any of the concerns voiced in the media about a potential schism between the LDP and Komeito at the central government level based on the outcome of the Komeito’s support for the Tokyo Citizens First Party in the Tokyo Prefectural Assembly elections. Any big change in the coalition relationship at the national level likely would have impacted the reshuffle in some way, but status quo shows that such was not the case.

Outcomes

Although some observers and media outlets suggested that the Abe administration was on the ropes going into this reshuffle due to the various scandals and missteps by his former cabinet ministers, Abe certainly did not make decisions as if he was worried about the scorecards. Instead, he made sound appointments by bringing in veteran lawmakers, trying to rekindle the success of previous cabinets, and not conceding too much to other LDP leaders. In the end, it appears that Abe was able to placate rivals while retaining a respectable number of positions for members of his inner circle. In doing so, he has postured himself well for policymaking until the next scheduled test in the form of the party presidential election.

Of course, there are still questions that remain before labeling this reshuffle a total success. Will the public respond positively to these new cabinet appointments? Will Abe be able to overcome the Moritomo and Kake School Scandals? Will Abe be able to maintain patience and discipline in his management of other LDP leaders in pursuit of remaining agenda items?

If the answer to any of those questions is no, in the best case scenario, Abe will continue to fight against the political current with limited success, and in the worst case, he will be looking at an early exit. However, if all of the answers to those questions is yes, he will likely once again find himself in a position to pursue key policy objectives through 2018 and beyond.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the former Deputy Chief of Government Relations at Headquarters, U.S. Forces, Japan. Prior to that, he served as a Mansfield Fellow, completing placements in Japan’s National Diet, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Defense. Follow him on twitter @MikeBosack.