Nothing annoys me more than being told by foreigners that they are surprised there are mental health problems in such a happy country; even foreign journalists have said this! We have had a successful branding exercise, I will admit, as the “happiest country” in the world because of our development philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH), but that does not mean Bhutanese are insulated against anxiety, depression, and mental disorders.

Anxiety and depression are the most common mental health disorders in Bhutan, according to records maintained at the national referral hospital. The Annual Health Bulletin states there were more than 4,200 cases related to mental and behavioral disorders in 2017. The country is no stranger to suicides either. Suicides have been increasing yearly. It may not be in the thousands like in other countries, but for a population that is barely a million right now, even a hundred suicides is too many. The government has a “suicide incidence reporting system,” which shows that suicides are mainly caused by depression or other mental illnesses.

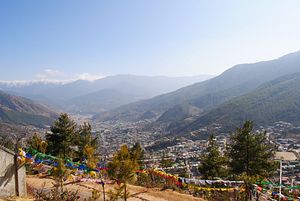

The country has only four psychiatrists to date. There are no psychologists or therapists. Mercifully, there a few trained counselors, but the majority of them are based in the capital, Thimphu. All four psychiatrists are based in the capital, too. At least the budget towards mental health is looking better than it ever has in the past. The Health Ministry has proposed about 60 million rupees ($820,000) over the next five years for mental health interventions like rehabilitation for addiction problems, suicide prevention, research, and capacity development.

Bhutan is in urgent need of mental health services as well as education and awareness on the importance of mental health. Unlike most countries of the world, Bhutan unfortunately faces a rare challenge: language. The national language, Dzongkha, as well as many other dialects spoken in the country cannot describe one’s mental state adequately. We do not have a vocabulary for mental health. This is what the two oldest psychiatrists in the country have shared with me. The practice of psychiatry began only about two decades ago so the challenges are manifold.

Firstly, most Bhutanese associate mental illness with madness, hence any kind of mental ill health is stigmatized. There is barely any national conversation on mental health although psychological well-being is one of the nine domains of GNH. I would know. I have been aggressively advocating for mental healthcare for over two years through social media activism and through the country’s only mental health show on a private radio station.

I have also been working closely with psychiatrists and counselors. A psychiatric consultation is the last thing on the minds of most Bhutanese. The first consultation is almost always with a general physician who in turn will forward the case to a psychiatrist. Most patients are almost always indignant and very much in denial when they are told they are suffering from mental ill health. Actually, more often than not, there isn’t even a medical consultation. Bhutanese will take people to traditional healer — some of whom have endangered the lives of many a Bhutanese because they were just quacks. Psychiatrists tell me that there are so many patients who are in a state beyond treatment by the time they finally see them.

The mental health of Bhutan became a cause for concern after the Health Ministry compiled the country’s first preliminary report on suicide in 2014. It was serious enough for the last government to initiate a three-year action plan for suicide prevention in the following year, and now the National Suicide Prevention Programme (NSPP) with the Health Ministry is working on a five-year action plan. The country does not have a suicide prevention hotline, but anyone who answers the emergency hotline #112 is trained to handle mental distress calls round the clock, and health workers around the country have been trained to deal with mental health issues as well. There are certain interventions in place, but so much more needs to be done.

The country needs psychologists and more counselors. Therapy needs to be an alternative since a majority of Bhutanese are afraid of undergoing medicated treatment for mental illnesses. What is also different in Bhutan is that the two oldest psychiatrists have pioneered mental health care and are not averse to Bhutanese seeking the treatment they feel works for them, including religious practices and traditional healers. They tell me that what gives your mind peace will heal you, too.

Mental health advocacy may be new to Bhutan, but a holistic approach to dealing with mental health challenges isn’t. This probably stems from the fact that the country is a Buddhist Kingdom and everyday life is very much influenced by Buddhism – moderation, mindfulness, etc. We have the approach, now we need the motivation. With the right motivation, interventions will be successful in the kingdom and mental health issues can be brought under control sooner than later.