Let Her Fly is the story of a father who stood up against all odds to challenge gender discrimination in a society deeply rooted in patriarchy and male chauvinism.

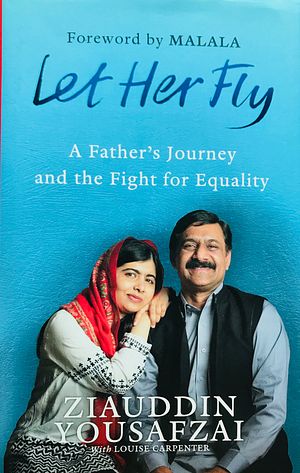

Ziauddin Yousafzai, father of Nobel laureate and girls’ education activist Malala Yousafzai, subtitles the book “a father’s journey and the fight for equality.” Co-authored with Louise Carpenter, Let Her Fly recounts Ziauddin’s journey from his small village in Shangla district to becoming a global figure.

Long before the birth of his “blessed child,” Ziauddin was sensitive to the discriminatory behavior by his parents toward his five sisters in terms of food, clothing, and education as compared to him and his brother.

However, his real struggle began with the birth of Malala, when his father refused to celebrate the girl child. Next came the question of her education and the family once again saw no reason in educating a girl, who is destined to be a bride and make a family.

The personal struggle for equality, which started for Ziauddin’s family on July 12, 1997, Malala’s birthday, became a movement when Ziauddin, along with his “unwelcomed” child, challenged the ban on girls’ education by the Taliban.

Most families in rural Pakistan see boys as a hope for a better future, both socially and economically. Not only do girls have lower status as compared to boys, but at times they are given away to settle blood feuds and family loans.

“When I say of Malala ‘I did not clip her wings,’ what I mean is that when she was small, I broke the scissors used by the society to clip girls’ wings. I did not let those scissors near Malala. I wanted to let her fly high in the sky, not scratch around in a dusty courtyard, grounded by social norms,” Ziauddin writes in his 169-page personal memoir.

He abhors the norms that restrict girls’ education and discriminate against them in the family and society. “I do believe that social norms are like shackles that enslave us. We are content in the slavery, and then when we break the shackles, the first feeling of liberation might be shocking at first, but as we begin to feel the freedom we sense in our souls how rewarding it is.”

Ziauddin’s silent struggle entered a new and dangerous stage when the Taliban took over most parts of Swat, the serene valley in Pakistan’s northwest also known as the Switzerland of Asia.

The Taliban aired threatening sermons from their illegal FM radio station warning that “wrong-doers,” including parents sending girl children to schools, had become a new normal in the valley.

Ziauddin did not back down. Instead, he redoubled his efforts by bringing forward his 10-year-old daughter to challenge the Taliban ban on girls’ education. Around that time, I saw little Malala reciting a poem during a gathering in the Peshawar Press Club.

A father’s struggle against social norms, gender discrimination, and patriarchy became the struggle of both father and daughter against a more serious threat: The Taliban and their antagonism to girls’ education.

Detractors still question Ziauddin’s decision to put young Malala in a struggle against violent extremists, but only a man with strong belief in his ideals can take such a risk.

He loved his ideals, his family, and his cause and when he saw the Taliban violently taking over Swat and banning girls from schools, he could not hold back. “I would stand on the bank of River Swat and would cry: Oh, the world is so beautiful!”

Like many other reporters covering the Talibanization of Swat, I was a witness to Ziauddin’s struggle for peace and girls’ education from the platform of his little-known “Global Peace Council.” I joined him more than once in BBC Pashto language debates on the situation in Swat, where he used to openly challenge the Taliban logic of banning girls’ education.

Ziauddin does call himself “naïve” for disregarding the threat to Malala’s life. But despite all their brutalities, no one was expecting the Taliban to target a teenager, and a girl.

“Malala was shot by the Taliban because of the power of her voice. It had started to make a real difference in Pakistan. It had grown louder and more powerful between 2009 and 2012,” he writes.

Before the attack on Malala, Ziauddin had received death threats from the Taliban in 2008 and 2009, but they did not target him in the end. “By targeting Malala, the Taliban had found a way of silencing me,” he believes.

Ziauddin’s story is incomplete without a mention of his wife, Tor Pekai. While many in the conservative Pashtun society do not mention the names of their female relatives in public and refer to them using their relationships to male family members such as “mother of,” “sister of,” or “daughter of,” Ziauddin proudly calls his wife his best friend.

He wed Tor Pekai in an arranged-cum-love marriage and he openly talks about his love affair within the confines of that conservative rural society.

Tor Pekai told me in an interview that village women used to gossip about her sitting with Ziauddin on the same bed or eating together after their marriage. In rural areas, the wife is not supposed to eat together with her husband or sit on the same bed. Women were also supposed to keep quiet while males discuss family issues. But “I found Ziauddin a different man who gave me the courage to speak in front of our male family members,” she said.

Ziauddin is a feminist who only came to know the meaning of the word “feminism” when he landed along with his family in Britain. But even in London patriarchal norms run deep. Ziauddin recounts a conversation with a cab driver who advises him to never trust three “Ws” in London – work, weather and women. In turn, he advises the driver that it should be two “Ws” and one “M” instead – work, weather and men.

Let Her Fly encompasses the struggle of a father, a husband, and a peace activist against social norms, taboos, and male chauvinism. He feels hurt when people, mostly his countrymen, taunt him for bringing forward his daughter. But he does not care. “I am one of the few fathers of the world who is known by a known daughter,” Ziauddin told me in a recent conversation.

Now that Malala is no longer a child, Ziauddin draws inspiration from her strength. He feels proud when Malala proclaims that she does not want to be known as the girl shot by the Taliban, but rather “the girl who fought against the Taliban.”

He also feels proud that his daughter strongly believes in women’s ability to change the world. Ziauddin remembers that Malala changed one well-known Tapa, a Pashto folk poem. The original Tapa says: “If the men failed to win you honor, O my country, then the women will do that.” But Malala, after surviving a would-be assassin’s bullet, created a new version: “irrespective of the men winning or losing, O my country, the women will definitely win you honor.”

In his memoir, Ziauddin takes the readers to his small, impoverished village in the mountainous and remote Shangla district in Pakistan’s northwest. The inclusion of minute details about his village and family life in Shangla shows his deepest love for his land.

“I would not waste a moment going back to my country and start helping my people the day I come to know there is no threat to the lives of my family members,” Ziauddin pledges.

While Let Her Fly is an effort by Ziauddin Yousafzai to tell the world about the life and hardships of a father in that conservative part of Pakistan, it is also an endeavor by a father to tell his countrymen that educating and allowing freedom to girl children does not bring shame. “Trust your daughters as much as you trust your sons and they will not disappoint you,” he advises.

This personal memoir of the man behind a daughter as brave as Malala Yousafzai carries a strong message for parents in Pakistan and Afghanistan: trust the abilities of their girl children by letting them fly instead of clipping their wings.

Daud Khattak is Senior Editor for Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty’s Pashto language Mashaal Radio. Before joining RFE/RL, Khattak worked for The News International and London’s Sunday Times in Peshawar, Pakistan. He has also worked for Pajhwok Afghan News in Kabul. The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not represent those of RFE/RL.