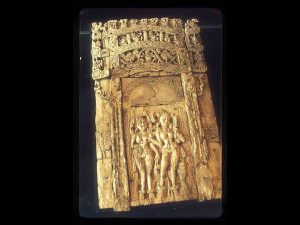

In 1995, a cache of antiquities sourced by a mujahideen commander made its way to the international art market through Afghanistan’s porous border with Pakistan. Two decades later, the artifacts were discovered in a Manhattan dealer’s warehouse during a sting operation to uncover an extensive antiquities trafficking network. In April, the Buddhist, Hindu, and Greek relics were shipped to the National Museum in Kabul, one of several art homecomings that have taken place in recent years. Other repatriated items include artifacts from the Begram Ivories and a rare Ghazni panel.

But with Kabul falling to the Taliban, the fate of the National Museum’s world-class collection hangs in the balance. The Islamic insurgents’ contempt for representational art is well known. In March 2001, they shocked the world by blasting the Buddhas of Bamiyan with explosives. The sandstone statues, considered blasphemous because they represent the human form, were destroyed on the direct orders of Mullah Omar, the founder of the Taliban.

The National Museum was another target of the iconoclastic purge. In February 2001, Taliban fighters went on a rampage at the grey cement building, smashing more than 2,500 artifacts with hammers and axes. Risking their lives, museum staff picked up fragments and hid them in the trash or safe rooms. The Taliban attack came soon after a harrowing patch in the museum’s history when the building was attacked by rockets, looted, and even used as a military base during the civil war.

Despite the setbacks, the museum reopened in 2004, and the staff began the painstaking work of reassembling the shattered fragments, working with conservators from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. One of the restored pieces was a statue of Kanishka, the second-century emperor who presided over the spread of Buddhism across Asia. By 2019, the museum’s once-depleted collection was expanding again. British authorities handed over a trove of 843 artifacts, seized two decades earlier at Heathrow airport, completing one of the largest repatriations of Buddhist art to Afghanistan.

In August that year, diplomatic talks between the United States and the Taliban were gaining traction in Qatar, and the peace deal that would become the Doha Agreement was in the draft stage. With the return of the Taliban a distinct possibility, Mohammad Fahim Rahimi, the National Museum’s director, made an appeal. He urged the group’s delegation to visit museums in Doha and Qatar to gain a better understanding of pre-Islamic art. “I hope they have learned that this is not against the (law) of Islam, nobody is worshipping these objects,” Rahimi said.

In February, the Taliban released a statement saying they had an “obligation to robustly protect, monitor and preserve” Afghanistan’s heritage and safeguard historic sites from looters. Although the recent fighting has been fierce, there have been no reports of the destruction of artifacts. Employees at some museums and archeological sites outside Kabul have been told to stay at their jobs. The link to the interactive exhibit of Buddhist artifacts repatriated in April remains active on the Afghanistan embassy’s website. However, the Taliban’s statement on protecting historic sites is no longer available.

On the day Kabul fell, the National Museum posted a message on Facebook expressing concern over the deteriorating security conditions in the city but reassuring followers that their 80,000 artifacts were safe. The museum appealed to “influential parties,” including the Taliban, to help prevent looting if the “chaotic situation” deteriorated further. The director told National Geographic: “We have great concerns for the safety of our staff and collections.”

Notably, Afghanistan’s greatest treasure is not at the museum. The Bactrian Hoard, an exquisite collection of jewelry, coins, and figurines, is currently stored in a vault at the central bank. Initially displayed at the museum, the trove of more than 20,000 objects went missing during the civil war years. In 2004, they were rediscovered in an underground safe at the presidential palace, where they had been placed for safekeeping by museum staff. The collection is a financial asset to the economy, earning more than $4.5 million in foreign exchange from exhibitions. In addition, its gold supports the nation’s currency.

In January, the speaker of Afghanistan’s parliament warned that massive outflows of cash had weakened the central bank and the priceless collection was in danger of falling into the wrong hands. But a minister in then-President Ashraf Ghani’s cabinet assured lawmakers the Bactrian gold was “safe and sound.”