Recently, the Taliban’s deputy minister of information and culture made headlines when he asserted that “Afghanistan does not need Persian literature.” Sputnik Afghanistan reported that when addressing a group of graduate students at the Gulghulah Hotel in Bamiyan on August 4, 2023, Deputy Minister Muhammad Yunus said that students should not waste their time learning Persian literature; instead they should learn how to make advanced weapons for warfare.

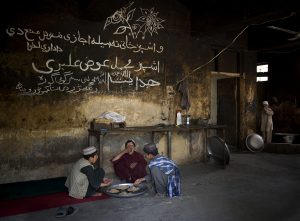

One of the first things that Taliban did after taking over in August 2021 was to remove Persian from public billboards. Shafaqna Afghanistan reported that Taliban officials replaced the trilingual billboard for Balkh University with a bilingual one (Pashto and English), removing the Persian word “Danishgah” from all university banners across the country.

It is important to decode this behavior. The Taliban’s anti-Pesianism is rooted in their educational and cultural background as well as the Afghan government’s longstanding desire to push out Persian. To understand the Taliban’s linguistic politics, then, one has to examine the group’s relations with Pashtun tribalism, the Deobandi madrassas, and the Afghan government’s ethnolinguistic policies in the last century.

Pashtun Tribalism and Deobandi Madrassas

Barakzai Pashtun elites and urban Pashtuns in Afghanistan have either been bilingual or entirely Persian speaking. From Ahmad Shah Durrani to Zahir Shah, the last Barakzai king, these elites have been raised and educated in a Persianate environment, with some hardly able to read in or speak Pashto. However, the masses of Pashtuns in the tribal belts in Afghanistan and Pakistan have not been exposed to Persian cultural influence in the same way. The core groups of the Taliban come from these tribal areas, for whom the Persian language and people represent “otherness.”

According to James D. Templin, writing in 2015, “Most of the top leaders of the Afghan Taliban including Mullah Omar are alumni of Jamia Uloom-ul-Islamia in Binori in Karachi – one of the largest Deobandi [madrassas] in Pakistan.” Furthermore, as Tariq Rahman described in 1998, the language of instruction in Deobandi madrassas differs per region. In the madrassas of Pashto-speaking regions of Pakistan, Pashto is the language of instruction, and Persian literature and language hardly play any role in their curriculum. The textbooks taught in these madrassas are either medieval Arabic textbooks or their Urdu and Pashto translations. The graduates of these madrassas are now dispersed across Afghanistan, without having any knowledge of Persian Islamic literature. Many, therefore, see Persian literature as a threat or even heresy.

Anti-Persianism of the Afghan State

The Taliban are also aware of the language policies adopted by earlier Pashtun elites in Kabul in the last century. For over 100 years, there have been repeated attempts by various governments in Afghanistan to sideline the Persian language in favor of Pashto.

King Aman Allah and Mahmud Tarzi’s efforts to gradually replace Persian with Pashto as the state language failed; however, they inspired successor governments to follow the same path. King Muhammad Nadir and his brothers followed a robust anti-Persian policy. Prime Minister Muhammad Hashim declared Pashto as the only language of state in 1937. Besides obliging government officials to learn Pashto, he made it the language of education, too. In this period, Anjuman-i Adabi-yi Kabul (the Kabul Literary Society), a state-funded institute, and later Riyasat-i Mustaqil-i Matbuʿat (the Independent Press Chairmanship), took on the mission to develop a national terminology based on the Pashto language and produce texts in the Pashto language.

Although this policy was amended in 1946, allowing Persian-speaking people in Persian-majority cities, including Kabul, to conduct schooling in their mother tongue, and reintroducing Persian as another official language of the state, the Pashto-ization of education and politics continued in a more settled way.

The nephew of Prime Minister Hashim Khan, and a true believer in his domestic politics, Prime Minister (later president) Muhammad Daud continued the language policies of his uncle. With the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, and the rise of a Tajik communist, Babrak Karmal, to power in 1979, the scenario changed, and Afghanistan became a bilingual state a true sense. Later, the Tajik-led Mujahideen government in the early 1990s remained Persian-centric, with the national anthem changing from Pashto to Persian for the first time.

The first Taliban government, in 1996, resumed the anti-Persian policies of the 1930s and made efforts to preserve the monopoly of the Pashto language and Pashtuns in politics.

Looking back at this history, the survival of Persian as the language of state and education in Afghanistan has largely depended on the power of pro-Persian urban Pashtuns and Persian-speaking Tajiks. With the return of the Taliban back to power in August 2021, the position of the Persian language was weakened once again. It has also come at the cost of marginalization of the Persian-speaking population and undermining their rights to political participation.

The Convergence of Anti-Persianisms

It is important to note that from the early 1930s to date, the language issue has been employed by the dominant group as an instrument to promote Pashtun-centric national identity and marginalize non-Pashtuns in Afghanistan. The Taliban’s language policies and practices do not deviate from this principle. However, unlike the urban Pashtun elites’ anti-Persianism, which is rooted in their quest for hegemony, the Taliban’s anti-Persianism also has tribal and Deobandi subtexts to it.

While the Pashtun elites were exposed to Persian literature and language in their everyday lives, the Taliban have largely been located outside of the Persian sphere of influence. The Persianate literati in Afghanistan is largely composed of urban Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks, who either speak Persian as their first language or are educated in the Persian language. The Taliban leadership and the masses of the Taliban are not part of this Persianate literati. They have no knowledge of Persian Islamic literature and show no empathy toward Islam practiced by the Persian-speaking masses in Afghanistan.

As a result, the non-tribal part of Pashtun society, as well as non-Pashtuns who were introduced to Islam through Persian Islamic literature, look down upon the Taliban’s Islam as foreign to Afghanistan. The religion of Islam in Afghanistan has been taught by Persianate literati who were aware of the converging point of Persian culture and Islam. With the number of local Persianate madrassas diminishing in Afghanistan, the religious leadership is increasingly de-Persianized and poses a danger to local Islam in Afghanistan. The Taliban government works only with those elements and groups among non-Pashtuns who have a background in Deobandi madrassas and have Pashtunized to some extent.