On November 15, 2022, Indonesian President Joko Widodo and a group of nations led by the United States announced a $20 billion climate finance deal to help Indonesia curb its power sector’s reliance on coal, and transition towards a carbon-free energy system. This deal is officially called the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). A year later, Indonesia released implementation plans for the agreement, outlining numerous targets and policies to help Indonesia achieve carbon neutrality and grow its domestic renewable technology industry. However, none of the recommended policies address the most significant threat to Indonesia’s energy transition: fossil fuel subsidies.

On November 21, 2023, the government of Indonesia released a draft implementation plan outlining its strategy to utilize the support provided by the JETP. The draft implementation plan, formally known as the Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan (CIPP), outlines three primary targets for Indonesia’s electricity system: 1) to cap power sector emissions by 2030 at a level of 250 megatons of CO2; 2) to reach renewable energy generation of 44 percent by 2030; and 3) to achieve net zero emissions in the power sector by 2050.

The CIPP estimates that to reach these targets, Indonesia must attract funding of at least $97.1 billion by 2030 and $500 billion from 2030 to 2050. The $20 billion in financing from the JETP is “expected to serve as a catalyst” to help attract further investment from other sources.

The CIPP outlines five priority areas of investment to focus on through 2030: $19.7 billion covering new transmission lines and grid upgrades; $2.4 billion to retire or retrofit coal plants; $49.2 billion to build 16.1 GW of dispatchable renewable capacity (bioenergy, geothermal, and hydropower); $25.7 billion to build 40.4 GW of variable renewable capacity (solar and wind); and an unspecified amount to improve Indonesia’s renewable energy supply chain, particularly solar PV manufacturing. Indonesia’s continued use of fossil fuel and electricity subsidies threatens these goals.

Indonesia’s government provides generous fuel and electricity subsidies to support poorer households and spur economic development by keeping prices low. These subsidies started under the Suharto regime (1966-1998) when Indonesia still had significant domestic oil reserves. However, since the 1990s, Indonesia’s domestic oil production has fallen while demand for oil and electricity has skyrocketed.

As a result, energy subsidies have reached up to 2 percent of Indonesia’s total GDP. Furthermore, these subsidies primarily benefit wealthier Indonesians. The World Bank notes that Indonesia’s middle and upper class “consume between 42 and 73 percent of subsidized diesel.”

Currently, the following subsidies and price caps are in place. This list does not outline all government market interventions but includes those that could negatively impact Indonesia’s energy transition.

First, Indonesia maintains a subsidy for gasoline and diesel. In 2022, the Indonesian government raised the price of subsidized gasoline and diesel, but the cost of these goods is still below market rates for Indonesian consumers. Usually, these subsidies come as reimbursements to Pertamina, Indonesia’s state-owned oil and gas company. Pertamina owns most of the gas stations in Indonesia. Indonesia’s central government compensates Pertamina for the difference between the cost of purchasing oil and gas and the final price consumers pay.

Second, a domestic sales mandate and coal price cap force Indonesian coal mining companies to sell 25 percent of their coal to PLN, Indonesia’s state electricity utility. Similar mandates exist for oil and natural gas, though those two fossil fuels comprise a much smaller portion of total energy generation than coal.

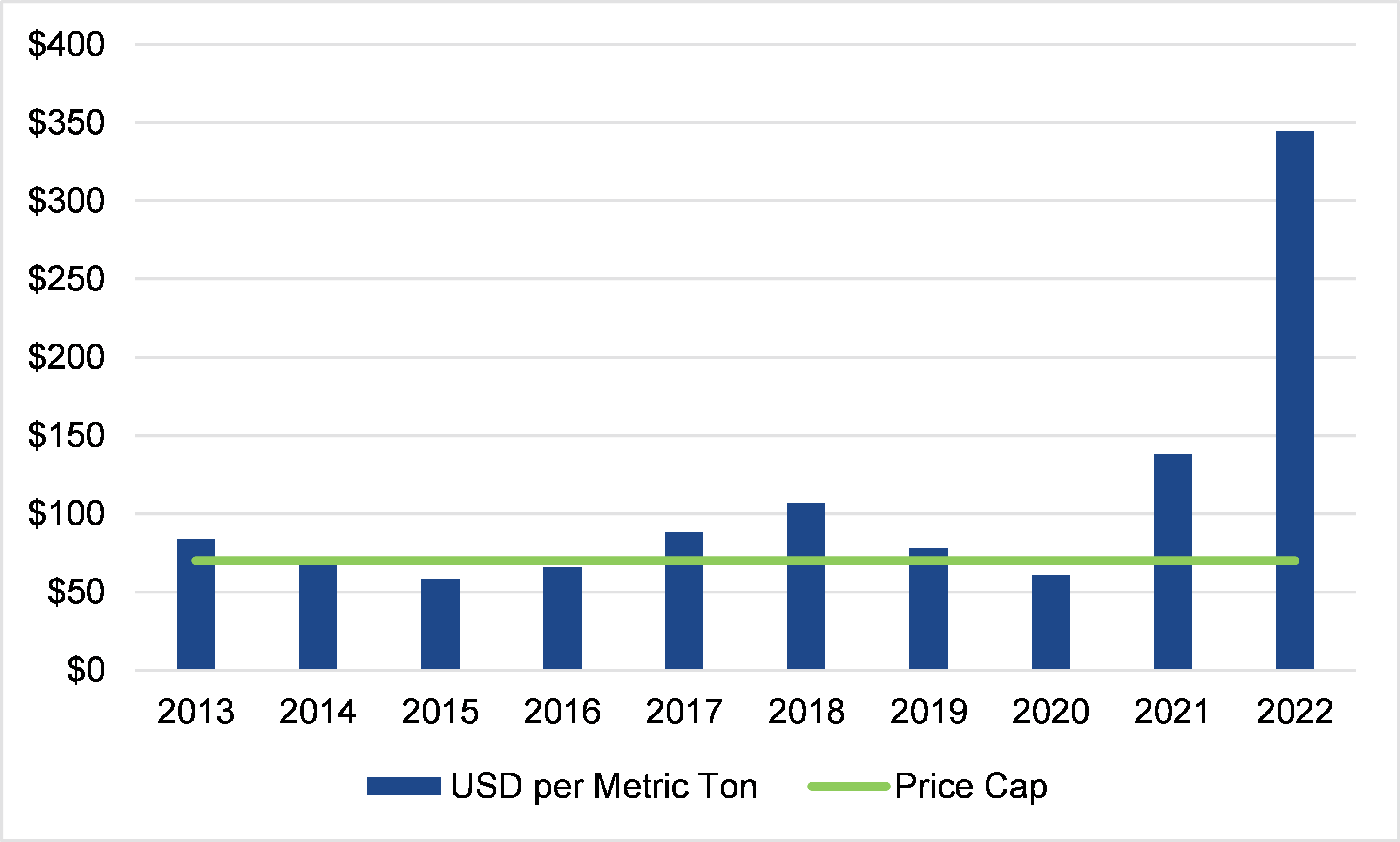

These coal producers cannot sell coal to PLN for more than $70 per metric ton. Figure 1 below compares coal’s yearly average market price against the $70 price cap. In every year but three, the market price exceeded the price cap, and in 2021 and 2022, the market price was significantly higher than the price cap. The sales mandate and price cap artificially lower PLN’s cost of generating electricity with coal power plants, which helps keep electricity costs for end-users low.

Figure 1: Price of thermal coal vs. $70 domestic price cap.

Third, a below-market tariff structure ensures that Indonesian consumers pay less than the cost of generating and distributing electricity. The Indonesian government compensates PLN on an annual basis for this shortfall. Until 2012, all electricity customers benefitted from this below-market tariff structure, but the government removed tariff support for wealthier segments of society in that year.

The “policy enablers” outlined in the CIPP do not sufficiently alter Indonesia’s subsidy regime. Instead, the policies Indonesia’s government outlines in the CIPP simply attempt to address the anti-competitive effects of these subsidies. This is a significant weakness, as much of the funding for new renewable generation must come from the private sector. Few private sector companies will invest in renewable energy projects in a non-competitive market.

One enabling policy outlined in the CIPP is titled “supply-side incentives” and focuses on methods of reducing domestic support for the coal industry. The CIPP outlines Indonesia’s domestic market obligation, which requires coal producers to sell 25 percent of their total production to the domestic market for no more than $70 per metric ton.

These subsidies impact PLN’s electricity planning decisions. Because PLN can access a guaranteed coal supply at a low price, coal-fired electricity is significantly less expensive than other sources, such as renewables or natural gas. As a result, PLN is more likely to build coal-fired power plants or sign contracts with independent coal plants. These policies do not incentivize PLN to decarbonize or engage with renewable energy developers.

The CIPP recommends removing the domestic price cap of $70 per metric ton while maintaining the 25 percent domestic market obligation. As this could increase PLN’s costs of purchasing coal, the CIPP recommends collecting charges from mining companies to help pay PLN’s higher costs (the Indonesian government pays PLN for the difference between the cost of producing electricity and the final rate charged to customers). However, the CIPP notes that Indonesia’s government is formulating different reforms that would not remove the domestic market obligation or the price ceiling.

If Indonesia implements the CIPP’s recommendation, PLN will use “a coal price that is closer to market prices in its dispatch and investment decisions.” However, “closer” may not change PLN’s investment or dispatch decisions. If PLN can access coal or coal-fired power at below-market prices, renewable developers will be hard-pressed to compete, limiting investment and undercutting Indonesia’s energy transition.

A second enabling policy outlined in the CIPP focuses on power purchase agreements (PPAs). A power purchase agreement is a contract between a power producer (such as a power plant owner) and an off-taker (usually a utility). In Indonesia, PLN is the lone off-taker; thus, signing a PPA with PLN is necessary to attract funding and develop a new renewable energy project. The Indonesian government dictates the structure of these contracts. The CIPP outlines recommendations to improve Indonesia’s PPA framework, including standardizing PPA templates to make negotiations easier and developing regulations to more clearly allocate risk between PPA signatories. However, these measures are not enough to make renewables competitive with coal.

Renewable PPAs in Indonesia are subject to a tariff ceiling, a cap on the price they can sell electricity to PLN. Indonesian law requires PLN to ensure that signing a new renewable energy PPA does not increase customers’ electricity prices. As a result, the price of energy produced at a solar or wind farm “should be equal to or lower than the cost of supplying electricity generated by subsidized fossil [fuels].” As long as PLN’s can purchase subsidized coal, renewables will not be competitive in Indonesia.

The most apparent result of continued fossil fuel subsidies in Indonesia is a continued dependence on fossil fuels. A more insidious result is the stagnation of Indonesia’s green technology supply chain. If these subsidies continue, Indonesia could miss out on an opportunity to become a renewable energy powerhouse despite the funding made available under the JETP.

Given Indonesia’s rapidly expanding nickel mining capacity, the country will provide a large portion of the precious metals needed to build electric vehicles, long-term battery storage systems, and other renewable technologies. The CIPP outlines “renewable energy supply chain enhancement” as the fifth primary area of investment through 2030, alongside more tangible efforts to build new renewable energy capacity. Building a robust renewable energy supply chain in Indonesia would strengthen its position globally, allowing it to develop and export more complex products than newly mined nickel alone.

However, the CIPP also identifies “cultivating a sustainable, long-term domestic market” as a significant challenge. Coal price caps will prevent investors from building renewable generation facilities. Without renewable facility construction in Indonesia, there will be no domestic demand for Indonesian solar or battery manufacturers. Similarly, petroleum subsidies will prevent Indonesian consumers from seeking electric vehicles as gas vehicles will continue to be cheaper. Only by dismantling these subsidies can Indonesia use the JETP to decarbonize its energy system and become a leader in the global energy transition.