There’s a melancholy quality to ships whose passing signals the end of an age. Think about J. M. W. Turner’s painting of The Fighting Temeraire—the pride of the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars—being towed away to a shipbreaker by a lowly, unglamorous steamer. Or there’s the Titanic—an oceanliner jokingly dubbed “the world’s largest metaphor”—which ran afoul of a North Atlantic iceberg in 1912. The Titanic disaster brought the Victorian epoch to an end on the eve of World War I.

And then there’s the Yamato, the Imperial Japanese Navy dreadnought that by many measures represented the zenith of battleship design. Few will shed a tear for the Japanese Empire’s downfall. Some might regret the unseemly manner of the Yamato’s destruction, though not the final outcome. Like the majestic Temeraire, the Yamato and her sister battlewagon, the Musashi, met their fate at the hands of lesser craft. Destroyers, or “tin cans,” sank the Musashi at the Battle of the Subuyan Sea, during the Leyte Gulf campaign of 1944,while compelling the Yamato to retire from the only surface engagement of its brief life. Its crew subsequently undertook a suicide mission to Okinawa. Torpedoes,not punches and counterpunches from heavy-caliber guns, decided these epic encounters. Such a doom surely merits an elegy.

Certain facets of the Yamato’s career echo in today’s Western Pacific strategic competition. First, Japanese shipwrights managed to construct the Yamato-class behemoths in extraordinary secrecy, hiding their dimensions and technical specifications from prying eyes. Concealment was particularly challenging in the case of the Musashi, which was built in Nagasaki—within view of the American consulate. Similarly, Chinese shipyards have sprung repeated surprises on Western observers, unveiling new-design submarines, destroyers, and other craft only when they were nearing completion.

Second, Western naval intelligence services did a poor job appraising the superbattleships, in part because analysts simply couldn’t fathom that an Asian people like the Japanese could pull off such a technical feat. (See Torpedo, Long Lance.) They wore blinkers—much as many Western observers denigrated China’s maritime exploits until they became undeniable. Small wonder the PLA Navy has defied expectations.

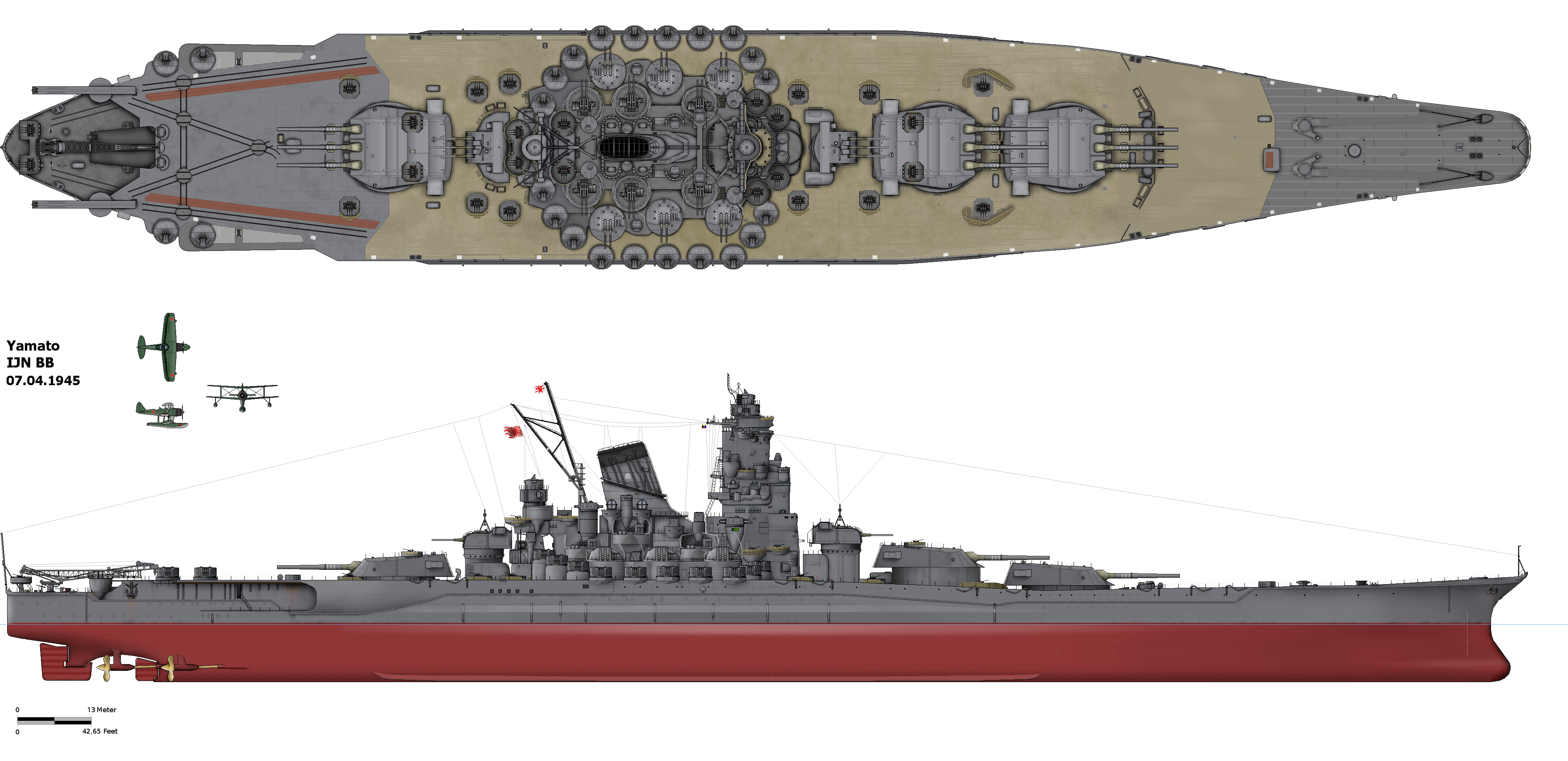

Third, the Imperial Japanese Navy wanted the Yamato class to outmatch enemy capital ships in every respect, trusting to quality to offset superior U.S. Navy numbers. Accordingly, designers outfitted the ships with the heaviest main battery afloat, 18.1-inch guns capable of flinging 3,200-lb. shells about 23 nautical miles. (For comparison’s sake, the U.S. Navy’s Iowa class, the summit of American dreadnought-building, boasted 16-inch guns that could loft 1,900- or 2,700-lb. projectiles around 20 nautical miles.) They also encased the engineering plant, ammunition magazines, and other vital areas of the Yamatos in thick armor plate. These were impressive accomplishments by any standard.

Nor should Tokyo’s efforts be reduced to hubris or folly. The Yamatos were equal to the challenges for which they were designed. During the interwar years, orthodox opinion held that gunfire and bombs were the arbiters of high-seas combat. With heavily shielded machinery spaces and gun turrets, with 27-knot speed, and with the heaviest armament afloat, the superbattleships were up to foreseeable challenges. Yet necessity is the mother of invention. Naval technology—chiefly naval aviation and torpedoes—spurted ahead during World War II, empowering the battleships’ deadly new enemies.

It’s worth pondering whether exotic technology—antiship ballistic missiles, electromagnetic railguns, high-energy lasers—will overtake today’s state of the art in similar fashion. Temeraire, Titanic, Yamato—history suggests the last word on naval technology hasn’t been uttered yet.

From our Naval Diplomat: Several eagle-eyed readers rightly point out that the Musashi fell to air assault, not destroyers. My apologies for the fumble fingers. The larger point is that the superbattleships succumbed to "lesser" implements of war, meeting their doom under circumstances radically different from any their designers could have foreseen. That point stands.