If a picture is worth a thousand words, what’s a metaphor worth? A lot. If, that is, it’s aptly chosen, if folks use it precisely, and if it’s not so overused that it loses all meaning. Alas, big institutions — governments, armed forces, firms — have a bad habit. If a senior leader utters a slogan or acronym, subordinates — team players all — tend to repeat it so often and so casually that it ends up saying little. Today’s metaphor of the day: “spreading the theater” in Asia. Over at Breaking Defense, Sydney Freedberg reports that Admiral Samuel Locklear, grand poobah of the U.S. Pacific Command, has taken to using this metaphor to describe U.S. strategy in East Asia and the Indian Ocean region. Before it becomes common parlance, it’s worth asking what a football reference like spreading the theater means in a naval and military context.

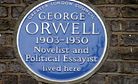

And for biting commentary on questions of language, who better to ask than George Orwell? Orwell warns against using any simile or metaphor commonly seen in print. He points out, for instance, that casual use has reduced the term fascism in effect to something I dislike. Or, what in the world does tow the line mean? Not much unless you’re a water skier, and the reference would have little content even then. Orwell counsels writers to put original thought into their choice of words and phrases, adding precision while helping put the English language to rights. Doing so is a matter of cultural upkeep for him.

We start the winter term this week in Newport, and the influx of new students always puts the Naval Diplomat in an Orwellian frame of mind. That’s because we professorial types spend a lot of time during this opening week ruminating with students about how to write cogently and stylishly. We expend breath and brain cells reviewing how to write convincing essays because that’s a big part of how senior military officers and federal civilians — our graduates, in other words — communicate ideas to the even more senior commanders, diplomats and elected officials they advise. I got an excellent refresher on writing when I was a student in this department 22 or 23 years ago. It’s good to pay that forward.

Back to Asia. Spreading the theater, it seems, is an analogy to the spread offense that’s all the rage in football, at the college and high-school levels in particular. To oversimplify, spreading the field means lining up with the quarterback in the “shotgun,” well behind the offensive line in prime position to pass, while assigning large numbers of wide receivers along the flanks to run downfield. Such a formation compels the defenders to spread out as well.

It also imposes a dilemma on them. Should they allocate scarce manpower to cover the receivers closely and prevent a big play, or should more of them stick close to the line to guard against a running play or blitz the quarterback? Spreading the field thus means thinning out — and weakening — the defense. Executed well, the spread offense opens up passing lanes, weakens the defense against the run, and forces the other team to gamble — betting that a certain defensive scheme will match up with the play the offense runs next.

Now apply the sports metaphor to maritime Asia. The keywords in this phrase are spreading and theater. Take the second keyword first. Is the Indo-Pacific a unified theater? The idea that oceans and seas are one indivisible body of water — well, with the exception of landlocked expanses such as the Caspian Sea, anyway — dates at least back to Mahan’s writings. This question is worth debating, though. It makes sense for Admiral Locklear, whose area of responsibility spans the Pacific Ocean and much of the Indian Ocean, to think in such expansive terms. Others may not.

For instance, because of their geographic position — at the seam between the Indian Oceans, but along the southern periphery of Asia — Australians tend to embrace the idea of a single theater. But at the same time, with their modest diplomatic and military footprint, they often narrow their view of that theater to, say, the Bay of Bengal, the South China Sea, and the South Pacific. It’s rather as though each team member in our spread offense entertains a unique view of how to design and execute plays, and on what part of the field to execute them. And it’s as though there’s no quarterback to call plays — i.e., issue binding orders — and no coach to make the players run wind sprints until they drop if they disobey. If allies are the team players in Locklear’s spreading-the-theater strategy, it’s worth asking whether a common view of regional challenges and solutions prevails among the team.

Now take the spreading concept. It takes superior personnel to run the spread offense, not just coaching wizardry. A team with a quarterback who can’t throw straight, or receivers who can’t shake off pursuers or catch the ball, needn’t bother running such a scheme. The defense will simply concentrate all its strength at the line of scrimmage to stop the run, and the offense will stall. Similarly, if the United States, its allies, and its partners spread the field against, ahem, a certain large Asian country, they’re betting that they can mount multiple challenges along “exterior lines” to confound this defender, who operates on “interior lines.”

An interior power in effect operates along the radii of a circle, shifting assets around across short distances, while the exterior power has to operate around the circle’s circumference. The exterior position demands superior forces and coordination to succeed. To return to the football analogy, it’s rather as though the gridiron is triangular instead of rectangular, with the defense guarding a vertex. As the offense marches down the field, the field becomes narrower and narrower. With less and less turf to protect, the defenders can concentrate effort and power, and they can shift around rapidly to plug passing or running lanes opened by the spread formation. The offense has to be really strong, fast and smart to reach the end zone in the face of such built-in disadvantages.

So by all means let’s spread the theater. But let’s ask ourselves whether our players are good enough — and unified enough — to overcome the other team’s intrinsic advantages. If not, it’s time to draw up new plays, rethink our lineup, or have a heart-to-heart talk with our offensive coordinator.

Fun with metaphors.