Diplomatic relations between Jakarta and Canberra have slumped to lows not witnessed in more than a decade, with Australia’s refusal to provide a sufficient explanation for the bugging of Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s phone threatening the future of productive relations. While an apology may take the heat out of terse relations, it is clear that all is not well between the two nations.

The tipping point for an standoff came last week, when documents provided to The Guardian Australia and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation by Edward Snowden detailed the Australian Defence Signals Directorate’s extensive surveillance activities in Jakarta and the interception of Yudhoyono’s phone calls in August 2009. These revelations followed reports in Fairfax newspapers in late October, which detailed how Australia’s embassy in Jakarta serves as a signal base for espionage acts across the archipelago.

Paul Barratt, former Secretary to the Department of Defence, told The Diplomat that the ongoing fallout is one of the most challenging diplomatic issues for Australian-Indonesian relations since the East Timor intervention in 1999. “Relations are very testing because of the disrespect shown to Indonesia in the Australian public discourse,” said Mr. Barrett. “We need to start treating Indonesia like grownups and start behaving like grownups ourselves.”

His views are echoed by former Liberal Party leader John Hewson, who told The Diplomat that “there seems to be little doubt that monitoring the mobiles of the Indonesian President and his wife was a step too far.” He added that “the Indonesian-Australian relationship is very important, and is very important to both sides. In this sense, the issue can only be pushed so far.”

But unlike the phone-bugging revelations that rocked relations between German Chancellor Angela Merkel and U.S. President Barack Obama, which were largely dissolved with an apology and a promise to cease such acts in future, the refusal of Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott to apologize – with attrition equaling an admission of guilt – has provoked a wave of diplomatic and public retaliations in Indonesia.

After Abbott addressed the Parliament on Thursday afternoon, Yudhoyono took to Twitter to express his frustration to his 4 million-plus followers. “Today I instructed Minister Marty Natalegawa to recall Indonesia’s Ambassador to Australia. This is a firm diplomatic response. (…) I also regret the statement of Australian Prime Minister that belittled this tapping matter on Indonesia, without any remorse.”

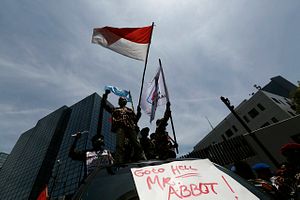

But it didn’t stop there. The Indonesian president temporarily suspended the intelligence and military cooperation with Australia so vital to Abbott’s election promise to “stop the boats” that bring asylum seekers to Australia by water, and threatened to cease further cooperation unless Abbott provided a sufficient explanation. By Friday evening, the gates the Australian Embassy on Jalan Rasuna Said were stained with eggshells hurled by protestors from the Islamic Defender Front (FPI) and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI), who earlier burnt images of Abbott and the Australian flag.

Indonesia is certainly not immune from criticism of foreign espionage. According to Dr. Hewson, espionage is always the elephant in the diplomatic room. “Everybody does it to some degree, and nobody wants to talk about it, especially if it becomes a matter of public allegations and discussion,” he said. “However, Indonesia doesn’t come to this issue with clean hands either, having admitted previously to having “spied” on Australia during the East Timor crisis.”

In 2004, Indonesia’s retiring Intelligence Chief Abdullah Mahmud Hendropriyono admitted on Australian television that Jakarta had bugged the Australian embassy in Jakarta and tapped the phones of Australian politicians. Since last week’s revelations, Yudhoyono has also moved to create the Central Intelligence Committee, to be administered by the State Intelligence Agency, which will open new branch offices and make foreign spies a priority target.

But it would be remiss to blame deteriorating relations exclusively on the espionage allegations, media commentary, or public protest. This fallout is instead the culmination of a year of diplomatic frustrations between Canberra and Jakarta, with both nations posturing for respective national elections and politicians often defaulting to megaphone diplomacy rather than nuanced discussion.

Mr. Barrett told The Diplomat that the rhetoric of the Australian Federal election in September this year was particularly problematic. “The then Opposition leader and now prime minister conducted a very aggressive campaign directed entirely to an Australian audience that basically said ‘it doesn’t matter what Indonesia thinks, we’re going to turn back the boats’. Unsurprisingly, people in Jakarta do think it matters what Indonesia thinks.”

With Indonesia set to vote for a new president in mid-July 2014, nationalism has returned to Indonesian politics. Professor Tim Lindsey, an Indonesian expert at The University of Melbourne Law School, believes that such domestic pressures contributed to Yudhoyono’s swift reprisal. He told The Diplomat that “the president is under fire in Indonesia as being something of a lame duck coming to the end of his term.” Already, Yudhoyono’s ailing Democratic Party is reported to have benefited in the polls from his strong stance against Australia.

Restoring a closer and more cooperative relationship with Jakarta is essential for Australia’s economic and geo-strategic interests in coming decades. The archipelago is the world’s third largest democracy, the most populous Islamic nation on earth, and straddles key shipping lanes in Southeast Asia. As Professor Lindsey put it: “Australian cannot do with Indonesia, while Indonesia could do without Australia.”

As a modern democracy on Australia’s doorstop, Indonesia’s influence in Southeast Asia is vital to Australia’s involvement in the region. David Hill, a Professor of Southeast Asian Studies and Chair of the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University, told The Diplomat that “Indonesia is rapidly assuming the status of a substantial player in the region and a substantial economic and political influence. Having Indonesia as a friend at the diplomatic table is greatly beneficial for Australia,”

But while a productive relationship may be vital for Australia’s strategic interests, the Australian public remains unfamiliar with its northern neighbor and prone to negative stereotypes. Research commissioned by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade revealed that only 47 percent of Australians believed Indonesia was a democracy, and 30 percent failed to recognize that Bali – a popular tourist destination for Australians – was part of Indonesia. While some 15,000 Indonesian students study in Australia, the number of Australians studying in Indonesia is in the dozens.

Indonesia’s economy may have slowed in recent months, with second quarter GDP growth falling to 5.81 percent, down from 6.03 percent in the first quarter, but the nation of 246 million people remains an important export market for Australia’s agriculture and mineral industries. The Gillard government’s suspension of live cattle exports to Indonesia in 2011 may have strained relations with Australia’s tenth largest export market, but demand for Australian cattle and beef remains relatively strong.

The immediate future of diplomatic relations between the two nations will be determined by both the contents of a letter sent by Abbott to Indonesia explaining the espionage revelations, and more significantly by the reaction of the Indonesian government. Yudhoyono has not yet made the diplomatic letter public and may not choose to do so.

For now, as Professor Hill notes, “It is not in the interests of either community to have a prolonged rift between governments spill over into much broader people-to-people relations. One would imagine that is in the minds of all leaders concerned.”

Henry Belot is a freelance journalist who has worked in both Jakarta and Melbourne.