Abdul Aminzai came all the way from Kandahar to participate in the ongoing India International Trade Fair in New Delhi, but his mind is on the debates taking place in the consultative Loya Jirga, an assembly of tribal elders, in Kabul. The assembly was convened to discuss the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) between Afghanistan and the United States. The carpet seller appeared baffled on Sunday evening when he discovered that President Karzai decided to delay the signing of the BSA — something he referred to as an “important agreement” and “crucial to peace and security” in Afghanistan.

“The security agreement with the United States is important for peace and security in Afghanistan after 2014. Without the presence of international troops, it will be difficult to stabilize the country. The Afghan army is still not strong enough to take on the Taliban, which has the backing of our neighboring country [Pakistan],” says 34-year-old Aminzai, who is looking forward to expanding his business in India. He fears that “any kind of uncertainty in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of NATO troops would ruin whatever business gains [he has] made in the last ten years.”

Ahmad Zia, a dry fruit seller from Kabul also expresses similar sentiments.

“I don’t understand why Karzai is not willing to listen to the overwhelming sentiment of the Loya Jirga for an immediate signing of the security agreement. If the President is keen for peace then he should not play games,” opines the Kabul-based entrepreneur.

The grand council of more than 2500 Afghan elders gathered from across the country in Kabul, endorsed the BSA, and as various reports suggest, favored signing the deal immediately. The main purpose of convening the council, which has more than a hundred years of tradition of engaging with rulers on important national issues, discuss the security agreement in a democratic forum.

The BBC writes that if the deal becomes a reality it will allow the presence of at least 15000 foreign troops at nine bases across Afghanistan after 2014, even after the departure of other foreign combat troops. Besides engaging in counter-terror operations, these soldiers would be involved in training and mentoring the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF).

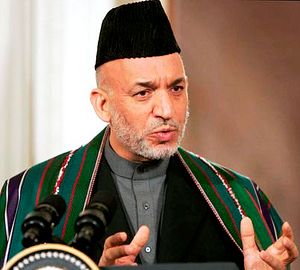

However, Karzai, despite recognizing and supporting the BSA, is not willing to ink the deal before the 2014 elections due in April next year thereby antagonizing the United States and contradicting the decision of the specially-convened Jirga.

Speaking to delegates in Kabul on the concluding day of the Grand Assembly, the president argued that “If [he signs] and there is no security, then who is going to be blamed for it? Afghanistan has always won the war but lost in politics.”

Deciphering Karzai’s contention, Kabul-based political analyst Habib Khan Totakhil told The Diplomat that “Karzai wants to ensure that the United States is doing enough to bring about peace and pressurize Pakistan to stop supporting the Taliban. Secondly, he wants to show people that he does not have any selfish interest in the BSA but that this is a national need. Thirdly, he is apprehensive that if he signs the pact and something goes wrong after the elections, he would be held responsible. However, the president also understands that he has to sign the agreement in the end otherwise he would put at risk all the progress that Afghanistan has made in the last one decade.”

Abdul Hakeem Mujahid, former Afghan Permanent Representative to the United Nations under the Taliban government and member of High Peace Council, in a conversation with The Diplomat says that “the BSA is a necessity for future peace in Afghanistan.” He, however, defends Karzai’s intransigence towards the deal.

“The President wants to make it very clear to the United States that the future presence of foreign troops will not mean house searches and fighting. They have to work basically for the facilitation of peace without indulging into any kind of anti-terror activities,” says the former Taliban leader.

But Obaid Ali of the Afghan Analysts Network (AAN), a Kabul-based think tank reads the situation differently. He points to the “contradiction between the Grand Assembly and Karzai.” He told The Diplomat that “there is a clear contradiction between the President and the elders. The 50 committees of the council endorse the deal and its immediate signing but Karzai delays it. Perhaps a sign of his waning influence among the council members. I don’t think this was a successful Loya Jirga.”

Kabul-based BBC journalist Bahar Joya says that “Karzai just wants to stick to power and does not want to lose his influence by signing the BSA at this stage. He wants to be seen as a man who is still in command. By signing the deal he fears losing his importance.”

What would be the consequences of Kabul failing to achieve an understanding with Washington on the deal before the end of 2013?

The Guardian writes that “without a deal, the US is unlikely to part with the $4bn (£2.50bn) a year needed to pay the Afghan army, or provide the helicopters and other equipment promised.”

The United States wants the deal to be signed sooner to properly plan a future course of action, including a final determination about troop counts post-2014. State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said: “We believe that signing sooner rather than later is essential to give Afghans certainty about their future before the upcoming elections, and enable the United States and other partners to plan for US presence after 2014. It is neither practical nor possible for us to further delay because of the uncertainty it would create.”

The uncertainty is already taking a toll on Afghanistan with many elites emigrating.

Tamana Ahmadi, a medicine student in Kabul Ueniversity, is planning to migrate to Canada with her family in a month’s time. She fears that after 2014 life would be difficult in her motherland.

“My family is apprehensive. My father does not want to see the uncertainty that he has witnessed after the withdrawal of the Soviet troops. The civil war after that forced him to take shelter in Pakistan. Again, during the Taliban regime, we became refugees in Pakistan. My family is anxious about what’s going to happen after 2014,” says the 21-year-old student.

Ahmadi told The Diplomat that her “father is taking the whole family to Canada to avoid the cycle of uncertainty that [they] have to face in Afghanistan.”

Meanwhile, Karzai’s stand on signing the BSA seems to have further strained the relationship between the United States and Afghanistan.

In a hard-hitting editorial, The New York Times writes that “managing a productive relationship with Afghanistan has always been difficult with Mr. Karzai, who is an unpredictable, even dangerous reed on which to build a cooperative future. And it is unclear if Afghanistan, driven by corruption, sectarian divisions and the Taliban insurgency can have any better governance when elections are held next April. Mr. Karzai’s long record of duplicitous behavior is just one of the many reasons it is tempting, after a decade of war and tremendous cost in lives and money, to argue that America should just wash its hands of Afghanistan. There is something unseemly about the United States having to cajole him into a military alliance that is intended to benefit his fragile country.”

In this political game of strategic maneuvering, it’s the ordinary citizens like Abdul Aminzai who suffer the most.

“I hope Afghanistan does not make the same mistakes it made after the departure of the Soviet troops in 1989. We don’t want the history to be repeated,” says a pensive Aminzai.