It is a challenge to write about a single year. Of course, that doesn’t keep people from trying around year’s end. Some will remember 2013 by a word or two (“twerk,” “selfie”), a person (Edward Snowden), or even just a political assessment (“Obama’s worst year”). But what does a year really mean in the context of history?

Historians find it easier to focus on years of transition: Rome’s rise and its fall in 476 A.D; the end of Columbus’s first voyage in 1492; the French revolution of 1789 and Napoleon’s defeat in 1815; the Great War of 1914 and the flawed peace of 1919. These dates stick out in the minds of many living in the West. But it is also important to remember that those in other parts of the globe may have their own historical turning points in mind.

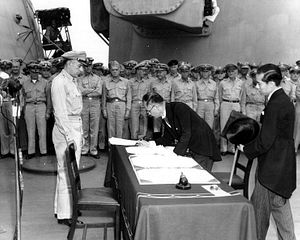

Ian Buruma’s Year Zero describes how the events of 1945 are different because of their global scope. Buruma himself is well suited to provide perspective. A Dutch expert on Japan and its culture, his father experienced the war as a forced laborer in Berlin. Buruma’s family history though is more the impetus to writing the book rather than the subject, which is the immediate aftermath of World War II in occupied Germany and Japan.

This was “Year Zero” in some ways, but not in others. Jubilation was short-lived as the occupiers began to understand the true scale of ruin in Europe and Asia. For some, this was an opportunity to build new institutions. Buruma makes clear, however, that most wanted to return to normalcy. Moderate conservative parties in Germany and Japan benefited from the desire for stability and a return to traditional values.

A new postwar order was imposed via the Potsdam Agreement and Declaration, leaving a divided Germany under the Allied powers and a pacifist Japan under the aegis of the United States. This helped ensconce Western Germany within the European project, but eventually left Japan to a “hopelessly polarized political dispute” over its dependence on the United States. The attempts to abolish “feudal” traditions in Japan or “denazify” and “reeducate” Germany, however, failed to bring about radical cultural change.

Moreover, the bitter memories of the past did not simply end under the new postwar order. It took decades for countries to reconcile in Europe and such a process was almost wholly absent from Asia. Buruma explains how Japan’s professed pacifism (now a “proactive pacifism” despite maintaining a capable military) and the lack of regional institutions akin to NATO or the European Union “poisoned Japan’s relations with the rest of Asia for decades.” In a recent opinion article, he expands on this theme by suggesting that the dangerous brinkmanship between China, Japan and the two Koreas is a symptom of their leaders’ family history. It is also unintentionally enabled by America’s continued military presence in the region.

If there is one deficiency in Buruma’s account of 1945, it is that he does not devote enough attention to this dilemma and make explicit how the lessons of the past can inform the present. But perhaps that is too large a task for a book about a single year. Nonetheless, the reader can still catch a glimpse of the seeds of discontent and recovery in 1945 that have shaped the world since in both Europe and Asia. This is particularly important for an American audience that has invested so heavily in both.

Parke Thomas Nicholson is the Senior Research Program Associate at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies in Washington, D.C.