During a high-profile rally in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) earlier this month Narendra Modi announced, “The time has come for at least a debate [on] Article 370.” Article 370 is a controversial constitutional provision that grants the state “special status” and by calling for a national conversation on it Modi – the prime ministerial candidate for India’s right-wing opposition party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – re-ignited an exhausted debate: what should be done about Kashmir?

The state – the birthplace of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister – is central to India’s nation-building vision of a secular, diverse and decentralized union, and J&K’s status vis-à-vis India remains an emotive issue. The BJP have long demanded Article 370 be scrapped and that Kashmir be fully integrated. The absence of any such absolutist demands in Modi’s speech triggered many excited murmurs that the BJP had shifted their position. But the party quickly dispelled any doubts, going into overdrive after the speech to reassure supporters that there had been “no deviation [from] or dilution [of]” the BJP’s commitment to integrating Jammu and Kashmir. Indeed M. Venkaiah Naidu, a party elder, pledged that the BJP would repeal Article 370 if they are elected into office in next year’s general election.

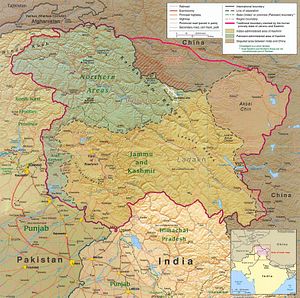

Scrapping the provision would be no easy feat, and many have asked if repealing the law is necessary, desirable or even possible. Article 370 grants Kashmir legislative autonomy and limits the power of the central Indian government to pass laws affecting the state. But since the provision came into force in 1954, successive Presidential Orders have stripped away the autonomy of J&K’s Constituent Assembly (governing body), extending New Delhi’s power over the state. Article 370 also plays a valuable accommodative role: as a majority Muslim state on the India-Pakistan border, J&K is afflicted by ethnic rivalries, terrorism and an ongoing territorial war. The resulting instability provides all the conditions required for a violent separatist revolt. India has historically granted political concessions to neuter such insurgencies and incorporate troubled regions, and Article 370 has achieved both of these ends in J&K. Finally as explained by Amitabh Matooh, a professor at the University of Melbourne, in The Hindu, J&K’s Constituent Assembly adopted Article 370 in 1956 giving it quasi-permanent force. Constitutionalists are unsure whether the sovereign federal parliament in Delhi can override the decision of a semi-autonomous state legislature. Any attempt to amend the Constitution would ultimately be subject to judicial review, leaving India’s Supreme Court with the final say on the matter.

The BJP are notorious for their “strategic oscillation” and having lost two general elections, Modi has been careful to avoid the party’s previous mistakes of appearing too hard-line. So far he has campaigned on the promise of economic development and he stuck to this script in Kashmir, when he insisted that integration with the Indian union would transform J&K from a “separate state” into a “super state.” As Rahul Srivasta reports, the Article 370 episode is notable because it is the first time Modi has strayed onto the party’s traditional territory and his deliberate effort to appear more moderate on this issue provides a rare insight into the shape a Modi-led BJP government might take.

But by forcing his party to reassert its unflinching commitment to Kashmiri integration, Modi’s “softened approach” backfired. This strategic own goal was made clearer by the many, inevitable, comparisons with Atal Bihari Vajpayee, India’s first and last BJP Prime Minister, who is credited with pioneering a pragmatic and progressive solution to the Kashmir question: integration through “insaniyat” (humanity).

Predictably, Modi’s attempt at triggering a national debate provoked anger from his many political opponents. Omar Abdullah, J&K’s Chief Minister, dismissed Modi’s remarks on rights and development in the state as “misleading” and “ignorant”; he was criticized for not once mentioning the problems of instability, terrorism and government oppression in the state during his 40-minute speech; and the promise of abrogating Article 370, popular among Indian nationalists but a proposal that risks alienating Kashmiris, lead Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, a former J&K Chief Minister, to accuse Modi of “trying to reap votes at the cost of the national interest.”

Even so, the most important question raised by the episode remains: what is India’s Kashmir policy? No alternative policy suggestions emerged from the political maelstrom, confirming widely held suspicions that the political pantry is now bare. Writing in The Indian Express Shekhar Gupta, a noted commentator, insisted the time is ripe for political creativity. Kashmir has enjoyed several years of relative peace and the state, he insists, is desperately in need of “a new set of peacetime political ideas.” For him Modi’s call for a “debate” presents an opportunity to question India’s military deployment in the state. India has stationed huge numbers of troops in J&K and they are accused of heinous abuses and rights violations. De-militarization, many insist, is a necessary first-step to rebuilding the trust deficits between Kashmir and New Delhi – a prerequisite to any long-term political solution to the Kashmir question.