During his fourth trip to Asia as Secretary of State this week, John Kerry is visiting Vietnam to “highlight the dramatic transformation in the bilateral relationship” between Washington and Hanoi. Indeed, in addition to security cooperation, bilateral trade has been thriving, up almost 60 percent in the past five years to $25 billion annually. Since the bilateral trade agreement of 2001, the United States has swiftly become Vietnam’s largest market for exports. Now, both countries are participating in negotiations on the massive Trans Pacific Partnership multilateral trade deal. Less promising, however, is the increasingly harsh reality of ongoing human rights abuses by the Vietnamese government.

Although the U.S. has repeatedly expressed intentions to address human rights concerns in its Vietnam relations, the situation has deteriorated in recent years, particularly its use of arbitrary detention to silence dissenters of all kinds. During her visit to the country last year, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton noted that moving the U.S.-Vietnam relationship forward would require that human rights issues in Vietnam be addressed. Unlike relations with China, the United States has real leverage with Vietnam, which relies heavily on a strong bilateral relationship. Now is the time to put human rights issues at the top of the agenda.

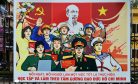

According to Freedom House, Vietnam, a country of some 90 million people, is “not free” and its government represses basic civil and political rights. The Communist Party of Vietnam remains the only legal political party. There is no free and independent media. Freedom of association and assembly are tightly restricted. The Vietnamese government has a long history of detaining individuals for exercising fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, association and religion, and in recent years these abuses have only intensified. Human Rights Watch has reported that in the first half of 2013, more than 50 people were convicted in political trials, already exceeding the total for all of 2012.

One prominent case is that of Catholic priest Father Thadeus Nguyen Van Ly, a leading dissident. For his role as a proponent of religious freedom and democracy in Vietnam, Father Ly has spent roughly 18 of the last 36 years in prison, and the government has continued to repeatedly re-arrest and detain him despite his deteriorating health. On two occasions this past decade, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found Father Ly’s detentions on propaganda charges to be arbitrary and called for his immediate release.

But Father Ly’s case is far from unique. Especially in the last three years, arbitrary detentions have grown rapidly. This increase is not only in the number of detentions, but also in the different kinds of individuals detained. Detainees are no longer limited just to dissidents. The trend has now expanded to musicians, bloggers, lawyers and union organizers. In February 2010, for instance, independent labor activists Doan Huy Chuong, Do Thi Minh Hanh, and Nguyen Doan Quoc Hung were sentenced to seven to nine years in prison for organizing workers at a shoe factory and distributing leaflets with their demands. Their closed-door trials violated many fair trial standards, as the accused were denied lawyers and prevented from speaking in their own defense during the proceedings. Last year, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found their arrest and detention to be arbitrary and in violation of international law regarding freedom of association and expression. Worse yet, throughout their detention, the government has subjected them to prolonged solitary confinement, poor food and sleeping conditions, forced labor and repeated beatings. This has resulted in severe health problems.

While in Hanoi, Kerry should deliver three key messages on human rights. First, the United States will not advance trade relations with Vietnam unless it sees substantial improvement in its human-rights record, including the release of its roughly 120 prisoners of conscience in Vietnam. Second, the United States will not expand military relations unless human rights improves. And finally, Kerry should inform Vietnam that the State Department plans to designate it as a country of particular concern under the International Religious Freedom Act, as has been recommended by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, thereby subjecting it to potential sanctions.

The United States has done much more than reach out its hand to Vietnam in recent years. It is time that there be consequences for Vietnam’s failure to unclench its fist.

Jared Genser is a lawyer and founder of Freedom Now, an organization that seeks to secure the release of prisoners of conscience, including those mentioned in this article. Greg McGillivary is a pro bono lawyer and partner at Woodley & McGillivary assisting Freedom Now on its Vietnam labor-rights cases.