In The Act of Killing, you encapsulate the Indonesian genocide and anti-communist purge of 1965-1966 where a million alleged communists, ethnic Chinese, and intellectuals were brutally oppressed and killed under the rule of General Suharto. How did the subject of your film come about and why did you decide to re-enact these slaughters?

I began making The Act of Killing in collaboration with a community of survivors of the 1965-1966 genocide. This was before I really knew about the genocide. I went in 2001-2002 to make a film on the Belgian-owned oil palm plantation facilitating the workers to document and dramatize their struggle to organize a union in the immediate aftermath of the Suharto dictatorship. The women workers desperately needed a union. This Belgian multinational spray of herbicide was dissolving their livers and killing them in their 40s, but they were afraid to organize a union that they so desperately needed because their parents and grandparents had been in a strong plantation workers union and had been killed for it, so they were accused of being communist sympathizers.

After we made that film they said come back right away (this was my first encounter with both Indonesia and the genocide) and make a film about why we are afraid. That is to say, not a film about what had happened in 1965. I think The Act of Killing is not really a film about what happened in 1965; it is a film about today. Similarly, they said come back and make a film as quickly as you can about still being afraid and what its like for us to live today with the perpetrators in positions of power all around us. We came back immediately and started filming but word quickly got out that we were now interested in what happened in 1965, and the army would no longer allow the survivors to participate in the film. The survivors with whom we were living said, “Before you give up, why don’t you try and approach some of the aging death squad leaders living in the village? They may speak and they may tell you what happened to our loved ones.” All they knew is that their relatives had been taken away and never came back but never really knew what had happened to them.

On the survivors’ request, we approached these perpetrators cautiously at first, unsure if it was safe to ask about the killings. But to our horror, every single one of the aging death squad leaders in the village would immediately tell boastful, detailed grizzly accounts of mass killings, often with smiles on their faces, often in front of their wives, their children, and even their grandchildren. There was this contact between survivors who were forced into silence and perpetrators who were boastfully recounting things that were far more incriminating than the survivors could ever possibly have told.

I felt as though I had wandered into Germany 40 years after the holocaust, only to find the Nazis still in power and I knew I would spend as long as it took to make a film addressing this condition of grotesque impunity. When I showed this early footage of the perpetrators back to those survivors who wanted to see it and then to the broader Indonesian human rights community, everybody who saw it said Joshua, you’re on to something terribly important, because with this material, when Indonesians see this boasting, when they see the way the perpetrators are talking, the way they’re almost performing rather than testifying, you will able to expose this whole regime. Any Indonesian who sees this will be forced to acknowledge the rotten heart of this regime, so feeling entrusted by the survivors and the human rights community I spent two years filming every perpetrator in North Sumatra that I could find.

At the end of the two-year process, I met Anwar Congo. He was the 41st perpetrator I had filmed and the scene at the beginning of the act of killing on the rooftop where he first showed me how he killed was the very first day I met him, and the final scene in the film where he finally returns to that rooftop was the very last day I filmed him five years later. The film’s method was a response to the boastful volunteering of demonstration and reenactment by the perpetrators themselves. It was not a trick to get them to open up; it was a response to their openness.

I said you participated in one of the biggest killings in human history and you want to show me what you’d done. I want to know what it means to you, how you want to be seen above all by the rest of your society by the rest of the world and how you see yourself, so show me what you’ve done, in whatever way you wish, I will help you make any reenactments you want to make, I will also film you and what your fellow death squad veterans want to show, what you don’t want to show, and why and thereby create a new form of documentary that answers this fundamental question of what this means to you, to your society, how you want to be seen, and how you see yourself. That’s how this project came about.

The Indonesian death squad members still serve and enjoy the protection of the state. Details of the purge are omitted from Indonesian schoolbooks. How is this film being received by native Indonesians?

The official history talks about the extermination of the Communist Party. That’s the term that’s used as a glorious and heroic victory without going into what that entails, mainly the imprisonment and tortured killings of hundreds of thousands or perhaps several million people. When you approach the actual executioners, whether they’re notorious, whether they’re famous, whether they’re powerful, or whether they’re living with relatives in anonymity, these are men who are haunted by the horror of specific, unimaginably awful memories of killing. In order to live with what they’ve done, they sugarcoat these awful rotten memories with this sparkling, beautiful but ultimately false patriotic rhetoric, and I think that actually comes out to be the origin of boasting.

Ranking perpetrators or people who were involved with actually killing people, they describe the most unspeakable and unimaginable things in this boastful patriotic rhetoric seeking to glorify it, seeking ultimately to justify it to themselves, and what that does is it gives the lie to the whole official history. The façade that genocide could be patriotic and heroic comes crumbling down. And that’s how the film has been perceived in Indonesia.

There’s a telling theme in The Act of Killing, where Adi (one of the killers) is watching one of the reenactments. He interrupts and says:

“Look, if we succeed in making this film it will turn the entire official history on its head and everybody will recognize we were the bad ones , and they will all recognize what we suspected to be the case is true, mainly that all the propaganda is a lie and that we’ve been lied to and that the killings were wrong.”

And that’s what the film has done, it’s what the survivors anticipated the film would do when they said keep filming the perpetrators. They are incriminating themselves and they are impugning the entire lie that this regime is based on; they’re undermining the entire lie that this regime is based on. The best part of releasing this film has been the reaction in Indonesia. The film has been screened thousands of times in hundreds of cities, but above all it led the media to finally break decades of silence on the genocide, and to discuss the genocide as a genocide. The perpetrators in Indonesia no longer boast.

Relatively mainstream publications have published long investigative reports on the genocide. Temple magazine for example came out with a special double edition on October 1, 2012 inspired by The Act of Killing. After the publisher of Temple saw the film, he called me and said, “Josh, there was a time before The Act of Killing, now there’s going to be a time after The Act of Killing. I’ve been censoring the genocide since I first arrived in this job. I’m not going to do it anymore because your film showed me above all that I do not want to grow old as a perpetrator. We are going to break our silence on the genocide in a way that supports your film by showing that The Act of Killing is a repeatable experiment. It could have been made anywhere; there are perhaps 10,000 Anwar Congos in this country, the problems of fear, corruption, and thuggery are systemic.” And they sent 60 journalists around the country to look for men like Anwar who would boast. In two weeks, they gathered nearly 1000 pages of boasting replicating what I did with the first 40 perpetrators I filmed in the two years before I met Anwar. They published 75 pages of this stuff plus 25 pages about the film.

This magazine is the biggest magazine in Indonesia. It sold out at once, they reprinted it, it sold out again they reprinted it, and it sold out again. Now its come out as a book because Indonesians were astonished that this holocaust that underpins the whole system, that the mainstream media never really discusses except in the most vague heroic terms, finally in gory detail was being described and addressed in the most important news publication in the country. The rest of the media inevitably followed suit and published their own reports. And so now as a result, there’s no stuffing the genie back in the bottle. It is indeed like the child in the emperor’s new clothes.

The film on its own can’t change the whole political system, it can’t end the use of gangsters in politics. It can’t outstrip the perpetrators of their power. But what it can do is open a space where ordinary Indonesians are finally able to address their most painful, intractable problems for the first time without fear. And from there, activism can follow. Grassroots movements against corruption and against impunity can either be reenergized or built.

Although it’s not a focal point of your film, you do allude to the fact that Western governments aided the massacre that ensued. For our readers, could you elaborate on this forgotten story of Cold War history?

The details of what individual Western governments did are somewhat obscure, but for example the United States provided cash for the death squad and the army, weapons, radios so the army could coordinate the killing campaigns across the 17,000-island archipelago, and death lists. I interviewed two retired CIA agents and a retired state department official whose job was to compile lists generally of public figures known publically to the army, compiled lists of thousands of names of people the U.S. wanted killed, and hand these names over to the army and then check off which ones had been killed. They would get the list back with the names ticked off [designating] who had been captured and killed.

The U.S. also produced propaganda seeking to drive a wedge between the People’s Republic of China and the new Indonesian regime. They produced propaganda out of the CIA stations in Bangkok and Singapore, basically saying that the Chinese Indonesians (ethnic minorities who had been there for hundreds of years) were somehow the masterminds of Indonesian communism presumably because China was a communist country. This particular geopolitical priority of the United States led to the slaughter of 50,000 ethnic Chinese who really had nothing to do with the Indonesian left.

The film doesn’t go into this sordid history mainly because it was quite clear to me that I was tasked with making a film about the present. As I said earlier, I don’t think this is a film about what happened in Indonesia in 1965, this is a film about today. I recognize that to go into the details of Western involvement and then to make a case of that involvement would be to line up experts and historians and have them present the case for one side or the other of that argument and that would be to make a historical documentary, a film that seeks to craft a coherent narrative of what happened and why. Whereas the task of this film is to show what happens when killers win, and the effects of the victors’ history, that is to say the lies that perpetrators tell to justify their actions at the level of an entire society and the level of individuals. Those are two different tasks and I recognized I could not do both in the same film. I instead opted for what I thought was the more urgent task, which was to expose a regime of impunity and thereby intervene in intolerable condition that the survivors and human rights community had asked me to address. Nevertheless, I tried to visually haunt a film with the specter of consumer capitalism, globalization and American cinema as a way of gesturing to our complicity, implicating the viewer wherever the viewer may be in the events that are unfolding onscreen.

All countries mythologize their histories. Do you see any correlation between Indonesia’s historical imagination and that of others? Don’t we all obscure the darkest moments of our pasts?

First of all, there’s a sort of absurd moment where Anwar says, “I’m trying to make a beautiful family film about mass-killing.” That absurd and grotesque project leads him to stage cowboy scenes about the killings. There’s a nod to the way Americans deal with their past. Anwar of course is choosing a genre whose fundamental purpose is to glorify the genocide of the Native Americans. We have a whole Hollywood genre here in the United States that exists to glorify genocide. It is the western and Anwar is using that to glorify his own local genocide, the genocide in which he participated. Building on that, it’s tempting to say the grotesque impunity we see in The Act of Killing is the exception to the rule. We’re used to hearing perpetrators in documentaries either deny what they’ve done or apologize for it and never to boast about it. I think normally documentarians approach perpetrators – it doesn’t happen very often – but when they do, the perpetrators have normally been forcefully removed from power. These men however have remained in power and have never been forced to admit what they’ve done was wrong. So they boast about what they’ve done. Not necessarily because they’re proud of it, but because they know what they’ve done is wrong and are desperately trying to convince themselves and force onto society the view that what they did was justified or heroic somehow.

I would say though that because normally when we hear perpetrators, they apologize or deny what they’ve done. Because of that we’re tempted to see this as the exception to the rule. I think it isn’t. The Nazis being removed from power, the Rwandan Hutu extremists being removed from power, that’s the exception to the rule. My guess is that perpetrators perpetrate violence. Mass political violence occurs in part because it’s effective for taking power and maintaining power. The impunity we see in The Act of Killing is the rule. Normally perpetrators win and once they win they write a victors history justifying what they’ve done, celebrating it as glorious and creating a narrative in which they are not perpetrators but heroes. The impunity is the rule and the boasting of the perpetrators in Indonesia is not a freakish exception to the rule. It is an allegory for that rule. Building yet again on this point that this not some freakish occurrence on the other side of the world, I would say look: Everything we buy, every article of clothing certainly touching my body at the moment, and even the telephone through which I’m speaking to you, all of it is produced in places like Indonesia, places across the global south where there’s been mass political violence where perpetrators have won, where in their victories they’ve built regimes of fear, where people who make everything we buy are too suppressed to effectively be able to get the human cost of what we buy, included in the price tag that we pay.

As I mentioned earlier, I began this journey with a community of palm oil plantation workers who are being killed to make a little bit of palm oil (which is in everything from skin cream and shampoo, to margarine and some food). In fact the real cost is incalculably high, and we only pay a tiny fraction of that cost because included in the price we pay for all these things is a small markup, a small premium, a small component of the price that goes to goons, and thugs and gangsters, like Anwar and his friends whose job is to keep the people who make everything we buy afraid, so that everything we buy remains cheap.

And in fact everybody who sees this film and who reads this interview already knows this. So that’s just to say this is not to see a distant reality on the other side of the world, it is the underbelly of our reality. The situation you see in The Act of Killing is the underbelly of our reality. If these men are monsters, which I think categorically they’re not, they’re human, but if one is tempted to say they’re monsters we must also concede that all of us depend on monsters like them for our everyday living, to feed ourselves, to clothe ourselves, to put petrol in our tanks and to live our lives. And what then does that say about us?

Parliamentary and presidential elections are set to take place this summer. Are you optimistic about Indonesia’s future social and political landscape?

I think we’re at a crossroads. The reaction of ordinary Indonesians to this film, the bravery and strategic intelligence in which they brought the film out in Indonesia has been heartening. On the other hand, there is a very real risk that Indonesia will backslide toward military dictatorship.

The leading contender in the presidential election is former Army General Prabowo Subianto, the son-in-law of Suharto, the dictator who created the genocide. He has the dubious distinction of being the very first person ever to be put on a blacklist for his role in masterminding mass murder and torture. That is to say, he’s not allowed in the United States. This is not to hold the U.S. up as some great judge of political moral conduct. Many of the atrocities that Prabowo is responsible for the U.S. supported tacitly or directly but I think that it’s very important for Indonesians to take impunity seriously. Every time The Act of Killing wins an award, every time it receives accolades, it puts the film back in the headlines in Indonesia and with it, the issues of impunity that it raises.

It’s a really important time for Indonesians to be talking about this film, and an important time for Indonesians to find the courage to confront their painful past, and the role of their present political leaders in masterminding that past and lying about it for decades.

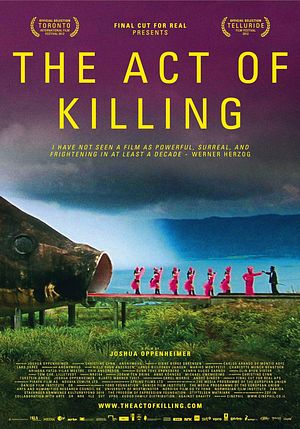

Official Trailer