Back in January, I had the pleasure of attending the Center for the National Interest’s annual conference, where one of the many distinguished speakers was Henry Kissinger, America’s most beloved realist. Early on in his remarks, Kissinger noted that the United States “is the only country in which being called a realist is a criticism.”

Indeed, while the American people are more sympathetic to realism than is often believed, there can be little doubt that realism is a dirty word among the political elites in the United States. This hostility derives largely from the belief that realism is morally nihilistic and cares little for things like democracy and freedom.

A perfect (if caricature) example of this viewpoint comes from James Kirchick, previously of RT fame and now a fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. On Monday, Kirchick published a piece in the Daily Beast that was appropriately titled “How the ‘Realists’ Misjudged Ukraine.” The piece argues that one similarity (of many apparently) between the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain and Russia’s recent invasion of Crimea is that both policies had apologists in the West. The Western apologists, according to Kirchick, are “these foreign policy ‘realists,’ identifiable by their abjuring a role for morality in American foreign policy and the necessity of US global leadership, [and] locate the real imperialists in Washington and Brussels, not Moscow.”

Kirchick declines to give an example of a realist individual from the Cold War era that fits this description. As far as contemporary ones go, he does briefly mention a tweet by Steven Walt, but focuses mainly on Stephen F. Cohen, a NYU and Princeton Professor who specializes in Russian history, and MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes. I’m not too familiar with either Cohen or Hayes’ work, though I had certainly heard of both of men before. From some research I can find nothing that suggest that Cohen is a realist, nor nothing that necessarily disqualifies him from being one.

It’s even harder to understand Kirchick’s reasoning with regards to Chris Hayes. As far as I can tell, Hayes has never demonstrated much of an interest at all in foreign policy issues. A look at the archive of his articles for The Nation, where he used to be an editor (Cohen’s married to the current editor), suggest most of his work has focused on U.S. domestic issues, where he usually takes the type of fairly far left leaning positions that one would expect from a primetime anchor at MSNBC. At times he has dabbled in foreign policy, and from what I can tell, usually takes positions on foreign policy that bear more resemblance to Noam Chomsky than Kenneth Waltz.

What’s clear from Kirchick’s use of Hayes and Cohen as examples of realists, instead of say Zbigniew Brezezinski, is that he defines realists solely in terms of the importance they place on democracy and values. Cohen was a realist because he provided a historically-informed narrative of Vladimir Putin and his recent actions in Ukraine (that I mostly disagreed with) that was much more favorable to the Russian leader than the dominant narrative in Western media. Hayes, on the other hand, is labeled a realist because he mocked John McCain’s tendency to see every international situation in black and white terms (For example, in Syria Assad and the Alawites are blood thirsty dictators in the mold of Stalin or Hitler, and the opposition is comprised solely of peace loving democrats.)

Whatever one thinks of Kirchick’s criticisms of Hayes and Cohen in general—I personally don’t disagree entirely with them—it’s unfortunate and somewhat ironic that realism is so often depicted in this way in the United States, given that American realists have done far more to spread democracy across the globe (starting at home) than their neoconservative and liberal internationalist counterparts.

Part of this is simply a reflection of the fact that American realists have been widely successful at spreading democracy, even if they didn’t subordinate every other goal to it. For example, it was realists that were in favor of the U.S. intervening in WWII to defeat Hitler and Imperial Japan and restore a balance of power in Europe and Asia.

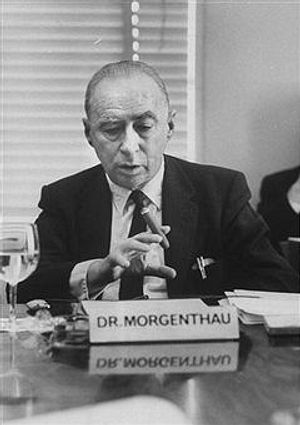

Similarly, it was realists like George Kennan and Hans Morgenthau that strongly advocated for the Marshall Plan and similar policies to shore up democracies in Europe and Japan after WWII. The same men also recognized that the Soviet Union contained “within it the seeds of its own decay,” and argued that preventing its expansion would ultimately cause it to implode. The wisdom of this policy was validated when the Iron Curtain fell (with the realist George H.W. Bush masterfully presiding over the collapse) without a major power war, and fledgling democracies began sprouting up across Eastern Europe.

It was also under largely realist Cold War administrations that Asian nations, which had little experience with democratic government, began embracing democracies in droves. Had these countries been pushed to become democratic in the 1950s, for instance, it’s hard to imagine them transitioning so successfully to democracies. Proof enough of this is that some of the least democratic parts of Asia—such as Vietnam and Cambodia—are countries where the U.S. went to war in the name of democracy despite the fierce opposition of realists like Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz.

This isn’t to say that realists have been perfect in their efforts to spread democracy; for instance, Nixon and Kissinger were the ones who went to China and to this day Beijing is a far cry from a liberal democracy. Even here, however, it is beyond dispute that the Chinese people enjoy much more freedom and prosperity than they did when Nixon arrived. While credit for this belongs overwhelming to the Chinese themselves, there’s no doubt that relations with the U.S. and its allies have helped Beijing recover from the disastrous Mao era.

American realists’ democracy promotion record looks particularly impressive when compared to neoconservatives and liberal internationalists, both of whom have proven to be utter failures in exporting democracy.

Of the two, liberal internationalists have had slightly more success. The Bill Clinton administration best embodied the liberal internationalist creed with its foreign policy of democracy enlargement. This policy was not without its successes—Clinton helped restore democracy in Haiti and intervened in the Western Balkans. Still, today Haiti is rated only “partly free” by Freedom House, and is wrecked with poverty. Many of the Western Balkan states have fared much better. Nonetheless, Freedom House recently assessed: “democracy is still far from being fully consolidated even in the best-performing states of the Western Balkans, namely Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia.”

More importantly, the crowning jewel of Clinton’s democracy engagement was supposed to be Russia. Yet, over the course of the Clinton administration a democratic Russia was plunged into chaos, which resulted in Vladimir Putin coming to power in the waning years of Clinton’s tenure in the White House. Similarly, in 2011 Barack Obama decided in favor of the liberal internationalists in his administration on the issue of Libya. And if Libya is no longer ruled by an autocratic government that is simply because it is no longer governed much at all.

Still, the liberal internationalists’ decidedly mixed record in spreading democracy can still be the envy of the Neoconservatives. No foreign policy faction in the United States has been so animated by the wisdom of democracy promotion, nor so convinced that the U.S. must play a primary role in this endeavor, as the Neoconservatives. Yet for all their good intentions, Neoconservatives have an atrocious record at promoting democracy abroad. The best that can be said of the Neocons’ policies is that they have resulted in many elections, albeit usually at the expense of much American blood and treasure. Nevertheless, the elections in places like Baghdad, Kabul and Gaza have produced no more democracy than those held in Putin’s Russia or Chavez’s Venezuela, and likely a lot less. Even the Neoconservatives’ prized case of Liberia seems to be falling apart.

The question therefore becomes how come the realists have been so successful at spreading democracy? Part of the reason is that, contrary to common perception, “Political Realism does not require, nor does it condone, indifference to political ideals and moral principles.” American realists, like most Americans, favor liberal democracies.

The larger reason for realists’ success in promoting democracy, however, is that they believe that “in order to improve society it is first necessary to understand the laws by which society lives,” and from this draw a “sharp distinction between the desirable and the possible-between what is desirable everywhere and at all times and what is possible under the concrete circumstances of time and place.” At the same time, realists fully appreciate that “we cannot conclude from the good intentions of a statesman that his foreign policies will be either morally praiseworthy or politically successful.”