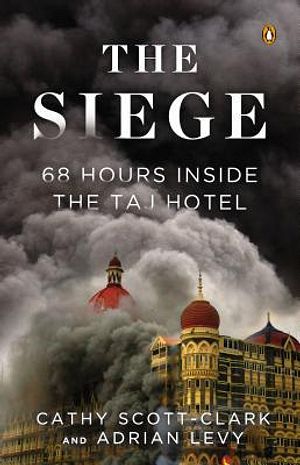

The Diplomat’s Gautham Ashok spoke recently with Adrian Levy, coauthor with Cathy Scott-Clark of The Siege: 68 Hours Inside the Taj Hotel, about the 2008 terrorist attacks on Mumbai and what lessons have been learned.

In the aftermath of the Mumbai attacks on 26/11, a lot of people especially in government circles said that such an attack could have occurred in any city, in any part of the world. Your book seems to indicate that something like this could have been prevented had certain measures been taken. Could you walk us through a few of the said measures?

First of all those two things are not mutually exclusive, it is possible for an attack of this kind to happen in any city of the world, and it’s possible that it could have been prevented. The question here is, how could have this attack been prevented?

It’s difficult to say really, you will remember that there was a huge amount of intelligence before the London bombings of 7/7, there was significant intelligence before 9/11 and yet those attacks were carried out. The reason being, government and intelligence agencies are not omnipresent. Having intelligence is not the same as catching the thieves. Having said that, what is clear with 26/11 is that a huge amount of intelligence was accrued. Much more than has ever been admitted, and that intelligence was either disregarded or in fact lay dormant until June 2008. Which means that there was two and half years’ worth of intelligence that was stockpiled somewhere and wasn’t acted upon.

Why did that happen? I suppose that question should be leveled at the new government that comes in next, because the current government has obviously refused to answer that question. One could hazard some guesses as to why this happened, educated guesses would point to competition between intelligence agencies, external and internal, a lack of honesty and forthrightness by the American intelligence community in dealing with India, their failure to communicate for narrow reasons of self-interest.

This leads to questions as to who was at the heart of American intelligence gathering, and what this meant. The fact that they had David Coleman Headly working for them was hidden and so on and so forth. There was also a culture that developed within intelligence circles, within the subcontinent in particular, where entrepreneurial spirit is not rewarded. The culture that has now developed within the Intelligence Bureau (IB) is one of paranoid back watching and extreme politicization. Free thinking is not encouraged or allowed.

After 9/11 and 7/7, extensive inquiries into intelligence failures were undertaken by governments in America and Britain. In India no such measure was undertaken. Do you think that the extreme secrecy that goes into the Research and Analysis Wing and the Intelligence Bureau makes them complacent in a way?

It makes them no better, evolution comes through lessons learnt and organizations that are inherently secretive cannot be trusted to do that on their own. That’s where oversight comes in, the golden rule of intelligence within a democracy is that you do not manufacture the product and act on the product yourself. That turns into a self-fulfilling wish cycle. What you do is you manufacture a product and everyone else debates it: Is it true? Is it rigorous? The reason the invasion of Iraq came about was that the product was invented and acted upon by the same group of people in America, and the reason why Kashmir has seen such bloodshed is because the product has been developed and acted upon by the IB.

I’d particularly point to the evolution in 1995 of the Ikhwan project in Kashmir. This is an exact example of an El Salvadorian death squad that has been created by the state, whereby the mass surrender of one form of insurgent was then used against others. The IB developed the product, they used the product themselves and now look what’s happened to Ikhwan in Kashmir and what it’s done.

The narrative structure of your book weaves together many perspectives, readers are given almost point-of-view chapters from many of the actors involved. What persuaded you to tell the story in such a fashion?

Well, I think the reason was to reach the widest possible audience. When I wrote Deception with Cathy, we wrote a book that we wanted to be a benchmark in dealing with such contentious issues. We wanted out facts to be undeniable; the notes section was as long as the book. In fact we had to upload it separately onto a website. This book is slightly different. I wanted to reach a really wide readership around the world, rather than just on the subcontinent. I wanted to make a lesson out of Mumbai, and also as a tribute to the city. I believe there is no epitaph to what happened, and a lot of the people you speak to are lacking closure.

It is quite evident you did extensive interviews for the book, having said that, how did you manage to select the characters that you did eventually select for the book? And what were the stories that stood out to you during the writing process?

It was really difficult, you know before history becomes history, what it is, is an argument. What an author then has to do is to weave together as many different views as possible. So, you take one event and interview as many as you can, and from that drag out a consensus. You then match interviews against technical data, data that could be phone messages, text messages, emails, CCTV, phone masks and so on. Once this is done, you create a timeline and a chronology, and then what you’ve got to decide is, in an objective fashion, what drives these narratives. Its character, character drives the narrative. Finally you identify within all of that stories that are every man’s stories. Stories that exemplify real moments of personal and collective crisis, which is the art of writing.

All the stories detailed in the book are so intense, for example the girl who was stuck in the computer room, who had just joined. She had won her job through the diligence of her father Faustine who had worked at the Taj for 30 years or so. His happiest day was when his daughter took up her job as a computer operator, and then came the bizarre cruelty of fate. The daughter trapped in the computer room, called her father who was hiding in the cold meat storage in the basement, the chime of the telephone identified his position to the terrorists and he was killed. The great chef from Goa, who called his son as he bled to death on the kitchen floor, was an image that was hard to shake out of my mind. Ordinary people becoming extraordinary, that transformation was surreal. Every story was special to me in that sense.

The way 26/11 as an event was covered was a watershed for the Indian media, there was a lot of criticism of the media for their roles in giving away the positions of the security forces for instance. Do you think this could have been better handled by the authorities?

It’s the government’s fault. Recently, when the Westgate siege took place in Nairobi, the Kenyan government created an isolated zone. What that means is you immediately bring down within that area the mobile phone communication; you bring down the press communication. In Mumbai, the situation was ludicrous. It was absolutely astounding that the press was allowed to have that kind of freedom. They never isolated any of the sites, they tried to with Chabad house but that didn’t work out either. The siege of the Taj Hotel is a lesson on how not to run a rescue operation.

Five years have now passed since the attacks of 26/11. Do you think Mumbai as a city and India as a country has recovered from the tragedy, and are you of the opinion that India is better prepared now to deal with attacks of this nature in the future?

I don’t think Mumbai or India has recovered from the events of that fateful November in 2008, I also do not think India is any better prepared to handle incidents of that magnitude in the future. The sad part is that nothing has changed. The government is saying that it is better prepared, but I see no evidence of that. Evidence of that would come if there was a commission of enquiry into 26/11. A commission would have given us a better understanding of the shape and structure of the organizations.

Governments do not this because I believe they are afraid of the big security issues. There is now a greater insecurity; there is also a great lack of closure. People in Mumbai, the thousands of folk I’ve talked to since researching and writing the book feel that their treatment after the attack was almost as despicable as it was during the siege. People who came forward were dismissed. Civilians who witnessed the attack, at Victoria Terminus, at Chabad House, at Cama Hospital, in the huts and slums that surround Cama hospital, in the Taj, the Oberoi you name it – their treatment afterwards by the authorities was appalling. People constantly tell us how they couldn’t believe how they had been dismissed by the state and the center. This then turned into a tit for tat war between India and Pakistan which didn’t really focus on the main topics. It devolved into a political issue, which suited the politicians but didn’t necessarily improve the security situation in the country.

Your book focuses on two characters in particular, David Coleman Headly and Ajmal Kasab. Kasab is portrayed as a victim of circumstance, namely grinding poverty that leads him into terrorist camps, whereas Headly is better off financially but more difficult to fathom. How did the dynamics of these vastly different characters combine to bring about 26/11?

In Jihad, the foot soldiers of the holy war are neither religious nor political. They tend to be the manipulated agrarian working class, and those people are taken out of their impoverished surroundings and offered something better. If one looks at the recruitment cycle in an area like the Punjab in Pakistan, and we simply look at who the pop idols are in this region, you’d be surprised that the pop idols are not cricketers or movie stars but Jihadis. There is no one else. The absence of a stable government also hurts; one goes another one comes in. We have to understand that the leadership of the Jihad is politicized but the boys who actually carried out the attacks were not. Maybe one of them was, but the other nine were not.