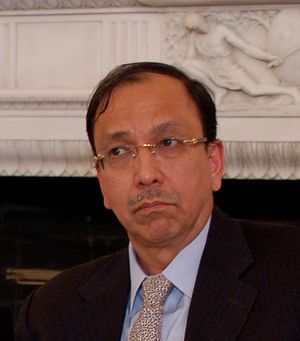

Professor Sugata Bose is a Harvard University historian, the author of His Majesty’s Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle against Empire (2011) and A Hundred Horizons: the Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire (2006), and a first-time politician. He is making a debut on a Trinamool Congress ticket from the eastern state of West Bengal in the ongoing general elections of India. The Diplomat speaks with him at his Kolkata residence about his books, his great-uncle Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s “mysterious” death, the communists, and the possibility of a third front in India.

As a historian, you’ve said that this is a critical moment in India’s history. You’ve also described the ongoing elections as historical elections. What makes you feel that?

(These elections are about) What kind of India are we going to have? On the one side, we have the politics of religious majoritarianism, combined with a politics of favoring the rich, the super rich in our country. And on the other side, the alternative we are trying to offer is that of federal unity, being respectful of the religious and linguistic diversity of this country and also fighting for the economic rights of a billion people and not just 70 billionaires whom we happen to posses in this country.

What’s your mood like now? Do you see a possibility of a third-front government?

There is one party that is trying to give the impression that the election is over even before the first vote is cast but it is absolutely clear to me that no party or alliance will come anywhere close to the majority and, therefore, I believe that the regional parties of the east and the south will do extremely well. We expect to win big from (West) Bengal and hope to have a say in the formation of the next government.

Will a third-front be a workable idea in India given that similar experiments earlier have proven disastrous?

I would distinguish the federal front that we have in mind from the third front of yesteryears. For one thing, the regional parties are much better entrenched in the various states of the east and the south than they were in the 1990s. What we still need to do is to have a cohesive government at the Centre and also formulate a coherent policy plank. I think it’s unfortunate that a federal front was not forged before the election, but I am sure that there will be a momentum towards the formation of such a front and also a renegotiation of our federal equation once the elections are over. Everybody is waiting to see which regional party will win how many seats.

Netaji Phirey aschhen (Netaji is coming back). Until not very long ago you could see wall graffiti somewhere or the other with these words. For a long time, a large number of people believed that India’s freedom fighter and your great-uncle Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose (1897-1945) is alive and would come back. There are several conspiracy theories surrounding his death. In His Majesty’s Opponent, you have given an account of Netaji’s untimely demise in a plane crash. But many still refuse to believe it. Netaji’s death remains as controversial as ever. What do you have to say, as a historian and a descendent?

I wrote my book as a historian and I wanted to focus on his life and work which I feel are far more important and relevant today than a fruitless controversy over his death. There was a mass psychological phenomenon in the immediate aftermath of the Indian independence and Partition. People wanted Netaji to be around and solve the country’s problems. I respect that sentiment. But sometimes there are utterly fantastic stories that are floated, which are not especially respectful towards the man who sacrificed his all for his country’s freedom. Even though I have dealt with the question of his mortal end in the last chapter of my book, I have I think been able to train the spotlight on his life and work. I have tried to show in that book that his life was actually more fascinating than the legend.

Netaji had joined forces with the Axis powers in the struggle for Indian independence from the British Empire. Some critics have said you have taken a simplistic view of his alliances with Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and imperialist Japan.

My book has been very positively reviewed across the world and, in fact, I think I have a very sophisticated interpretation of his decision to ally with the Axis Powers during the Second World War. He had been a participant in the Indian freedom struggle under Mahatma Gandhi for two decades from 1921. He had seen that the civilian masses in India had all joined the freedom struggle but the British had succeeded in keeping Indian soldiers who fought for the British Empire insulated from the swirling currents of civilian discontent in India and he felt that an international war crisis provided an opportunity for him to reach out to these soldiers and replace their loyalty to the King Emperor with a new loyalty to the cause of the Indian nation. In order to do that he had to go to countries where Indian prisoners of war were being held and that is why in the first instance, he went to Europe. He went via Moscow because the German-Soviet pact was still in force when he escaped, and to Italy. But then he saw that he had to move to Southeast Asia and in Southeast Asia he not only had a much larger contingent of Indian professional soldiers who came over to the side of Indian independence inspired by him, but he also had a much larger social base of support among Indian expatriates who lives in Southeast and East Asia at that time. So, my interpretation is, I think, on the mark as to why he chose to do what he did during the war time crisis.

Your party, the Trinamool Congress, was responsible for the complete rout of the communists in West Bengal after 34 years dominance in the 2011 Assembly elections. Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, the former chief minister of West Bengal, has been quoted in the media as saying that he hopes for a turnaround in the fortunes of his party, the Communisty Party of India (Marxists), in this elections. What’s your feeling?

I have great respect for genuine Leftists. In fact, I would be happy to describe myself as a Leftist in the sense that I believe that Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first Prime Minister) represented the Left tendency within the Indian National Congress before Independence. I would even say that there were idealistic communists whom I admired greatly, such as Benoy Choudhury who was the land reforms minister in West Bengal when the Left Front government was formed (1977). Unfortunately, the Left Front, especially the CPIM, has completely deviated from its ideas and ideology. It is bereft of any new ideas. It is practically leaderless, certainly in Bengal, but also at the all India level. So they are in a position of drift. I don’t see the Left recovering in Bengal in the foreseeable future. They do still have a certain vote bank which has been eroding fast. So, they will definitely be the second largest party in Bengal but I think they will be defeated by a wide margin this time. The only state where they are hanging on is Tripura. They are in a slightly better position in Kerala, but in Bengal they seem to be rudderless.

In A Hundred Horizons, you have written about the interconnectedness of nations on the rim of the Indian Ocean during the British Raj. In the present context, do you see a role for the Indian Ocean—the “wall of water”—fostering nationalist identities and goals, yet facilitating interaction among communities at the same time?

Historically, the Indian Ocean was an inter-regional arena bound together by very specialized flows of capital and labor, skills and services, ideas and culture. And I have written about that history and what I have shown is that these links were reordered but remained relevant in the period of the British imperial domination. In fact, you cannot offer an interpretation of the British Empire by simply concentrating on the territorial land mass of the sub-continent. You have to look at the larger Indian Ocean zone. Even when we were colonized, we had great thinkers and intellectuals who explored both the economic and the cultural ties between India and the lands across the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. One good example is Rabindranath Tagore. Think of his fascinating journey to Southeast Asia by sea in 1927 and I think Indian foreign policymakers should learn something from that kind of voyage. There is a cliché that I quite don’t like about hard power and soft power, but if I use it just at the moment for the sake of simplicity, India can actually project its soft power across the Indian Ocean by drawing on some of the earlier history of this shared cultural space. Unfortunately, I find that both the parties which claim to be all-India national parties have issued manifestoes which are extremely weak on foreign policy and especially in addressing the role that India should play in the Indian Ocean inter-regional arena and I hope that if we have a chance to formulate a foreign policy, the Indian Ocean zone will actually acquire a much greater salience.

What should be India’s approach towards regional partners in South Asia?

Our approach to the immediate South Asian region should be imaginative and generous so far as all of the relatively small countries of South Asia are concerned. We ought to give them open access to our markets. Our ambition is to play a role on the global stage and so we cannot allow problems at the regional level to constantly hobble us, and we ought to address and not evade problems even when it comes to Pakistan. We have to negotiate. Now it is a very difficult country with which to hold meaningful talks because even though they now have a civilian government, the military institution is still dominant. So Pakistan presents some special challenges, but so far as all the other countries of South Asia are concerned we can afford to be extremely generous. Give them many kinds of economic opportunities both in terms of opening up our markets, but also giving them credits for building their own infrastructure and so forth. And in terms of Pakistan we should have a purposeful sort of dialogue on various issues because we also don’t want the India-Pakistan issue to constantly stand in the way of our wanting to play a global role.

Your leader Mamata Banerjee, the current chief minister of West Bengal, is not seen as someone particularly kind to Bangladesh following her opposition to the Teesta water-sharing agreement and the Land Boundary Agreement that seeks to exchange pockets of land to settle boundary issues.

I think that was entirely the fault of the Central government. The central government did not take the state government into confidence. I think Mamata Banerjee and the Trinamool Congress Party as a whole have nothing but friendly feelings towards the people of Bangladesh and we are prepared to come to an agreement all outstanding issues, but you cannot have the central government simply inform the state government after they have taken all the decisions. I think just as Punjab has to be taken on board in talks with Pakistan, Tamil Nadu has to be taken on board in talks with Sri Lanka, so also West Bengal must be taken into confidence in advance when negotiating with Bangladesh.

How do you negotiate between your politician and academic selves?

We have multiple identities. I think my primary identity is that of a scholar and historian. I am simply trying to make a contribution in the political arena at a very critical moment in Indian history.

So it’s Mission Dilli Chalo (Onwards to Delhi), the slogan coined and immortalized by Netaji, for you now as you look forward to forming the next government at the Centre.

This is a democratic struggle to try and reach Delhi. Netaji had said the roads to Delhi are many and Delhi remains our goal. This is a political struggle from the east to reach Delhi and to offer the country an alternative that is I think far better than the one that is on offer from that Western state (Gujarat, where Narendra Modi, the prime ministerial candidate for the Bharatiya Janata Party, hails from).

Anuradha Sharma is an independent journalist based in Kolkata. She tweets @NuraSharma