Editor’s Note: These are the prepared remarks of a speech The Naval Diplomat gave in Barrington, Rhode Island on Memorial Day 2014

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Pericles, the “first citizen” of Athens, stood before that Greek city-state’s democratic assembly to give history’s first recorded – and arguably most celebrated – Memorial Day speech. So moved was President Abraham Lincoln by Pericles’ Funeral Oration that in 1863, when he traveled to hallowed ground at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, he modeled his own timeless address on it.

The occasion for Pericles’ oration was the end of a year of bloody strife against the rival city-state of Sparta. As it turned out, this was the first of twenty-seven years of hard fighting.

Pericles starts off his oration in a curious way. He says he wishes to honor the dead. But at the same time, he claims it’s hard for those who hear stories of valor to accept that their fellow citizens – people like them – are capable of deathless feats of arms. We question whether we could do the same – living up to their lofty standard.

In a way, then, the deeds of the fallen stand as a reproach to the living. We’re a bit ashamed – just as Shakespeare has Henry V jeer at the Englishmen who lie safe at home in their beds while their countrymen step onto the battlefield at Agincourt to fight a far stronger French army.

And yet Pericles reassures the assembly. He suggests that ordinary people can meet the standard thus set. Indeed, he insists they do so. That’s the point of his Memorial Day speech.

He goes on to depict the fallen both as Everyman and as the best of Athenian society. This is an important connection to make. Seafaring societies like Athens, or America, tend to be free societies. Rather than conscript manpower, Athens relied on volunteers to man both the infantry and the Greek world’s finest navy. Citizens, not slaves, rowed merchant and naval ships across the waves. They did battle for survival, for the national interest, and for renown.

So when Athenian fighting men took the field, they did so as stakeholders in a common enterprise – not because they were driven to it by the lash. They confronted danger of their own accord. That gives free societies an edge – so long as that spirit of voluntarism endures. We live and die by the willingness of the common man – of our brothers, and these days our sisters – to dare all, and perhaps to give all.

In short, the first citizen of Athens celebrated the heroics and self-sacrifice of Everyman. He reassured ordinary Athenians that such feats were not beyond them. And he challenged ordinary Athenians to live up to Everyman’s example – to make themselves worthy of the honored dead, and to carry their legacy forward. This was a matter of national well-being.

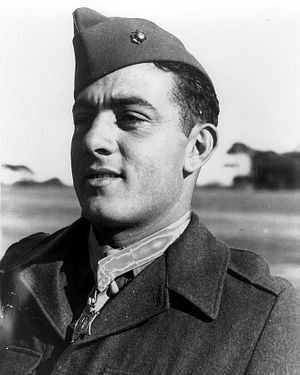

Now let me tell you a story about an American Everyman, a United States Marine by the name of John Basilone. A native of Buffalo, New York, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone was the sixth of ten children of Italian immigrants. He served in the Philippine Islands with the United States Army in the late 1930s before enlisting in the Marine Corps in 1940, on the eve of U.S. entry into World War II.

He was evidently quite the pugilist, winning boxing championships in the Philippines. Which would serve him well. In August 1942, Basilone landed in the initial wave at Guadalcanal, part of the Solomon Islands chain northeast of Australia and due east of New Guinea. The Imperial Japanese Army had been building an airfield on the island since May. Presumably the Japanese meant to station fighter aircraft there, cutting the shipping lanes connecting Australia with North America. Allied leaders agreed to contest the Japanese effort, in hopes of keeping the lifeline to Australia open.

Sergeant Basilone was a member of Company D, 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. Commanding his battalion was Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, a legendary figure in his own right. The key event for Basilone on Guadalcanal came in late October 1942, when his machine-gun detachment was assigned to a lightly defended sector of the defense perimeter around Henderson Field, which the Marines had successfully wrested from the Japanese.

And the Japanese Army wanted it back. As the fortunes of war had it, that weak spot was where the Japanese chose to make their major assault.

Let me give you some numbers to describe what came next.

72. That’s how many hours the battle raged, with no respite, in a narrow ravine.

3,000. That’s how many soldiers of the Japanese 2nd Division crashed into the Marine perimeter.

15. That’s how many Marines Basilone had to fight off the Japanese assault.

And 3. That’s how many of his Marines still stood at the end.

Three thousand to fifteen. Truly, that’s the stuff of legend. But don’t take it from me. Here’s what President Franklin Roosevelt had to say about Basilone’s actions in his Medal of Honor citation:

“For extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action against enemy Japanese forces, above and beyond the call of duty, while serving with the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division in the Lunga Area, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on 24 and 25 October 1942. While the enemy was hammering at the Marines’ defensive positions, Sgt. BASILONE, in charge of 2 sections of heavy machine guns, fought valiantly to check the savage and determined assault. In a fierce frontal attack with the Japanese blasting his guns with grenades and mortar fire, one of Sgt. BASILONE’S sections, with its gun crews, was put out of action, leaving only 2 men able to carry on. Moving an extra gun into position, he placed it in action, then, under continual fire, repaired another and personally manned it, gallantly holding his line until replacements arrived. A little later, with ammunition critically low and the supply lines cut off, Sgt. BASILONE, at great risk of his life and in the face of continued enemy attack, battled his way through hostile lines with urgently needed shells for his gunners, thereby contributing in large measure to the virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment. His great personal valor and courageous initiative were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. [Signed,] Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Nor does John Basilone’s story end there. After a tour back stateside selling war bonds, he insisted on returning to the Pacific. In February 1945 he took part in the landing on Iwo Jima, helping the Navy and Marines breach the Japanese Empire’s inner defense perimeter. His story did end there. While displaying the same raw courage that earned him the Medal of Honor, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone was killed by shrapnel on the first day of combat. The Marine Corps acknowledged his actions with the Navy Cross, the nation’s second-highest award for battlefield heroism. That made him the only United States Marine thus decorated during World War II.

Unbelievable, isn’t it? That is a lot to live up to. Now you see why Pericles worried he would dishearten his countrymen by recounting tales of martial gallantry. Can we live up to the standard set by John Basilone? I believe so. People of valor live today. Some of them wear military uniforms. I have the pleasure to work with them every day, in Newport and sometimes on foreign stations.

But valor is not exclusively a military thing. Just read the daily news. How often do we hear about Americans – regular people like us – running into burning buildings, or performing other feats demanding what looks like superhuman courage?

We need not look far away, or into the remote past, to find such examples. Just this past March a nine-alarm fire engulfed a four-story building on Beacon Street, in Boston’s Back Bay. Fire Lieutenant Edward J. Walsh Jr. and Firefighter Michael R. Kennedy ventured into danger – rescuing the people trapped in the building, before succumbing to flames, heat, and smoke.

They did their duty – and then some. Like John Basilone, Edward Walsh and Michael Kennedy gave the last full measure of devotion for the common good. I believe John would welcome them into a fellowship of honor, alongside military heroes of old.

Let me close by quoting an Army general and a contemporary of Gunnery Sergeant Basilone, George S. Patton. Shortly after World War II, at a gathering not unlike this one, Patton pronounced it “foolish and wrong to mourn the men who died. Rather we should thank God that such men lived.” Just so. I would only add that such people walk among us today – still.

Thank you.