How long will the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham’s (ISIS) bloody rampage in Iraq last? That is the question India’s financiers are asking as they brace themselves for the impact of the instability in Iraq on India’s economy.

India is a precariously energy insecure country: it is home to 17 percent of the world’s population but has a mere 0.03 percent of its oil reserves, 0.7 percent of its gas reserves and 7 percent of its coal. India’s enormous energy needs are met almost entirely by imports – it is the world’s fourth largest oil importer – a significant proportion of which come from the Middle East.

India imports 500,000 barrels of oil from Iraq every day. So great is India’s reliance on Iraq’s supply that the governor of India’s central bank, Raghuram Rajan, issued a statement on June 17 to make clear that he was closely monitoring the situation for any possible disruption.

The instability “will not result in a shortage of petroleum products,” says Amit Bandari, a researcher on energy and the environment at the Mumbai-based think tank Gateway House. “India’s oil exports are processed to produce fuels such as diesel and petrol – far in excess of what is consumed domestically.”

But oil is integral to India’s resource-intensive economy, with its price “running through” the transport and agriculture sectors. For ordinary consumers in India, therefore, the violence in Iraq will mean increases in the costs of traveling and produce.

In fiscal terms, the real impact lies with the cost of imports. At the beginning of June the cost of importing a barrel of Brent crude was $106.88, a figure that peaked and then fell slightly to $112 by June 17. India imports almost two million barrels of oil per day, so increased costs will further widen India’s already gaping balance-of-payments deficit.

As Bhaskar Chakraborty, a Mumbai-based energy analyst, told the Financial Times, “If crude goes up, India’s import bill goes up, so the cost of fuel and fertilizer subsidies go up, and the rupee comes under immediate pressure.” Indeed the rupee has been hit hard, slumping to 60.24 against the dollar on June 20, a low last plumbed in April.

In the face of this exchange-rate volatility, Raghuram Rajan was keen to reassure that India has slowly re-amassed its foreign currency reserves. As of June 13 its reserves totaled $313.536 billion, more than enough to see through the fluctuations in the rupee’s rate.

But these are a worrying cocktail of factors. This week Moody’s, the ratings agency, published a research report blaming budget deficits, high inflation levels and widening current-account deficits for the slowdown in India’s growth rates since 2011. These are all factors rearing their heads in the wake of the violence in Iraq, prompting stark conclusions about India’s growth outlook. Barclays, in a widely reported estimate, predicts that the price of oil could cut India’s annual growth rate by 0.5 percent.

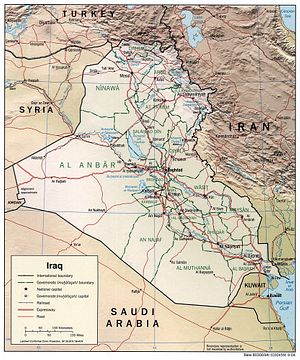

Of course, the security of Indian citizens in Iraq is no less important. As many as 18,000 Indian workers are employed in Iraq, the majority of which are manual laborers in the oil and construction industries. On Wednesday, fears about their safety were realized when India’s Ministry of External Affairs reported that 40 workers had been kidnapped from Mosul, the northern Iraqi city that ISIS violently seized on June 6. The workers were reportedly taken hostage whilst being evacuated, and both the identity of the abductors and the whereabouts of the captives remains unknown. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pledged to make every effort to ensure their safe return, and India responded quickly by dispatching its former ambassador to Iraq, Suresh Reddy, to Mosul. India’s national security advisor, Ajit Doval, is coordinating the rescue effort.