In the past year, the cauldron that is the greater Middle East has finally reached a boil after simmering for decades. Iraq is close to the edge of disintegration while Syria’s brutal civil war grinds on. Egypt has reverted to a de facto military state and Kurdish independence seems all the more likely.

What does this all mean? What will the region’s future be like? David Fromkin, the author of A Peace to End All Peace said in 2007 that “the Middle East has no future.” I happen to disagree. I believe that the future of the Middle East is truly beginning now because the old, convoluted Middle East that wasn’t working is finally in the process of irreversible collapse. Like an old phoenix that must burn to ashes before giving rise to a newer, more vibrant creature, the current convulsions around the Middle East will eventually give rise to a most stable political configuration. Of course there will be a period of instability before this occurs. But the Middle East as it currently stands is inherently unstable and trying to forestall instability is to merely prolong the lives of barely functional regimes and states. If a collapse is coming, it is better to get it over with sooner rather than later.

As I argued in a previous article, states often do not fit the realities on the ground created by groups. This is natural and should not necessarily be resisted. Jeffery Goldberg, writing in The Atlantic, concurs, arguing that “Westphalian obsessiveness — Iraq must stay together because it must stay together — just doesn’t seem wise.” Goldberg notes that “it is, of course, important to invest in plans that forestall the creation of permanent jihadist safe havens, and about this the U.S. should be vigilant, more vigilant than it has been,” but other than this obvious corollary, there is no point in Western intervention.

If there is one country to watch in order to understand the future of the region, it is Iran, the probable long term winner in the Middle East. Turkey is too remote, geographically and culturally, from the heart of the Middle East to ultimately reassert itself in the region and it does not have the extensive ground-level contacts that Iran has in many of the Arab states. Saudi Arabia is even less likely to be the region’s dominant power as it has a relatively low population, weak institutions, and is wholly dependent on oil. Iran’s likelihood of being the region’s main power should be fairly obvious from a study of history and geography, but there is a tendency in some circles in the United States to wish away these elements of geopolitics for idealism, a stance that has come back to haunt the world in the case of Iraq.

Iran is uniquely poised to help stabilize the region in whatever form it emerges after this period of readjustment and realignment. It can assist Afghanistan in countering Pakistan’s mischief and provide the necessary assistance Iraq and Syria need in order to keep them from being overrun by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS). It can provide security in the Persian Gulf and is a key player in Lebanon. This is not to deny that Iran has itself caused trouble by supporting groups such as Hezbollah, but Iran has a relatively tight leash on these groups. Moreover, these groups are more coherent in terms of organization and ideology than various radical Sunni militant outfits, many of which tend to be independent actors. All in all, militant groups aligned with Iran, whether Shia or not, tend to be more pragmatic and moderate in relation to Sunni militant groups.

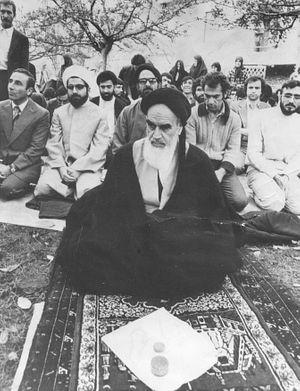

Many in the West and the United States in particular unfortunately have strong misconceptions about Iran and the nature of its regime. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 that placed power in clerical hands in Iran is not analogous to the attempted takeovers of some Sunni Muslim states by militant groups. While groups such as ISIS attempt to essentially destroy states and establish a new order, in Iran existing state institutions were merely Islamified by a highly sophisticated clergy which took over a well-developed, strong, and cultured state and mostly appropriated it for new ends. An appropriate analogy would be that of high ranking Catholic clergy taking over the institutions of say, Italy.

As journalist Robert Kaplan has often argued, Iran is essentially an oasis of stability in a desert of weak states because of its coherence and sense of naturalness. Yet by marginalizing Iran, the United States has prevented it from playing a constructive role in the region and strengthened the hand of its Sunni rivals, especially Saudi Arabia. Trying to shut a state as pivotal as Iran out of regional geopolitics is like attempting to have an East Asia strategy that ignores China. Ultimately, Saudi Arabia and its Sunni allies in the Gulf are a bigger threat to regional stability than Iran because they are weak, unstable states. More importantly, they fund and spread radical interpretations of Islam that spawn radical groups and destabilize countries from Pakistan to Iraq. Ultimately, both the U.S. and Iran are on the same page about facing this threat. Facts such as these mean that the nuclear issue will take a back seat for a long time to come.

That the relationship between Iran and the United States has been nonproductive is not only due to the United States. Iran has also made miscalculations that have required it to reassess its foreign policy periodically. After the Revolution, Iran sought to shift its narrative away from Persian nationalism to Pan-Islamic solidarity in an attempt to posit itself as the leader of the Islamic world. This necessarily required an antagonistic attitude towards the United States and Israel. This strategy, however, failed because pan-Islamic solidarity never held up against the Sunni-Shia rivalry, especially after the global proliferation of Sunni militant groups over the past decade and Saudi Arabia’s policies. Denunciations of Israel and America are now only useful domestically for some factions in Iran but in foreign policy terms increasingly serve little purpose. As Iran’s narrative increasingly shifts to Shia-solidarity and a possible revival of Persian nationalism, so too will its rhetoric and perception of which countries are its enemies.

In the new Middle East, Iran and the United States are not going to become allies. This is neither possible nor desirable for both countries. Nonetheless, as the current crisis in Iraq has demonstrated, Iran and the United States will begin to communicate more as their interests converge. In the course of the next few years, Iran and the U.S. will increasingly cooperate towards common goals with Iran playing a leading role in shaping the new Middle East, with much more American acquiescence than would have seemed possible merely a decade ago.