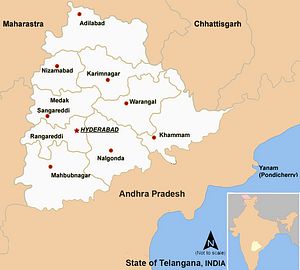

This Monday, India’s 29th and newest state, Telangana, officially came into being, having been split off from the state of Andhra Pradesh, the rump of which has retained that name. This is the culmination of one of India’s longest and most contentious domestic political movements, the agitation of several groups in Telangana for separation from Andhra Pradesh. These efforts finally came to fruition this political cycle, mainly because of the political calculations of the ruling Congress Party rather than any sympathy on the part of the central government for the cause of Telangana.

The creation of Telangana is especially notable because it is the first time an ethnolinguistic group — the Andhra or Telugu people — have been divided into multiple states outside of the vast Hindi speaking belt in northern India (Bengali speakers make up the majority in two states, West Bengal and Tripura but that is due more to recent demographic shifts in Tripura, which was not originally a Bengali majority region). This itself was seen as contentious as it sets a precedent for the reversal of the logic that has governed India’s states since the States Reorganization Act in 1956, which aimed to create one state per major language, with the exception of the vast Hindi belt. One of the many criticisms of the bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh came from Telugu nationalists who did not want their people to be divided into two states.

The genesis of Telangana lies in India’s complicated political history which has ensured that many ethnic groups have spent little time united under the same administrative unit. In the case of the Telugu people, the last time they were arguably united under a single administrative structure was during the Kakatiya Dynasty, which fell in the early 14th century to the Delhi Sultanate. Afterwards, most of today’s Telangana came under Muslim rule under the Bahmini and Golconda Sultanates before eventually coming under Mughal rule and its successor state, Hyderabad. Various sources have described the socioeconomic situation of Telangana during the past few centuries as exploitive and feudal, a situation culminating in a Communist-led peasant revolt before the Princely state’s annexation into independent India.

Meanwhile, today’s Andhra Pradesh developed independently of Telangana, becoming a part of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire and its successor principalities before being directly ruled by the British as part of their Madras Presidency. Unlike in Telangana, ruled by the Nizam of Hyderabad, the British collected revenue directly from peasants without the aid of feudal middlemen. This led to a more prosperous, developed region, mainly due to better administration, a fact reflected in today’s statistics. For example, Andhra Pradesh without Telangana has suddenly become one of India’s most literate states, with a literacy rate of 91.1 percent as opposed to Telangana’s 66.5 percent.

These sorts of disparities are at the heart of the Telangana movement’s argument for a separate state and give truth to the fact that one cannot simply wish away inherited historical differences. The argument is that a separate Telangana can focus solely on its own development and infrastructure while in the previously undivided Andhra Pradesh the region was neglected by the state government, dominated by politicians from the more prosperous coastal regions. Critics point out that on its own, Telangana is an arid, landlocked region that will be cut off from the greater revenue of Andhra Pradesh. Furthermore, creating a new state will require additional expenditure for a new government and bureaucracy, instead of that money being used on development.

Nonetheless, from a larger point of view, the separation of Andhra Pradesh into two states is demonstrative of positive trends. It signifies a change in focus among Indians from identity politics to developmental issues. It is not illogical for the same ethnic group to be spread out over many states because of the various developmental and geographical differences present in India. India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru was rightly suspicious of single language based states, worrying that those would fuel regional and possible separationist aspirations. He resisted the creation of such states as long as he could. This is not to argue that numerous language groups should be thrown into the same state as this would make administration and education difficult, but rather that ethnic groups should be distributed among various states, similar to the way that the same linguistic group in Switzerland is spread out over many cantons but with few multilingual cantons.

India badly needs some centralized, strong decision making at the federal level instead of the centrifugal regional forces that have paralyzed policymaking. These forces are especially strong in states such as Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Splitting up single ethnic group states dilutes regionalism and has the effect of preventing any one strong regional boss from dominating an entire region while not cooperating with the center. Thus breaking up provinces can paradoxically help centralization by preventing the concentration of power in large states despite the fact that it creates more units for the government to deal with.

Despite the increased administrative costs of setting up new governments, there is much to be said about improved governance for smaller states. Some Indian states such as Uttar Pradesh (population of around two hundred million) have as many people as countries such as Brazil and are quite unwieldy. Smaller states would be more responsible to individuals and more focused on a smaller, more specific region, helping development. Administration in the new, small states of Uttarakhand and Chhattisgarh has improved since their creation in 2000. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, there are numerous contentious issues yet to be resolved, such as the final status of the former state’s capital Hyderabad, which must be shared by both states for 10 years and the division of the former states’ revenues, properties, and employees. Nonetheless, the division of the state sets a welcome precedent for India and will hopefully improve governance in both the new states, though the manner in which it came about — for the electoral convenience of a single party — was of course, undesirable.

Akhilesh Pillalamarri is an Editorial Assistant at The Diplomat.