The U.S. and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) recently concluded the 6th Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED). Even before the meeting, there was skepticism that anything noteworthy would result. After all, the run-up to the meeting found American officials expressing discontent about China’s currency policies, industrial espionage, and concessions in ongoing Information Technology Agreement negotiations. For its part, Beijing voiced concerns about Washington’s plans to wind down quantitative easing, excessive use of anti-dumping and countervailing duties, and restrictions on Chinese companies pursuing opportunities in the U.S. On the political front, friction between the two countries has been growing. American elites deem China’s assertiveness in the East and South China Sea dangerous and fret China wants to push the U.S. out of the Asia-Pacific. Chinese elites charge the U.S. with containing China and adopting policies that encourage Japanese and Filipino aggressiveness.

S&ED economic tracks over the past four years have certainly produced many pledges. Unfortunately, many are repetitions of prior promises. For example, China has consistently committed to improve its enforcement of intellectual property rights, to further open its service sector to foreign involvement, to rebalance its economy, to reduce its dependence on exports, and to intervene less to support the renminbi. The S&ED strategic track has found Beijing and Washington repeatedly tackling the same security issues, such as Iran, as well as voicing support for increased military-to-military exchanges. Of note, in May 2011, both countries established the Strategic Security Dialogue (SSD) to enhance mutual trust, explore cooperation, and eliminate misperceptions.

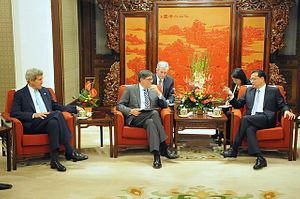

The most recent S&ED had three main features: perception management, pronouncements and promises. On perception management, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that confrontation was dangerous, that China needed a peaceful and stable environment “more than ever,” and that “the broad Pacific Ocean has ample to accommodate our great nations.” U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry pronounced that the U.S. was not containing China, that strategic rivalry was not preordained, and the U.S. “welcomed the emergence of a stable, peaceful, and prosperous China” that “contributes to the stability and development of the region, and chooses to play a responsible role in world affairs.”

As for pronouncements, the two sides staked out their positions on old issues like North Korea, “new” issues like cybersecurity, American alliances in the Asia-Pacific, the South China Sea maelstrom, and hotspots like Syria. Turning to promises, the U.S. and China agreed to boost military ties and counter-terrorism cooperation, though details were lacking. Economic outcomes were more noteworthy. China stated, for the first time in the S&ED joint document, that it would “reduce foreign exchange intervention as conditions permit and increase exchange rate flexibility.” It also committed to reach an agreement on core bilateral investment treaty issues and major articles by end of 2014 and initiate negotiation in early 2015 on the specifics of the associated “negative list.” Aside from this, China promised to let the market play a bigger role in determining energy prices and to remove restrictions on foreign investment in a slew of sectors. Washington agreed to ease the path for Chinese investments into the U.S. and ensure Chinese firms competed on a level playing field.

This is relatively unimpressive. Proponents of the S&ED, however, remain unconcerned. For them, any progress is valuable and, in any event, conversation is more important than the outcomes. Additionally, the S&ED enhances mutual understanding, facilitates closer relationships and habits of cooperation, and demonstrates the U.S. and China can work together. More concretely, the S&ED has spawned additional dialogues such as the SSD, created an opportunity for interaction among American and Chinese ministries that would not otherwise meet, and has improved coordination among Chinese ministries. It is not clear, however, that the S&ED format is accomplishing many of the aforementioned things. S&EDs do not involve dialogue, but pronouncements; do not build closer relationships; and have not eliminated misperceptions. Worse, perhaps, the S&ED seems to contribute little in the way of agreement on what the policy problems are.

The S&ED has manifold design flaws that limit what it can achieve. First, it involves too many people. Regardless of how many sub-dialogues and breakout sessions there are, several hundred participants do not allow for extensive and intensive interaction. Second, the right people need to be involved. For example, it is not enough to include the Chinese State Councilor for foreign affairs and Foreign Minister, given their non-authoritative roles in the construction of Chinese foreign policy. On the American side, members of Congress need to be included given their ability to hinder the fulfillment of U.S. government promises. Third, while the American preference for deliverables and getting down to business is not always the ideal format, there needs to be greater emphasize on substantive outcomes, which is not the same thing as policy agreements. Fourth, it needs to be recognized that S&EDs will be fruitful only when certain contexts exist that encourage certain behaviors and deter others, which means more attention needs to be given to shaping the context. Fifth, the S&ED agenda is packed not only with too many issues (more than a hundred), but also too many chronic issues, which reduces the likelihood of meaningful results. Instead, there should be a focus on a subset of key issues where there potential exists for the two sides to cut bargains.

This is not a call for an end to the S&ED. Indeed, it could be very useful if restructured. However, if it persists in its current format – where form rather than substance has become the (acceptable) norm – then it is likely to become self-defeating. Policymakers may become more cynical and disparaging of the other side after repeated S&EDs evidence no new interests, policies or behaviors, but merely restatements of boilerplate text. Publics may read S&ED gatherings less as signs of the ability of China and the U.S. to cooperate, but more as indications that the situation is getting worse. It is time for dialogue about the S&ED, an instrument of declining worth, before it completely loses its value.

Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, Ph.D, is Assistant Dean, School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiaotong University, and Executive Director of the Mr. & Mrs. S.H. Wong Center for the Study of Multinational Corporations. Maya Horin is a graduate student in the Chinese Politics and Economics Program at SJTU SIPA.