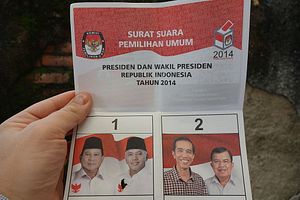

Although the official results of Indonesia’s presidential election yesterday will not be known until July 20, both candidates, Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto, now have claimed victory based on exit polling and quick counts. In the past, such as in previous parliamentary elections, these quick counts have been relatively accurate. But now their accuracy is coming into question. Some of the quick counts appear to show Joko Widodo, or Jokowi, as the winner by around three to six percentage points nationally, while Prabowo claims other counts show him as the winner. Since the race came down to the wire too close to call, it is hard to completely trust any of the quick counts or exit polling. Many election experts have criticized Jokowi for claiming victory too quickly.

The scenario of a disputed election, unresolved even after July 20, now looms for this massive democracy. The run-up to Election Day was full of smears and other dirty campaigning, a far dirtier campaign than the previous two presidential elections; the dirtiness has created a dangerous, angry climate among supporters of both men. Previous direct presidential elections in Indonesia ended with a decisive victory and no post-election standoffs, so Indonesians have little experience with a Bush versus Gore type scenario.

The scenario of a disputed election is a potential nightmare with serious security implications. Prabowo, who has been convinced since he was a kid that he was destined to lead Indonesia, already had suggested before the election, that “losing [the election] is not an option” – he said this in a conversation with a Singaporean reporter. What Prabowo’s comment meant was not exactly clear – it could have been just a rallying cry for his supporters to come out and vote or it could have been the mercurial former general’s conviction that, even if the vote count showed he had lost, he would find some way to still get himself into the presidency. Prabowo, a former special forces and army commander, still enjoys the loyalty of many big business tycoons, of leading Indonesian media networks, and of a coterie of hard-core former special forces soldiers. Were Prabowo to be declared, on July 20, to have officially lost, he could challenge the result through the court system, leaving the country, the most powerful in Southeast Asia, without real leadership for weeks if not months. Indonesia’s highest court is not fully trusted, having endured recent corruption scandals.

Worse, with his network of powerful allies Prabowo could potentially attempt some sort of takeover of the presidency by force if he is declared the loser. This attempt could be a combination of street protests and military actions similar to what has occurred several times in Thailand in the past decade. Although Indonesia’s democracy is far stronger than that of neighboring Thailand, and though the Indonesian military does not appear to be ready to take sides in a post-election crisis, Prabowo’s mercurial nature, and his web of ties to powerful former special forces soldiers, makes such a grab a disturbing possibility.

Joshua Kurlantzick is a fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. You can follow him on Twitter: @JoshKurlantzick. This post appears courtesy of CFR.org and Forbes Asia.