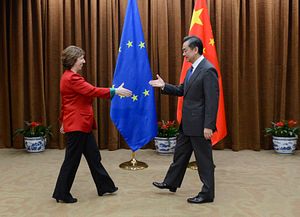

One of the most remarked upon developments of the 2013 Shangri-La Dialogue – a Singapore-based meeting for Asia-Pacific leaders organized by the London-based IISS think tank – was presence of Catherine Ashton. Amid much announcement and noise, Catherine Ashton had flown to Singapore to represent the EU, and not just one of its member states. This was a first for the EU, eager as it is to contribute to the coming Asian security architecture.

The high representative delivered a noted speech, calling on her Asian audience to consider the EU a long-term security partner and expanding on the European’s so-called “comprehensive approach.” Coming on the heels of a number of other initiatives – in 2012, the EU revised its Guidelines on the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy in East Asia, signed the Bandar Seri Begawan Plan of Action to Strengthen the ASEAN-EU Enhanced Partnership, and acceded to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) – the presence and speech of the High Representative signaled the EU’s own “pivot” towards East Asia. The EU appeared committed to strengthening its presence in East Asia, not just in economic terms, but also in the political and security spheres.

This year, the EU was not present at Shangri-La. This absence is not accidental: it sends a clear though implicit signal to both European and Asian audiences that, in times of crisis, the EU is prioritizing other foreign policy issues closer to home than East Asia’s spiraling security dilemma. While not intrinsically good or bad in itself, this position has to be clear if it is to be positively welcomed. Otherwise, it is destined to weigh on the EU’s credibility and status. Mixed signals can have a utility in international affairs but developments in the South China Sea should compel Brussels to better inform its partners of its perceptions and intentions, and, above all, clarify its own strategy vis-à-vis the changing security architecture in Asia and the world.

Missing in Action?

The May 2014 edition of the Shangri-La Dialogue was the scene of considerable diplomatic trepidation. Much had to be discussed after a year of affirmative action by China, keen to develop – as reiterated in October 2013 by President Xi Jinping at a conference organized by the Beijing-based CICIR – “every window of strategic opportunity.”

The most recent in this series of actions was the deployment of Chinese oil rigs in contested waters of the South China Sea, triggering a major spat between China and Vietnam. Bilateral relations, until then thriving, nosedived, with each side accusing the other of provocations and insisting that their respective position was consistent with international law. Sino-Philippine relations also dipped in the wake of multiplying incidents and mutual accusations of misconduct in the South China Sea. These tensions are not just a matter of conjuncture. They follow, and are part of a series of events signaling major and systemic transformations in the parameters of regional stability.

For the last fifty years, Asia’s path to prosperity relied on a fluid security system centered on the United States, falling short of any kind of “Asian NATO.” To date, this system was upheld not just by the U.S. military presence in East Asia and its network of alliances, but also by more or less tacit agreement by other countries, including through China’s “peaceful rise” policy. But with a changing of the guards in most Asian capitals over the last three years and the emergence of Xi Jinping – giving a new, less conciliatory face to the rise of China – things are changing fast.

In this atmosphere, the European absence at the Shangri-La Dialogue was not neutral. Obviously, Catherine Ashton had good reason not to attend. This spring, many developments – including the Ukrainian crisis, enduring instability in the Middle East, and eruptions of violence in Sub-Saharan Africa – contributed to stretch the attention and resources of European foreign policy institutions. But among a pragmatic Asian audience, the discrepancy between the U.S. (the Secretary of Defense explicitly condemned China for undertaking destabilizing, unilateral actions) and the EU (absorbed in its own neighborhood problems) was sharply felt. The presence of the French and British defense ministers did little to alter that.

A Paradigm Shift

Reacting to events without strategic direction would be a dangerous game for the EU. Therefore, to appear as a credible political and security partner, Brussels should embrace the ongoing changes in regional and global power configuration and security architectures. Bypassing East Asia is assuredly not an option. A sustained – increased even – presence in East Asia is necessary in several respects.

First, picturing itself a “long-term security partner” without a coherent and consistent presence will not help the EU much in raising its political and economic profile in East Asia. Words need to be followed by deeds, especially in times of crisis. Visibility in, and commitments to high-level gatherings and summits are important. Second, volatility in the South China Sea requires careful monitoring and attention from the EU, for Brussels has a considerable interest in maritime security there, where a major share of its trade transits. It also requires an adequate response. A concise statement of concern, urging all parties to “undertake de-escalating measures and refrain from any unilateral action […]”, has been issued by the Spokesperson of Catherine Ashton and the G7, but this hardly suffices to demonstrate the EU’s commitment and implication in East Asia’s security affairs.

Third and more important, recent events point to a systemic change in the South China Sea, a shift in the parameters of regional stability that provides a perturbing echo to the Ukrainian crisis. In their closing statement, G7 members confirmed how closely related the Ukrainian crisis and South China Sea issue may be in declaring that they opposed “any unilateral attempt by any party to assert its territorial or maritime claims through the use of intimidation, coercion or force” and calling “on all parties to clarify and pursue their territorial and maritime claims in accordance with international law.”

Until recently, a particular modus vivendi had seemed to have crystallized in the South China Sea. All parties found an interest in maintaining a form of “controlled instability” and strategic uncertainty. This did not require them to clarify their claims, their basis, and the actions they would be ready to undertake to defend them. The DoC and CoC negotiation processes, bilateral consultations, and the defense of UNCLOS have since provided useful – while not too constraining – tools to both contain escalation risks and foster a constructive image abroad.

However, current developments hint at China’s determination to curb the evolution of the regional security architecture in its favor, finding in the growing power asymmetry with its neighbors both the means and legitimating tool to assert a Sino-centric order in the region. A politicized history is here central to China picturing this push to prominence as benign, and resistance to it as provocative. Seen from Beijing, this is only part of a “democratization” of the international system, a “return to normal” after centuries of anomalous domination of the region by other powers. China is increasingly vocal in claiming great power status, and its political elites are leaning ever more towards imperial rhetoric and ambitions. In effect, while the drivers and individuals behind China’s policy in the South China Sea remain ambiguous, its results are tangible. Southeast Asian countries seem increasingly willing to balance China. The U.S. is moving ever closer to its allies, even on slippery slopes such as on the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands issue. And these movements of resistance in turn feed into China’s “siege mentality,” thereby fueling the nationalistic agenda of influent constituencies and government agencies.

What stems from the May 2014 events can be interpreted as nothing less than a new step in a paradigm shift in East Asia. These initiatives pointed to a selective and partial use of international law by parties to the disputes and more worryingly, to the use of national armed forces to ensure that one’s own views prevail. This evolution is explained by the maritime interests and ambitions of parties (and specifically China). For all, stakes are high: the economic resources derived from the sea (hydrocarbons, fisheries, etc.) and those transiting through it are crucial to their economies.

South China Sea sandbanks, reefs and islets have come to embody, in a region bent on fighting the interferences of external powers, the capacity of national governments to stand up for their rights in the face of external aggression, and defend their sovereignty. For China, control of the South China Sea is also a prerequisite to consolidating its access to both the Indian and Pacific oceans and challenge the U.S. Navy. In Kaplan’s words, the South China Sea is for China what the Caribbean is for America: the strategic maritime domain over which they necessarily have to gain control to establish themselves as great powers.

Assets and Options

South China Sea tensions reflect a challenge brought onto norms and conventions underpinnings the regional security architecture. The “rules of the game” that held the region relatively stable up to now have become a divisive issue among regional states. For China, these rules have to change. Xi Jinping even called for a new Asian Security framework at the CICA May 2014 forum (Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building in Asia). To push this ambition forward, Beijing primarily resorts to political pressure, backed by military and economic power. The U.S. has opposed to this a defense of the status quo, relying on political and military resolve, economic integration and diplomatic wooing. The EU is, for its part, largely out of the military equation in the South China Sea, except for its arms exports and some particular initiatives of its members. Nevertheless, it is also an agent of change in the region’s architecture, relying on political dialogue and economic incentives to foster, on the basis of the ASEAN-EU relationship, a rules-based regionalism. This option is, in the European experience and view, the most conducive to both peace and prosperity. In this perspective, it has brought a distinctive input in the security debate.

In other words, what is at stake is whether East Asia’s unfolding new security structure will be forged on an exclusionary (“an Asian security mansion” in Xi’s words) or inclusive basis (with a place for the EU). Even if there is little indication that China’s vision will be realized in the short to medium terms, it is certain that its endgame is to limit U.S. influence in the region and rebalance global security. Very concretely, this would restrict the Asian security dilemma to a Chinese/American face-à-face, implying less room and opportunities for the EU. Europe should thus not remain in the shadow of an uncontrolled power game, but stake out a position with its own assets: a decisive experience in security dialogue and peace-making.

The Shangri-La Dialogue is just one among many forums on politics and security in Asia-Pacific, and certainly not the most important. But it is a comparatively low-risk, highly visible place for policy announcements. A presence would have enabled the EU promote its own added value in the ongoing strategic debate. It would also have been of great help for Brussels to understand the complex dynamics at the core of rising tensions in the South China Sea. There is a price to pay for being a different actor. And this may well be that the EU is little equipped to deal with the challenges inherent to a changing world order, and the realist thinking inherent to Asia’s changing strategic landscape.

It is not too late for the EU to be more involved in understanding and contributing to a changing security architecture in East Asia. Tensions with China may open a door to ASEAN. The Southeast Asian bloc has recently sought to better organize the diverging positions of its members to gain credence as a more united front, the only way to break China’s “salami slicing” strategy (bilaterally deal with each state to avoid a common position among them). In facing the disproportionate military power of China, ASEAN members are simultaneously bolstering their deterrence capabilities, and investing more and more in the legal instrument. On both fronts, the EU has an interest. A former top Vietnamese diplomat recently called on the EU to have a stronger voice and a clearer position on South China Sea tensions. There is room for Brussels to weigh in.

However, what came out of recent developments is also that the EU risks falling between two chairs: a pivot and a look East policy. On the one hand, as Nicola Casarini argued in 2013, “the EU and its member states already began their own rebalancing towards Asia roughly a decade ago. Although this development has gone largely undetected, it could well warrant the label of a European ‘pivot.’” Certainly, when Europe begun to realize how important the Asia-Pacific theater was poised to become in the twenty-first century, it gradually stepped up its engagement of the region. The 2012-2013 period represented a culminating point in this endeavor. But calling this a European “pivot” inevitably makes EU foreign policy fall prey to comparisons with U.S. policy choices. Brussels has long argued that it was seeking a different kind of partnership with Asia than Washington was, based on its experience in the region and economic relations rather than any military presence. Still, terminology does matter, and an actual pivot would require the EU to alter its resources allocation paradigm, and shift considerably more resources to East Asia than it does today.

On the other hand, the crisis in Ukraine has brought Euro-Russian relations back to the fore of Brussels’ foreign policy agenda, and precipitated the EU reinvestment in its Eastern neighborhood. Adding to continued instability in the Middle East and eruptions of violence in Sub-Saharan Africa, this reminded the EU of the volatility of its vicinity. By shifting its attention towards Kiev and Moscow, the EU had not so much rolled back its pivot to Asia as reacted to international developments by prioritizing more proximate and immediate issues. While a pivot to East Asia and an Eastern neighborhood could coexist so far, recent events made this dual approach problematic for the EU. The more Russia tilts towards Asia to compensate for deteriorating relations with Europe, as exemplified by the $400 billion gas deal it just signed with Beijing, the more Europe will have to display a “Eurasian” policy in place of its two disconnected “Eastern” and “East Asia” policies.

In other words, Europe will increasingly have to deal with a geographical and strategic continuum to its East. This “Look East” policy implies the impossibility of actually pivoting to one region or another without prior consolidation of both its neighborhood policies (to its South and East) and transatlantic ties. Either way, there is a choice to make for the EU. And now is a good time.

Sophie Boisseau du Rocher is Senior Research Associate at GRIP and author of “The EU’s strategic offensive with ASEAN: some room left but no time,” Analysis Note, GRIP, January 8, 2014. She has written extensively on security affairs in Southeast Asia for the last 30 years. Bruno Hellendorff is Research Fellow at GRIP’s Asian Desk and author of « Dépenses et transferts militaires en Asie du Sud-Est : Une modernisation qui pose question », Note d’Analyse, GRIP, June 12, 2013 & « Territoires contestés en mer de Chine méridionale ; quels enjeux pour l’Europe ? » , Eclairage, GRIP, June 18 2014 (also published in European Geostrategy here).