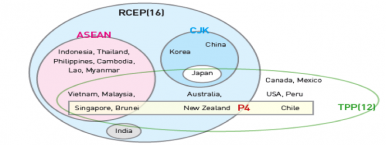

Two massive regional trade arrangements are currently being negotiated in the Asia-Pacific region: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, which would include, among other countries, the U.S., Australia, and Japan, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, with India, China, Australia, Japan and South Korea, among others. Should they take effect, they will likely produce a paradigm shift in the way in which regional trade will be conducted in future.

Participating Countries in Asia-Pacific Regionalism

The TPP aspires to be a high-quality preferential trade agreement with extensive regulatory alignment in many key areas such as environmental protection, labor regulations, and intellectual property rights. In contrast, RCEP members may settle for a modest agreement covering specific issues related to trade barriers along with a limited focus on regulatory harmonization.

Will they pave the way for a new regionalism – Indo-Pacific Economic Cooperation as an emerging concept in economic diplomacy?

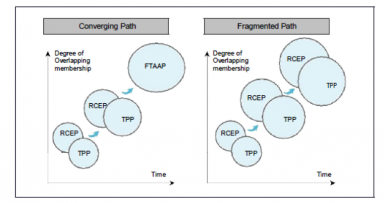

Two scenarios are conceivable. TPP and RCEP may converge into a region-wide, Indo-Pacific free trade agreement (FTA). Or there could be trade fragmentation within the region, with negative consequences such as further trade diversion and disputes. The convergent scenario could produce a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). In the fragmented scenario, there will be further overlapping membership between the TPP and RCEP.

Convergent and Fragmented Scenarios of Asia-Pacific FTAs

Source: Choi Byung-il & Lee Kyounghee, KERI (Future of Trading Architecture in Asia Pacific: TPP vs. RCEP)

Given the large number bilateral trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific, there are multiple tariff regimes and more importantly multiple sets of trade-related regulations and non-tariff measures, such as rules on origin. These increase the cost of doing trade, particularly for small and medium enterprises, and reduce incentives for business to take full advantage of FTAs due to high administrative and compliance costs. In the first scenario, a region-wide FTA could increase the effectiveness of production networks by harmonizing tariffs and non-tariff measures.

The second scenario may result if the U.S. devotes more negotiating capital to the TPP in order to boost its sluggish economy through a trade-led growth strategy, particularly when monetary and fiscal policies are becoming more and more ineffective. Therefore, the U.S. may provide a further push to conclude the TPP agreement at quickly as possible, to boost its economic supremacy in the Asia-Pacific.

China is unlikely to join the TPP talks as its core economic strategy differs significantly from China’s basic tenets. There is a perception within China that the U.S.-led TPP aims to undermine China’s economic might in the Asia-Pacific region. Going forward, Beijing is likely to focus its efforts on an early conclusion of the RCEP agreement.

As Choi Byung and Lee Kyounghee argued in their paper “Future of Trading Architecture in Asia Pacific: TPP vs. RCEP,” which of these two scenarios transpires will depend on a number of factors: the cost of fragmentation versus the benefits of integration, the negotiating interests of participating countries, the domestic political cost of sensitive sectors, and the geo-political rivalry between the U.S. and China.

With Australia and Japan as common members of both the TPP and RCEP, the future trading architecture of the Asia-Pacific region is expected to be a combination of convergent and fragmented scenarios. More importantly, a middle path of new regionalism may emerge out of the Indo-Pacific Economic Cooperation concept. Two recent developments are worth noting: Washington has begun to think in terms of Indo-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and this new term, “Indo-Pacific,” is now in Australia’s foreign policy.

What should India do to convert this new scenario to its advantage? India is the major player in the South Asian region, with average growth more or less on a par with East Asian countries but lagging infrastructure, according to a recent study by the World Bank. This market for new infrastructure, estimated to be worth $1.7 to 2.2 trillion over the next decade, should be leveraged more effectively by India so that it can play a more proactive role in Indo-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

It is right on the part of the Indian establishment to approach future trade negotiations with an eye more on the need for domestic reforms than on trade as a residual economic activity. While negotiating future trade agreements, India should devote more political capital to domestic reforms as that will help it negotiate from strength. In this context, it has taken some encouraging steps to strengthen its domestic trade-related institutions, such as bodies dealing with standards, intellectual property rights, and other such regulations.

Keeping the geo-political importance of the Indo-Pacific region in mind, particularly the triangular axis of India, Australia and Japan, India should be proactive in setting the agenda for Indo-Pacific Economic Cooperation. As a first step, it should be part of the agenda for the next round of India-U.S. strategic dialogue.

Bipul Chatterjee and Surendar Singh are Deputy Executive Director & Policy Analyst, respectively, at CUTS International ([email protected]/[email protected]).