The international community and a number of major Western media outlets have constantly questioned China’s role in the Asia-Pacific region as the country continues its rapid emergence. A popular view describes China as a violator of or threat to the regional order. For example, shortly after China declared an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea, an article in The National Interest talked about “China’s war on international norms” and denounced China’s “unilateral attempt to alter the regional status quo.” Such articles imply that China is a threat to the regional order.

Meanwhile, China has been trying to present itself as a defender of the postwar regional order. For example, during Premier Li Keqiang’s first government work report (delivered to the National People’s Congress in 2014), he included a new reference to China’s determination to “safeguard the victory of World War II and the postwar international order.” More recently, as this Saturday marked the 69th anniversary of the Potsdam Declaration, Chinese media took advantage of the opportunity to revisit the end of World War II and the new regional order that emerged after the war. These reports, like one in Xinhua, describe the Potsdam Declaration as “an important document which helped establish international order after World War II.” The articles argue that Japan is violating the Potsdam Declaration and thus the postwar international order in important ways (for example, by pursuing remilitarization). China’s opposition to these moves, then, makes China a staunch defender of the postwar order.

These differing media analyses from China and the West pose a fundamental question: Is China a threat to or a defender of the postwar regional order in East Asia?

It’s hard to find a definite answer to this question, since China’s rise has been truly unprecedented in terms of its speed and significance. Plus, historical analogies, as fellow China Power blogger Zheng Wang argues, carry inherent limitations and risks. We must not make a hasty judgment and accuse China of being a threat to the current order based on the aggressive moves made by history’s previous emerging great powers. On the other hand, some of China’s actions (like the declaration of an ADIZ) have caused concerns among its neighbors and other great powers in the region, especially given China’s size and geopolitical location.

China’s attitude toward the postwar regional order is rather complicated. However, China’s high-profile commemoration of the Potsdam Declaration provides a window to understand how the Chinese view the present regional order and how they try to defend it.

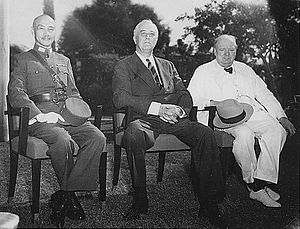

As one of the three signatories (along with Britain, and China), and as the enforcer of the postwar order, the United States originally believed that the Potsdam Declaration (and its restrictions on Japan) helped secure U.S. national interests in the Asia-Pacific. But with China’s rapid rise, things have changed. The Worldwide Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community released by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in January 2014 made it clear that China is regarded as the primary threat to the U.S. in the East Asian region. Washington now believes that the previous regional order and structure (particularly Japan’s role) will not help sustain U.S. regional dominance. Hence Washington’s polices have changed, and today the U.S. actually encourages military expansion in Japan to balance the challenges posed by the rise of China.

Therefore, the Chinese position is as follows: The United States ostensibly tries to maintain the postwar order, but actually intends to make strategic amendments to the regional status quo in order to ensure its continued hegemony. China, though often viewed as a potential challenger or even a threat to the regional order, is actually trying to defend the postwar regional order, particularly with regard to the role of Japan.

Interestingly, this position is not limited to Chinese scholars. In an interview with CCTV, Peter Kuznick, a history professor at American University in Washington DC, also challenged the view that the U.S. is a selfless enforcer of the postwar order He points out that U.S. enforcement of international law came “when it was convenient… but it’s no longer convenient for the United States to hold Japan to those [post-World War II] agreements.” Kuznick continues, “In fact, it is Obama who is pushing much of the worst things that Japan is doing now. Obama is encouraging the Abe administration to rearm, to undermine Article 9, and that’s what countries do in the world of realpolitik. The treaties and the declarations and the agreements often say one thing, and the actions say something very, very different.”

In the above discussion, I don’t mean to imply judgment against China or the United States. Instead, I want to make it clear that the question of “defending the postwar international order” is more complicated that it might appear. In considering this issue, we need to think about both sides, particularly when discussing the role of China and the U.S. in the extremely complex and constantly changing regional situation.