China’s leadership has committed to increasing consumption, and this appears to be taking root. Chinese household consumption has been increasing at a steady rate since the global financial crisis hit in 2008-09, measuring in at $3.15 trillion in 2013. By way of comparison, U.S. household consumption was at $11.15 trillion in 2012, and per capita income in the U.S. is almost eight times higher than that in China. Chinese households therefore appear to be satisfactorily nudging up their consumption.

This increase in consumption is most noticeable in Tier 1 cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, where a relatively young working population, comprising one-child citizens, shops blissfully with friends for recreation. Malls and hypermarkets that were once viewed as entertainment sites for small spending and window shopping are increasingly viewed as destinations for serious shopping and fuller shopping baskets.

Most households continue to earn between $6,000 and $16,000 annually, but a small and growing percentage of the population (dubbed “mainstream” consumers by McKinsey) earns somewhat more than this amount. Many of these mainstream consumers are relatively young and living in large urban centers. These consumers frequently seek more upscale and brand-name items, and shop for goods that show their status and/or individuality.

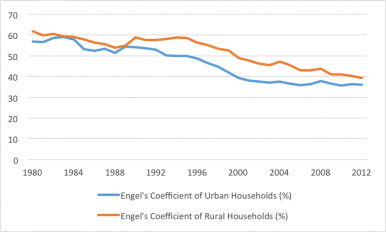

Less wealthy consumers continue to look for quality and value in non-luxury items. As incomes have continued to increase over time, all individuals, including less wealthy consumers, are purchasing less food as a proportion of income (known as the Engel’s coefficient), leaving a larger proportion of discretionary income. Figure One below depicts the decline in the Engel’s coefficient for urban and rural households over time. China’s Engel’s coefficient is only slightly above that of the lowest income quintile in the United States, meaning that all income groups in China spend almost the same proportion of their income on food that less wealthy Americans do.

Figure One. China’s Engel’s Coefficient of Urban and Rural Households (%)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

China’s consumption boom goes even further. An increasing number of consumers are shopping online, with some even using the internet for most of their shopping. Online shopping now accounts for 10 percent of all retail spending, according to China Internet Watch. A growing number of online shoppers purchases foreign goods, which include not only luxury goods such as handbags and clothing, but also regular goods such as baby formula. The purchase of foreign goods is so trendy that it has a nickname, “hai tao.” Many Chinese nationals go one step further and travel abroad in large part to buy foreign products, particularly luxury items that cost more in mainland China.

The Chinese leadership has advocated consumption, and retail space has expanded in step. In 2014, 39 million square meters of new shopping center space is currently under construction, according to CBRE, a real estate services company. Many regions have integrated consumption into urbanization plans. For example, Qingdao, a city in Northeast China, plans to become a center for luxury shopping. The Qingdao Bureau of Commerce has in store for the city the “Qingdao Fashion and Retail Businesses Development Plan,“ to build up a number of luxury shopping malls and retail outlets. Chongqing, a city in the center of China, is planning to build 1.3 million square meters of new shopping space over the next two years. Chongqing’s plans surround the urbanization process that will encompass 14 million rural residents by 2020.

A couple of trends have dampened the general upswing in consumption and successful construction of retail space. These include the crackdown on corruption, which has prevented Chinese officials from purchasing luxury items for themselves or to present as gifts, and the construction of retail centers that have gone empty, sometimes within entire ghost towns. What can be made of these trends, and do they negate the positive pattern in consumer spending that we have seen in recent months?

First, the crackdown on official purchases of luxury goods has taken a toll on consumption. Diageo, a drinks maker, reported a $444 million decline in sales in the fiscal year ending June 30. Most of this decline reflected a sharp reduction in demand for its popular white liquor, baijiu, through its subsidiary company Shui Jing Fang. Diageo is one of many luxury goods companies that has been adversely impacted by China’s anti-corruption campaign. At the same time, China’s mainstream consumers are increasingly aware of, and interested in purchasing, luxury brands. While the anti-corruption campaign has made a dent in luxury spending in the short run, in the long term high-end consumption is unlikely to be affected.

Second, the construction of retail centers that remain empty has occurred in recent years, as lack of growth sources from other sectors prompted government officials to allow a stark increase in fixed asset investment, including real estate development. Many owners of these shopping areas will likely experience heavy losses, as they fail to attract either stores or shoppers. Despite this problem, consumption in hot spots throughout China remains strong. The trend in consumer preferences for shopping locations changes, and has not negated the overall upward movement in consumption numbers.

Real threats to increasing consumption in the long run do exist, however, and have to do with the rate of hukou, or household registration, reform, and the urbanization process itself. The hukou process has long prevented rural residents from permanently moving to urban areas, and the leadership has vowed to reduce hukou restrictions for some. The extent to which this policy is carried out will greatly impact the sustainability of the consumption trend: the rural sector remains relatively worse off than the urban sector, and the hukou remains the biggest formal barrier against urbanization and the associated increase in living standards. Closely related is the urbanization process, which has focused on physically moving individuals to urban areas without ensuring appropriate job creation. By implementing urbanization policies in a superficial way, some regions have raised living standards in the short run without creating the means to sustain it in the long run.

The tide of consumer spending is growing in force, and the leadership does not want to see it end. While the current lag in luxury spending and real estate occupancy may be temporary, serious barriers to building a consumer society remain. Ironically, these barriers are in the hands of the government itself. The policies that are implemented, and the order in which they are carried out, will determine if the ultimate goal of raising and maintaining consumption can be achieved.