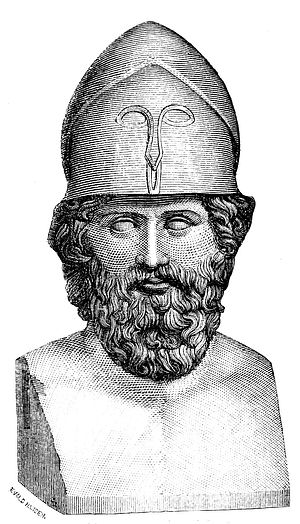

Last week, the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), on online think tank on maritime affairs, published a series of articles on forgotten naval strategists. Posts thus far have included discussion of the Athenian statesman Themistocles, Soviet Admiral Sergei Gorshkov, and Portuguese priest Fernando Oliveira. While no one should take this as an excuse to stop reading Alfred Thayer Mahan or Julian Corbett, it’s well past time to inject different voices into the seapower conversation.

While organized naval warfare has been around for nearly as long as land warfare, it has historically been under-theorized relative to its grounded cousin. A theory of seapower requires, at a minimum, an appreciation that seapower represents a clear and distinct component of national (or imperial) power, analytically separate from general military strength. Thucydides, for example, does not seem to have developed an explicit, separate theory of naval power, apart his appreciation that Sparta and Athens each enjoyed strengths particular to a medium (land in the case of Sparta, sea in the case of Athens).

Part of the problem undoubtedly stems from the practical demands of ship management over the centuries, which has led practitioners to focus more on tacit, tactical issues than grand strategic considerations. On the other hand, naval warfare has always demanded a sustained industrial strategy, in which ships can be constructed, procured, and maintained over extended periods of time. On this point the work of Oliveira is particularly interesting, as his 16th century treatise appears to have synthesized the tactical and strategic issues.

In any case, much of our naval conversation remains dominated by Corbett and Mahan. Both remain vital, but extending the conversation to others is surely a valuable contribution. This is particularly the case given the hegemonic perspective from which Corbett and Mahan are approaching seapower. Both center maritime strategy around big, powerful navies with multiple 19th century-style colonial commitments. For the same reasons that the canon of land power would be incomplete without the works of Lawrence and Giap, the effort to broaden the library of seapower beyond the strategists of empire is long overdue.

All of this may sound distant to modern seafaring concerns in East Asia, but consider; both Gorshkov and Themistocles achieved prominence by building world class navies, virtually from scratch. In Themistocles’ case, this force dominated its maritime world for nearly a century. In Gorshkov’s, the navy disappeared nearly as quickly as it had come together. Consequently, it’s easy to imagine lessons for both American and Chinese authorities. The Japanese, of course, also have some experience with brief, shining moments of maritime prominence. Hopefully, the CIMSEC series will help spur a broadening of the seapower canon.