Sub-Saharan Africa is increasingly within the political and economic sights of South Korean government strategy, a strategy designed to bring some measure of stability to South Korea’s fragile food and fuel supplies. Thus, the decision to send a medical team comprising civilian volunteers and military medics recruited by the Ministry of National Defense to help fight the devastating Ebola outbreak in western Africa could legitimately be viewed as something more than a response to an international plea for help. Rather, despite concerns for the team’s safety, it enhances the Park administration’s push to establish itself as a viable development partner for Africa over China or even North Korea.

This enhancement is arguably more pressing given the response by some sectors of the South Korean citizenry to the Ebola outbreak. It is also a useful offset to concern over the involvement of South Korean ships engaging in illegal fishing, which has driven a perception that South Korean engagement in the region is far from benevolent. According to a recent report, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing has become a serious economic impediment in the region, with South Korea “increasingly being implicated as a lead villain in the growing controversy … (including) its role in dubious fishing policies in waters in East Africa and off the coast of Puntland.”

In August, Duksung Women’s University withdrew an invitation for three Nigerian students to attend the 2014 World Congress of Global Partnership for Young Women there, while a bar popular with both expatriates and Koreans posted a sign saying it was not accepting Africans – “for the moment” – because of the outbreak. Korea’s national flag carrier, Korean Air, also created a fracas announcing its suspension of direct flights to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, Kenya. Such responses did not endear the country to many observers, including foreign envoys.

Also, according to another report, residents in the southern port city of Busan are fearing the government’s preventative measures to fight Ebola are insufficient given that the city is hosting an international conference in which around 140 participants from Ebola-struck West African countries, including some 28 from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. While the fears are perhaps understandable, the irony is that according to a 2011 Gallup Korea survey on behalf of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP), almost 40 percent of Koreans consider sub-Saharan Africa as the most important destination for Korean aid.

Citing Global Humanitarian Assistance, Justine Park at the London School of Economics says, “…in 2010 South Korea gave nearly US$1.2 billion dollars in aid. Sub-Saharan Africa received 47.9% of that assistance; the second largest recipient group was South America with 18.3%.”

The Ebola Aid Connection

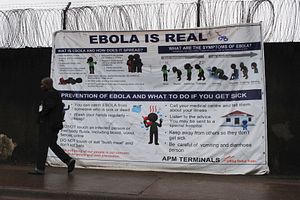

As of October 29 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (WHO) reports a total 13,703 confirmed, probable and suspected cases of Ebola, with 4922 deaths, with Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea accounting for all but 10 of the fatalities, and only 27 cases occurring outside the West African epicenter. The latest country to record an Ebola death is Mali, which shares a border with Guinea.

An October 25 report in The Guardian adds that the “latest report showed a rise of 400 cases in the last three days in Sierra Leone and Guinea but no change in the number of cases and deaths in the worst- affected country, Liberia.”

With the CDC estimating that the number of cases in Sierra Leone and Liberia is doubling every 20 days, possibly reaching 1.4 million by January, that South Korea has agreed to join the fight combating Ebola is without question magnanimous, particularly when countries like Australia are unwilling to do so. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, Australia’s Prime Minister, Tony Abbot has said his government would not send doctors and nurses until it could be “absolutely confident” all the risks are properly managed.

More recently, the Australian government announced this week visas already issued to people coming in from affected region would be canceled and that it would refuse any future visa application until the outbreak is under control. The move has brought “scathing” criticism from Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Perhaps South Korea’s response reflects the fact that for many years it was an aid recipient in its own right and now seeks to continue repaying its international humanitarian debt. It is what a former Australian foreign affairs minister, and head of the Brussels-based International Crisis Group from 2000 to 2009, Gareth Evans, would consider good international citizenship.

From the perspective of proper risk management South Korea is expecting to send an advance team, including government officials, to Liberia or Sierra Leone within the next few weeks to evaluate conditions there and plan for the safety of its medical workers. Interestingly, the South Korean response does not mention the third country where Ebola has hit with severe consequences, Guinea. However, South Korea has so far pledged some $5.6 million to support the fight against the virus.

There is little obvious political or economic gain for South Korea in assisting these two countries. Nonetheless, aside from showing itself as a responsible global citizen, Korea does have much to gain from its decision.

A recently released report “South Korea’s Engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa: Fortune, Fuel and Frontier Markets” by London-based independent policy institute Chatham House suggests that three factors drive South Korea’s engagement with the Sub-Saharan region: “[T]he pursuit of food and energy security, the establishment of new markets for its manufactured goods, and the enhancement of its credentials as a prominent global power, particularly in order to counter the diplomacy of North Korea.”

In releasing the report, Chatham House says, “With a significant upsurge in bilateral diplomatic ties, now with 21 embassies in Africa, and making full use of the weight of its business conglomerates, as well as cultural engagements and development assistance, South Korea has fought hard to raise its profile across the region.” Among their conclusions, the authors say that “[i]n order to facilitate investment, more intensive efforts should be made to promote the more mutual benefits of operating in the region.”

While the Korean government is, according to the report, “currently reviewing its priority partner countries and plans to provide more aid to the least developed, most fragile countries such as Mali in the coming years,” the sending of a medical team to help fight the Ebola outbreak will undoubtedly improve its image in the region.

This is especially important given, “Seoul’s investments in the region have also been tempered by a number of miscalculations. While a protracted dispute with the Nigerian state-owned oil company NNPC served as a stark illustration of the challenges of contract sanctity, the controversy that erupted in the wake of Daewoo Logistics’ attempt to secure vast tracts of agricultural land in Madagascar resulted in a backlash against the country’s Africa strategy.”

Perhaps more significant is the backlash Korea faces over its involvement in illegal fishing within the region.

According to the Chatham House report: “Fishing is the lifeblood of countless coastal communities in West Africa. However, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing has become a serious impediment to the economic development of many states in the region; for example, it is estimated to be costing the impoverished state of Guinea alone $110 million annually, and thousands of potential jobs. Most West African governments lack the capacity and resources to tackle this scourge effectively, and foreign vessels are taking advantage of these limitations. South Korea is increasingly being implicated as a lead villain in the growing controversy over IUU fishing in West Africa, and has recently also been castigated for its role in dubious fishing policies in waters in East Africa and off the coast of Puntland.”

And while it accepts “[t]he much-maligned fishing practices of South Korean vessels in SSA (sub-Saharan Africa) may stem from the fierce competition for marine resources that exists in East Asia…they have irrefutably gained a reputation for particularly aggressive and opportunistic fishing policies in West Africa.”

Such enmity not only arises from the October 2013 transfer of some 4,000 boxes of illegally caught fish from Sierra Leone’s waters into the South Korean port of Busan, South Korean-flagged ships have recently been detained and charged in Liberia for fishing without valid licenses.

The Korean illegal fishing operations in the region are “considered to be extremely well organized” with the industry enjoying “significant political leverage through the use of politically connected agents, particularly in Guinea.”

The Chatham House report also indicates the South Korean ships have been identified as “the key culprits in illegal fishing both inshore and deep offshore in West Africa, and are now viewed as being the main aggressors by fisheries authorities in the region – particularly in the inshore coastal waters between Ghana and Guinea.”

South Korea’s involvement has become so severe that last November the EU issued a “yellow card” to Korea for falling short of its obligations in the fight against such practices. Korea’s failure to ensure the implementation of fishing policy reforms could see the EU forbidding its 28 member countries from importing fish from South Korean vessels, a trade worth around $100 million a year.

Back to Africa

As far back as 1999, the OECD said Africa has the potential to become an agricultural superbloc if it could unlock the wealth of the savannahs by allowing farmers to use their land as collateral for credit. And while South Korea is not alone in recognizing this potential, its relationship with Africa is a little studied area in contemporary development literature.

Nonetheless, South Korea’s interest in Africa dates to the 1960s and 1970s, when it sought political recognition and attempted to counter North Korea’s influence on the continent. At the time, North Korea had 23 embassies in Africa, while South Korea had just ten.

“Thus, Seoul’s motivation in the early years focused on establishing diplomatic ties to compete with North Korea” ultimately helping Seoul secure UN membership in 1991, after which “Seoul’s relations with Africa stagnated, seeing a decline in the number of embassies and consulates in the region, according to Senior Research Fellow at the Korean think-tank Re-shaping Development Institute, Soyeun Kim.

She also says “[l]ike many other emerging actors rushing to Africa” Seoul aims to diversify and secure supplies of raw materials and resource supplies, and expand its export markets, a point expressed in the Chatham House report.

With two successive administrations under Roh Moo-hyun and Lee Myung-bak playing major roles in (re)cementing Africa’s place in Korea’s foreign policy considerations, a question facing the Park administration revolves around its motivations to dispatch medical teams to help fight and contain the spread of Ebola.

Given South Korea imports up to 90 percent of its food requirements and is forced to import 97 percent of its primary energy demand is it a decision driven by a politically expedient national interest or is it purely altruistic?

Is the decision to send medical teams to been seen in the same tenor, despite the government saying in January it will increase this year’s aid for developing countries, with around 0.16 percent of Korea’s gross national income, some 2.27 trillion won ($2.14 billion), being earmarked for official development aid in 2014?

Is the Park administration facing the conflict as Eun Mee Kim and Ji Hyun Kim describe in their working paper South Korea’s Official Development Assistance Policy Under Lee Myung-bak: Humanitarian or National Interest? “Korea struggles to find its global image amidst the tension between being an aggressive economic power versus a globally responsible citizen.”

After all, as the Chatham House report indicates:

“South Korea’s status as an advanced industrialized economy means that it can ill afford to neglect relations with a region of almost one billion people that is growing in both economic and demographic terms. The political economy of South Korea has brought new challenges for its government, which has in turn brought about a renewed sense of urgency in terms of engagement with Africa. The necessity of safeguarding food and energy security, the need for access to new export markets and the desire for political influence have all driven it to employ a variety of instruments in pursuit of these goals.”

Chris Brockie (ROK Freelance) is a former Australian journalist and news bureau chief now working out of South Korea where he has lived since 2001.