As I pointed out last month, the Smithsonian Museum’s Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. is home to an excellent variety of Asian and Middle Eastern themed exhibitions, with new and unique features almost every other month. This month, the museum began the display of a new exhibition called Unearthing Arabia: The Archaeological Adventures of Wendell Phillips.

Wendell Philips was an American archaeologist who explored the ancient cities of South Arabia (mostly in today’s Yemen) and has often been called the American “Lawrence of Arabia.” The exhibit focused on his archaeological work between 1949-1951 in the ruined cities of Timna and Marib and later work done by his sister at Marib that began in 1998 but has been discontinued due to recent conflict. The story of Wendell Philips is an interesting one in and of itself.

In the early 1950s, Phillips and his team fled Marib due to political unrest. At that time, Yemen consisted of the northern Kingdom of Yemen, also known as North Yemen and the southern British-run Aden Protectorate, the precursor of South Yemen (the two Yemens united in 1990). The Kingdom of Yemen was especially notorious for its lawlessness and tribal feuds. Philips excavated Timna in South Yemen first before crossing over into North Yemen to excavate Marib. However, he soon had to flee due to tribal harassment and was never able to return. During his time in Yemen, he had numerous adventures and became the only American to be made a Bedouin Sheikh. Later on, after he had left Yemen, Phillips used his Middle Eastern connections to get into the oil business. At the time of his death in 1975, he had more oil concessions than any other individual holder in the world, valued at $120 million.

Although Phillips was initially interested in uncovering more information about the fabled Queen of Sheba, his work did a lot to shed light on Pre-Islamic South Arabia and the incense routes that made the region wealthy in ancient times. South Arabia grew prosperous around the time of the Roman Empire, and was at the height of its civilization from the eight century BCE to the second century CE. Its prosperity was due to its location midway along the spice route between India and the Mediterranean as well as from its near monopoly over the incense trade. Additionally, South Arabia is mountainous and can support a large, agricultural population unlike the rest of the Arabia Peninsula, which is mostly desert. As a result, South Arabia developed the oldest and most advanced Arab civilizations of the ancient world. Today, modern Yemen has almost the same population as Saudi Arabia, which is many times larger than it.

The main incenses of the ancient world were frankincense and myrrh, both derived from tree barks mainly found in South Arabia. Incense was extremely important in ancient times where it served essential religious and secular purposes. It was used extensively in the worship of various Near Eastern, Greek and Roman gods. Additionally, incense had an important practical purpose. According to Phillips, “today we can scarcely appreciate the role of incense in the ancient world because, for one thing, it is difficult to imagine the odors of that world, requiring clouds of sweet-smelling smoke to cover them.”

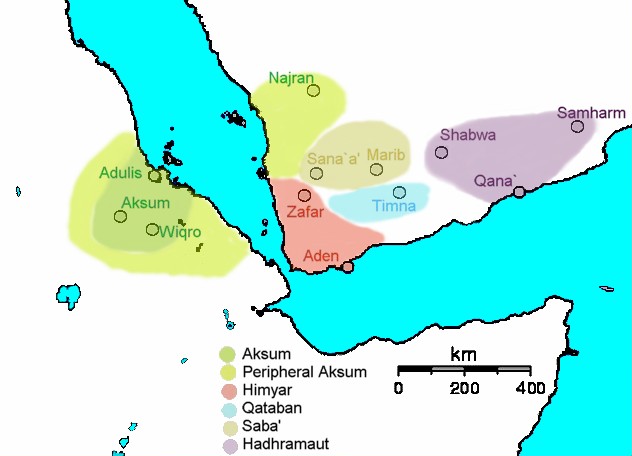

There were several ancient South Arabian kingdoms which grew rich off of the incense and spice trades. These included Qataban, of which Timna was the capital and Saba, also known as the Sabaean kingdom. This kingdom is the likely location of Sheba and its capital was Marib. There were five kingdoms in total during this period, the other three being Ma’in, Himyar, and Hadhramaut. At Timna, Phillips discovered a temple to Athtar, the local love goddess. Outside of Timna, Phillips discovered a small oasis customs town that brought further wealth to Timna called Hajar bin Humeid. Qataban was said to have monopolized cinnamon routes in addition to trading in incense, the wealth of which was used to build 65 temples. At Marib, Phillips’ team began to unearth the largest temple found in the Arabian Peninsula, the Awam Temple, also known as Mahram Bilqis. Inscriptions from the temple tell us that it is the temple of Almaqah, the mood god who was the principle deity of Marib. The temple contained a “large hall lined with monumental pillars, stairways, impressive bronze and alabaster sculptures, and numerous inscriptions.” Although the architecture of all the buildings discovered in both sites was typically Arabian, there were Persian and Greco-Roman influences and many of the artifacts found at both sites were clearly inspired by Greco-Roman art.

Eventually, however, the South Arabian kingdoms declined and fell due to economic and political upheavals, both in their vicinity and further away. Cultural shifts in regards to incense and new trade routes also contributed to its decline. The region never became as important was it was during ancient times, though it partially reinvented itself as the hub of the coffee trade during the late Medieval period. The work of Phillips helped lay the groundwork for future work by his sister whose team generated maps and diagrams that will help in the future excavation of sites like Marib or other sites in the region. Unfortunately, many sites in the Middle East cannot be currently excavated or are in grave danger due to continuing violence in the region. It is important that governments and organizations continue to emphasize the importance of archaeology, including the possibility of commercial tourism, so that there is incentive to continue excavations with support and protection. The Middle East is extremely rich in ancient sites and heritage and it would be a pity if its antiquities and ruins are neglected or lost.