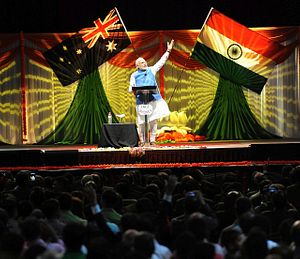

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently concluded a highly successful visit to Australia. Not only did he take part in the G20 Summit in Brisbane this week, but – in a typical Modi move – he added a state visit. It was in fact the first visit to Australia by an Indian prime minister in 28 years.

Given the great potential in the Indo-Australian bilateral relationship, the long gap between visits is hard to fathom. India and Australia today both have significant roles to play in maintaining peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific, even if as part of the U.S. “pivot.” Australia is also part of Modi’s “Act East” policy push and this visit follows close on the heels of his recent engagements with the likes of Japan and Myanmar. But his outreach to Australia is about much more than just geopolitics.

There are several economic sectors where India needs Australia: agriculture, for instance – a sector that still employs more Indians than any other. For a developed country, farming still represents a fairly significant percentage of Australia’s GDP; at 2.4 percent it is twice the level in the United States. When value-added food processing is included, the figure is much higher, at about 12 percent. Food processing is an industry with great potential in India, given its large agricultural output every year. Yet, its share in the country’s GDP is less than 7 percent. India’s food processing industry suffers from chronic inefficiencies and mismanagement. New Delhi hopes that Australian investment in the sector can bring quality and innovation while also increasing employment.

If agriculture is a key employer in the Indian economy, it is also a terribly inadequate earner. Productivity issues, due in part to erratic monsoons, have sent prices soaring in India, even as farmers in different parts of the country see dwindling returns. Much of this has to do with poor irrigation and outdated farming techniques – both of which, incidentally, are Australia’s great strengths. Australia’s great prowess in productive farming has helped turn a country famous for its deserts into a leading agricultural exporter over the years. India could benefit significantly from technology sharing with Australia in making its farming sector more productive.

Then, of course, there is the energy sector. India is today among the world’s most promising consumer markets. But it’s woefully short of energy. A third of Indians today live in darkness. In 2011, India used more than 600 kg of oil equivalent energy per capita. That was less than a third of what the average Chinese consumed the same year. This wasn’t because of a shortage in demand; it was due to a shortage in supply. This is where the bilateral partnership holds the most promise. Australia is home to the largest uranium reserves on the planet, with nearly a quarter of all of the world’s uranium. Until recently, Australia had a ban on selling uranium to India because of New Delhi’s non-ratification of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). That ban was overturned by the previous government in Canberra, before Prime Minister Abbott finally sealed a deal on the issue when he visited New Delhi this September. New Delhi hopes that the uranium deal will help it gain some breakthroughs in the Indian energy sector.

Another avenue for collaboration is in the higher education sector. India’s ability to make use of its demographic dividend depends on the quality and reach of its education sector, primarily higher education. That sector still leaves much to be desired. Many Indians seek education overseas because of the lack of quality at home. In 2013 alone, more than 4,000 Indians applied to Australian universities – compared to fewer than 2,000 the previous year. But New Delhi seeks to give its students greater opportunity back home. Australian investment in Indian higher education, perhaps even through setting up branches of Australian universities in India, will be a great aid in that plan. It was no surprise then that among the first people Modi met on landing in Brisbane were scientists and students at the Queensland University of Technology.

The potential in the Indo-Australia partnership, then, is tremendous. New Delhi and Canberra have multiple areas of potential collaboration. In India’s growing middle class, Australia has a potential market. India, for its part, stands to reap benefits from Australia’s knowledge economy. The exchange has just begun.

Mohamed Zeeshan is a student of engineering at VIT University, India and a commentator on issues of Indian and international governance.