Professor James Holmes recently wrote (yet another) excellent article on the nature of naval warfare, supporting Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel’s remarks on land-based coastal defences. Hagel has been widely derided for referencing the War of 1812 as an example of why land-based defences are still valid military assets. In fact, if one leaves the Western Hemisphere and looks to Northern Europe, there are several examples of how coastal fortifications, even with inadequate weapons and supplies, were able to significantly affect military operations during WWII. Finnish coastal artillery was able to severely hamper Soviet naval activity during the 1939-1940 Winter War, aiding in the prevention of a dreaded amphibious landing behind the overstretched Mannerheim Line. Moreover, coastal forts on the Karelian Isthmus were able to turn their guns on advancing Soviet ground forces with great effect, in effect becoming the most powerful and accurate land-based artillery of the war.

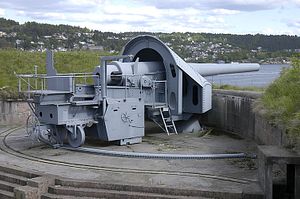

However, perhaps the most decisive use of coastal artillery in Nordic waters occurred during the German invasion of Norway on April 9, 1940. In what has become the stuff of Norwegian military legend amid an otherwise underperforming campaign on the part of the Norwegian armed forces, an undermanned coastal fort in the Oslo Fjord was able to sink the German heavy cruiser Blücher and damage the Lützow with the loss of around 1,200 crewmen. When asked whether the antiquated batteries should open fire on the approaching unidentified warships, Norwegian Colonel Birger Erichsen famously stated “Either I’ll be a hero or a criminal. Of bloody course we’re to fire with live ammunition!” This action delayed the German occupation by several hours, allowing the Norwegian Government and Royal Family to eventually evacuate to London and continue the war in exile. Norwegian forces were encouraged to continue to resist the German invasion until allied forces could arrive, which culminated in the Norwegian-Allied victory in Narvik two months later, representing the first large defeat suffered by German forces on land during WWII.

But wait. In the age of long-range precision bombing and high-altitude air strikes, one might argue that there is little use for old-fashioned, stationary coastal forts like the ones that saw action during WWII. While this is true, the nature of land-based coastal defence has change. During the Cold War, the Norwegian and Swedish militaries trained small and mobile units of rangers and marines armed with small, but effective precision weaponry to counter Soviet amphibious landings along their long and rugged coastlines. Even if these attacks could not defeat a large-scale invasion by themselves, they would damage and delay high-value ships operating far from repair facilities and logistic support.

What lessons does this offer for the 21st century? Well, for a start, mobile, land-based coastal defence is especially useful as an asymmetrical tactic for a weaker belligerent fighting in its home littorals. This fits well into an A2/AD strategy a smaller state worried about being invaded might employ. Training, equipping and deploying capable land-based coastal defence unit is more cost-efficient (if less prestigious) than deploying a large navy in order to control offshore waters. Second, it is most effective if it takes advantage of rough terrain and weather. Finally, it can be an effective delaying tactic as a part of a wider defence strategy, especially if the defender is waiting for aid from abroad. By coastal defences’ very presence, an attacker might have to reconsider where it should land its invading forces.

Taiwan, anyone?

Benjamin David Baker is an advisor at the International Law and Policy Institute, a private research institute and policy advisory based in Oslo, Norway. He is currently serving as a reserve intelligence officer in the Norwegian armed forces.