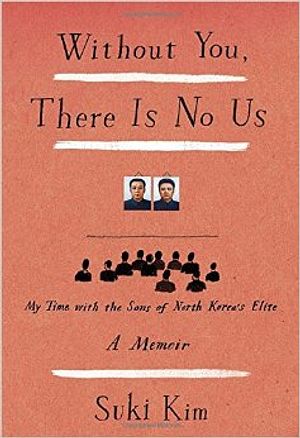

Suki Kim, author of the award-winning novel The Interpreter and recipient of multiple fellowships including a Fulbright Research Grant and a Guggenheim Fellowship, spent six months in 2011 teaching English at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (PUST), North Korea’s only privately funded university. The university is staffed by foreigners and exclusively teaches the sons of North Korea’s elites. Kim’s recent memoir, Without You, There Is No Us; My Time with the Sons of North Korea’s Elites chronicles her stay in the country and sheds some light on the lives of the young men she taught.

Many first-hand accounts of life in North Korea come from defectors who, as Kim notes, tend to be poorer and from the far north, along the Chinese border. In any case, their perspectives are narrow. High-level defections are rare and knowledge of how the upper-crust lives is equally scarce. Other views of life in North Korea stem from carefully orchestrated events – such as the New York Philharmonic’s 2008 visit. Reporters allowed in for such events are herded through a choreographed experience, like tourists sitting through the It’s a Small World boat ride in Disney World.

In 2008, Kim was assigned by Harper’s magazine to go to Pyongyang with the New York Philharmonic. “Not being a real journalist – at least I did not consider myself one” she writes, “I dreaded the prospect of covering the DPRK alongside so many veterans, until I realized how little they knew of North Korea, and how little they managed to find out.”

Without You, There Is No Us is a perfect analogy for North Korea: you always only get half the story, are constantly reminded of George Orwell’s 1984, and the chances of reunification seem to be zero. Although Kim has come under some criticism for her methods – the president and founder of PUST has denounced her for breaking a promise, which she maintains she did not make, to not write about her experience – Kim’s deceptions in gaining access to North Korea are small sins.

Kim has penned a response to criticism of her methods. The core of her counter is that it is disingenuous to criticize her while ignoring the markedly larger sins of the North Korean state.

“The gist of the negative emails and Twitter messages that I have been receiving seems to be that I have blood on my hands. I disagree. The blood, I believe, is on the hands of all of us who sit back, debating the moral guidelines of journalism, waiting for North Korea’s permission to tell North Korea’s truth according to North Korea. There are so few unfiltered portraits of life inside North Korea, and our understanding of this brutal nation remains dismal.

Meanwhile, in the six decades since Korea was divided, millions have died from persecution and hunger. Today’s North Korea is a gulag posing as a nation, keeping its people hostage under the Great Leader’s maniacal and barbaric control, depriving them of the very last bit of humanity.”

Deception is a central theme in both Kim’s book and the reality of life in North Korea. Unlike the North Korean state, Kim is upfront with her own deceptions. “It was a mystery to me,” she writes, “why I had been allowed in.” She applied for the position at PUST using her real name. A quick Google search would have revealed Kim as a writer who had published numerous articles about North Korea. But even her students, who were technically computer science majors, were unaware that the intranet they used was not the global Internet.

While Kim repeatedly states in her book that she fell in love with her students she also comes to doubt and fear them. She becomes acutely aware of the lies her students tell. Some are small, clumsy lies. The lies children tell. At one point a quarter of her class tells her they had accidentally left their homework in the dormitory. She asks them to go get it, but they demur. Eventually they admit they have not done the assignment.

This is not a single student claiming that dog ate his homework; the students lie en masse. In one instance, a student is missing from lunch. Kim asks where he is. Two students speak up at the same time: One claims the missing student has a stomachache, the other says he’s gone for a haircut.

“A few minutes later, I saw the allegedly sick student playing basketball, seemingly unaware that his classmates had covered for him so fervently. It dawned on me that it was entirely possible he had no idea. I realized that the whole group had noticed he was missing and immediately filled his place at my table and made up an excuse for his absence. There was something touching about such fraternity, but at the same time, the speed with which they lied was unnerving.”

Ultimately, Without You, There Is No Us is a valiant effort to humanize a society shrouded in darkness, both figurative and literal. Kim delves into that darkness with a personal touch lacking in most coverage of the peninsula. Although Kim is mostly successful in portraying her students as real people, the Orwellian nature of North Korea is always creeping in at the edges, tempting you to wish it were all just dystopian fiction.

Catherine Putz is the special projects editor at The Diplomat.

Read our interview with Suki Kim in the January issue of The Diplomat Magazine.