Reports released by the IMF and the World Bank’s International Comparison Program show that, when measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), China overtook the U.S. to become the world’s largest economy before the end of 2014. A recent article by Nobel Prize winner Joseph E. Stiglitz claims that the “Chinese century” has begun and that Americans should take China’s new status as the number one economy as a wake-up call. Before crowning China as the new world leader, however, we should consider three questions. First, is China really the world’s largest economy – and if so, why is China so uneasy about the reports that make that claim? Second, has the “Chinese century” really come? To use international relations (IR) jargon, have we seen the beginning of a true power transition between the U.S. and China? Third, does China mean to challenge the U.S. through its recent diplomatic and military moves? A related, though broader, question is simply what kind of international role does China truly seek?

Let’s first look at why China generally dislikes the reports that claim China is now the world’s largest economy when measured by PPP. The general belief is that China is trying to avoid the costs that come with accepting a new role as number one. As Stiglitz points out, these potential costs include “paying more to support international bodies” and increased pressure “to take an enlightened leadership role on issues such as climate change.” In addition, China may be wary of the U.S. reaction to the change.

However, there are counterpoints to these arguments. For one thing, China holds a rather positive attitude toward international bodies and its involvement in intergovernmental organizations has been rising in recent years. Take U.N. membership dues as an example. From 2006 to 2007, China’s U.N. membership dues increased by 42 percent. When it comes to the overall share of membership dues, China’s share has risen from 2 percent in 2005 to 5.1 percent in 2014, more than doubling in less than ten years. Interestingly, the country that owes the U.N. the largest sum of dues is the U.S., which had unpaid assessments totaling over $800 million in 2014.

As for China being wary of leadership on climate change, that too is changing. During the U.N. Climate Summit in 2014, China voluntarily pledged to reduce its carbon intensity by up to 45 percent from 2005 levels by 2020. And when it comes to America’s psychological preoccupation with being number one, China does not need to constantly worry about unspoken messages from the U.S. That’s certainly not the leadership style of the Xi Jinping administration.

So why has China been so reluctant to accept the findings? That requires returning to our original question — does China truly count as the world’s largest economy? According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China’s total GDP for 2014 reached 63.65 trillion RMB (or $10.4 trillion). That’s still only 58 percent of the U.S. GDP for 2014. Given this fact, China has issues with the credibility and applicability of the PPP statistics. Ma Jiantang, commissioner of the NBS, explained these issues in a Beijing press conference held on Tuesday, questioning both the choice of goods for determining relative pricing and the applicability of such price comparisons. PPP concerns aside, there is still the undeniable fact that no matter how enormous China’s economic output is, it must be divided, not by 126 million (the population of Japan) or 315 million (the population of the U.S.), but 1.3 billion.

Because China does not put much stock in the PPP calculations, it has not embraced the claim that it has the world’s largest economy. In Chinese media, the situation is described as China “being ‘number-oned’” (被第一), with China as a passive actor having the role placed upon it. Does China want the illusory honor of a not-very-credible status as the world’s largest economy? Those who truly understand China should know that the answer is no. The PPP statistic may make for some intriguing headlines, but don’t take it too seriously.

So, if China is not the world’s largest economy, what to make of the so-called “Chinese century”? There’s enough evidence to prove China’s ever-growing diplomatic confidence or even assertiveness, particularly as China extends its economic power and military capacity to far-flung regions such as Africa and South America. The question is, does this imply a “Chinese century” in a meaningful sense? After all, China is not the only country seeking to expand its status; Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi also claims that the 21st century belongs to India.

As the U.S. still remains the only superpower and maintains its superior leadership in most world affairs, we need a more cogent definition of the “Chinese century” than simple exclamations over China’s ever-growing economic power. Viewed through the lens of power transition theory, the truth is that China has yet to reach power parity with the U.S., which (according to Ronald Tammen and company) comes “when a great power becomes a potential challenger and develops more than 80 percent of the resources of the dominant nation.” We’re not there yet, although sooner or later China will probably reach that point based on its huge (but aging) population, its high economic growth rate, and the size of its economy. Still, the genuine power transition is yet to come. Besides, keep in mind that power and leadership are very different concepts in world affairs.

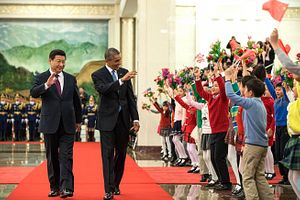

This brings us to the third question: does China mean to challenge U.S. leadership with its seemingly bold moves? Chinese analysts will likely answer this question with another question: how does the U.S. view and deal with the rise of China? As a matter of fact, the U.S. has a mixed and sometimes very ambivalent attitude toward China’s rapid emergence, and its view on China has often wavered. Since 2000, we’ve seen China described as a “strategic competitor” by George W. Bush when he first took office, then as a potential “responsible stakeholder” (a model suggested by former Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick), and finally as “neither our enemy nor our friend,” according to Obama in a 2007 presidential debate.

Meanwhile, China has a relatively firm and clear stance for its American policy. Though the terminology has shifted from “constructive cooperation” under Hu Jintao to the “new type of great power relations” advocated by Xi Jinping, the theme has always been seeking common ground while reserving differences. These different approaches to the relationship determine how each side views China’s recent moves. China regards its behavior as normal, necessary, reactive, and sometimes even compulsory, while the U.S. quite often believes that China intentionally makes troubles and intends to challenge U.S. leadership.

What kind of international role does China truly seek? Does it intend to challenge the U.S. by utilizing its ever-growing economic power and military capacity? Does it want so badly to be the world’s largest economy, even when measured by PPP? I’ll answer by way of a simple metaphor. We need clothes throughout our lives, to protect our bodies. Yet from childhood to adulthood, the size and style of our clothing constantly changes to meet the needs of ever-growing bodies. In this metaphor, international rules are the clothes, and China is the ever-growing body. China needs the “clothes” – that is to say, China’s emergence should fit into the international environment and its various rules. International rules play an important regulatory and custodial role. However, the “clothes” are being outgrown – they need to be altered. China’s inclusion in the international system should be an interactive and reciprocal process, where both sides make necessary adjustments.

This does not mean that China demands hegemony. What China truly wants is a peaceful and stable neighboring environment and particularly mutual respect. This is not vague rhetoric, but the very core interests of China.