Allegedly, Russia invaded Ukraine because Russians and Russian speakers there were in danger of losing their cultural-political rights to a supposedly neo-Nazi, Fascist government there. Of course, these charges were wholly mendacious. But they do highlight the salience of Russian language use in the countries of the Russian diaspora of the former Soviet Union as having a direct bearing on the security of those states. Indeed, a 2009 Russian law that Russian President Vladimir Putin directly invoked to justify the invasion of Crimea permits the Russian president to order troops into other countries to uphold the “honor and dignity” of Russians and Russian speakers if it is being violated. Given that, it should be clear that linguistic policy in Central Asian countries is a matter of the utmost importance, requiring considerable subtlety on the part of Central Asian leaders.

Nevertheless it has been clear for some time, and recent news reports confirm it, that the Russian language is steadily losing ground in Central Asia in educational institutions and in much of the media throughout Central Asia. To be sure, Moscow is trying to counter this, for instance with recent attempts to saturate the Kazakh media. Yet this trend towards establishing the primacy of national cultures and languages at the expense of Russian builds on twenty years of steady nationalization of the culture of these states as a matter of deliberate policy, on their deliberate efforts to maintain an openness to the larger globalizing trends in the world economy, and on a generation of growing restrictions on Russian language use in broadcasting and other media.

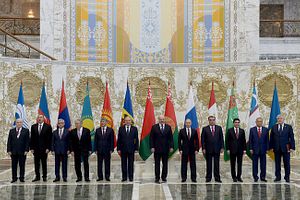

Of course, Central Asian leaders will not publicly attack the use of Russian language or create situations that could tempt Moscow to intervene in Central Asia on the same pretexts as it employed in Ukraine. But while the invasion of Ukraine created and still generates considerable anxiety in Central Asia, the crisis that Russia faces as a result of its action makes intervention in Central Asia a less likely prospect for the foreseeable future. Given the steep economic decline Russia has experienced following its Ukrainian adventure a third front on top of Ukraine and the North Caucasus is the last thing Moscow seeks. Nonetheless, leaders like Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev point with pride to the growth of Kazakh as the native language and more younger students are preferring English or Chinese to Russian.

In Kyrgyzstan, a recent report showed different forces at work but similar outcomes. The poverty of the Kyrgyz school system means that despite Russian claims of large-scale support for Russian-language teaching abroad, means that only 11 percent of Kyrgyz students are going to superior Russian schools in that republic. Students otherwise are not learning Russian and competent teachers are hard to find. All this, of course, generates a vicious cycle. Similarly, in December 2013, Veniamin Kaganov, Russia’s deputy education minister, was quoted in Tass as saying that the number of Russian speakers had fallen by 100 million since the break up of the Soviet Union. Neither is this outcome unique to Kyrgyzstan or Central Asia. Although globalization certainly plays a role here, all these states have taken serious policy steps since 1991 to create a stronger sense of national identity among their peoples, a policy line that inevitably translates into privileging native languages over Russian and English and now Chinese over it as well.

This outcome strongly suggests that while state support for the propagation of he Russian language abroad is a point in Russia’s 2009 national security strategy, Moscow is apparently steadily if somewhat unobtrusively failing to achieve its goals. And this testifies to a continuing failure to actualize Russia’s soft power despite an enormous state investment. The manifestations of this failure may be quiet and not immediately visible but they do point to the steady erosion over time of Russian power of all kinds in Central Asia, although its military capabilities there remain potentially formidable.

Moreover, Central Asian states have proven to be rather more adroit that was expected at defending themselves against Russian encroachments. Nazarbayev even publicly threatened to leave the Eurasian Economic Union, the centerpiece of Putin’s grand design when Putin made threatening statements about Kazakhstan’s former lack of statehood. Similarly, in Uzbekistan a 2013 decree by President Islam Karimov mandated the teaching of English in first grade and Russian in second grade, a sure sign of his priorities and that of the state. Non-Uzbek schools in the republic, Tajik, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh have also cut their teaching of Russian while increasing English language instruction. Thus the Russian language is steadily being marginalized in Uzbekistan as well.

It is by no means clear what Rusisa can do about this. Its economy, even before the recent sanctions and crisis, was sputtering and its record of follow through on implementing its grandiose decrees and plans is quite poor. Moreover, these states are clearly determined to ensure and consolidate the primacy of the native language narrative across all dimensions of its use and to defend their national security and integrity to the fullest short of war. Moreover, it is quite clear that Russia, even at its best times, lacks the capacity to deploy soft power on the requisite scale in Central Asia and win the support either of the local governments or the population. In some states, such as Turkmenistan, migration back to Russia has long since begun because of an increasingly inhospitable socioeconomic if not cultural environment. So while Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan will not directly challenge Moscow here, they will proceed by other means to strengthen their own national identity at the expense of the past Russian supremacy in culture and politics. Russian culture will hardly disappear anytime soon from Central Asia but it is steadily losing ground and will increasingly be more of a historical relic than a working alternative except in certain specific environments. English and Chinese, especially as China keeps building Confucius Institutes and consolidates its primacy as Central Asia’ main commercial partner, will displace Russian. And increasingly it appears that under the circumstances there is not much Moscow can do about it.

Stephen Blank is a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.