“Everyone under 18 has only one guru, Google guru,” said Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a Nasscom event in early March. He insisted that India’s IT industry, where innovation plays a critical role, is successful because government is “not there anywhere.” By implying that state participation stifles industry growth, this widespread sentiment belittles industrial planning and the promotion of particular sectors or corporate champions. Does Modi’s statement about the absence of government support India’s commitment to R&D and innovative capacity? Innovation is a driver of national competitive advantage, and ultimately the individual is the primary source of innovation. Therefore, connecting human development and government intervention becomes a crucial task in supporting growth strategies.

Following India’s latest budget, and amidst mixed messages about the country’s 2015 economic prospects after a disappointing 2014, discussions have focused on governance failings in typical areas such as corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, the growing infrastructure deficit, and an underperforming education and academic research sector. Some analysts argue that a burdensome corporate tax rate (falling from 30 percent to 25 percent under the new budget) and inadequate fiscal incentives are discouraging investment and innovation. Others cite intellectual property protection as a key condition for innovation. Strikingly, India ranked 29 out of 30 countries (ahead of only Thailand) in the 2015 Global Intellectual Property Center index, which measures commitment to innovation via IP protection efforts. India ranked last in the two prior years.

Such an array of causes for India’s economic woes would bewilder even the most seasoned policymaker. How, then, can these causes be specified and linked to policy remedies, particularly in the innovation-driven global economy? Prominent Indian businessman Satish Reddy recently bemoaned that the latest budget makes only modest appropriations for innovation. By contrast, infrastructure spending is slated to increase, with a more robust focus on public-private partnerships. Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) scientist Prakash Mujumdar argues that India’s efforts to boost innovation should include expanding broadband infrastructure, encouraging more students to pursue science-related fields, and fostering a culture of experimentation.

Mujumdar’s last point is a critical factor distinguishing innovation-poor countries from innovation-rich countries. The latter provide a possible roadmap for India’s development, but the synergies of multi-faceted policy interventions are elusive without systemic cultural reform at both the organizational and individual levels. Such innovative cultures are already present in many developed countries, and India can realistically aspire to similar.

A common policy trap involves capital therapy, namely the assumption that additional money will successfully address challenges. For example, V K Saraswat, member of the Indian think tank NITI Aayog, identifies R&D spending as a key factor in India’s pursuit of growth. Yet R&D spending in India has grown by double-digit percentage points in recent years while innovative capacity lags. This highlights a glaring disconnect. Innovation is not a metric in which one country or firm can simply out-spend the other. While technology, infrastructure, and governance are necessary for innovation, the global competitive environment cannot be reduced to a military-style arms race. Innovation is about culture and this is a factor over which government has only peripheral control.

India has introduced a National Skills Council to oversee worker education and vocational training. There is a measurable link between innovation and worker productivity, and recognition of individual innovation is not entirely absent in India. National cultures of innovation and entrepreneurship may be regarded as complementary, and in some emergent ways Indian firms are embracing innovation as an operational strategy and institutionalizing innovation in the workplace through dedicated corporate roles. However, such initiatives may not be enough to stimulate a pro-innovation cultural shock-change. What distinguishes companies in innovation-rich countries is a tolerance for failure that is fundamental to the creative process. Nevertheless, this mindset is antithetical to that of aspiring entrepreneurs in developing countries.

In generating a sense of policy urgency about the innovation performance gap between India and its peer countries, rankings and indices can be helpful. The yearly Global Innovation Index (GII), a widely cited reference on the subject, has recently released its seventh edition. It adopts a broad view of innovation in measuring seven analytical pillars covering capabilities (inputs) and results (outputs). The 2014 report emphasizes the “human factor,” acknowledging the role of the individual in innovative capacity – as mentioned earlier.

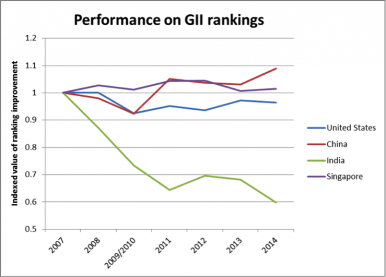

There are many stories behind seven years of GII data. Few, however, are more compelling than trends in India and China over this period. Figure 1 depicts the ranking performance of four dynamic global economies. The indexed value approach creates a “starting line” against which each country’s yearly performance is measured relative to its original position. The chart shows that both China and Singapore improved their rankings, with China having more volatility during the financial crisis. The United States slipped at the beginning of the crisis and has made slow progress recovering. Most notable is India’s dismal performance, flattening after a precipitous decline during the crisis but more recently continuing its distressing trend.

Figure 1.

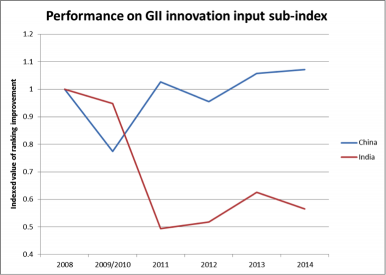

The performances of China and India in the innovation input and output sub-indices are shown in the next two charts, with stark differences. First, the two diverge in innovation input trends (Figure 2). Components of this sub-index include government effectiveness (India ranks 82 of 143, 15 places behind China), regulatory quality (India ranks 108 of 143, 16 places behind China), and ICT access (India ranks 111 of 135, 37 places behind China). India’s performance on most metrics has been consistently poor.

Figure 2.

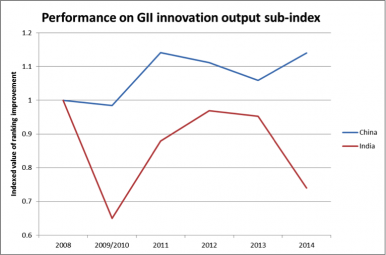

Innovation outputs include development and dissemination of knowledge and “creative” goods in particular. India is again outperformed by China (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Despite its low rankings in the GII, India appears to have a healthy startup environment. Nasscom chair R Chandrasekaran argues that India is becoming an “innovation destination,” and that the next generation of IT innovation will occur locally as business increasingly address the unique challenges facing domestic organizations. These ambitions will not be realized without robust policy intervention. The GII’s comprehensive metrics highlight a range of dimensions in which India has room for improvement. The usual constraints – infrastructure, regulation, and market functionality – continue to hamstring growth. However, improvement in India’s innovation is unlikely unless there are significant cultural and institutional changes, including attitudes towards experimentation, risk-taking, and possible failures. If this creative awakening occurs in both the public and private sectors, India will be positioned to outpace its faster-growing but potentially less innovative peers.

Asit K. Biswas is distinguished visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. Kris Hartley is a doctoral candidate at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.