A common saying about Herat, Afghanistan is that you cannot stretch out a leg there without “poking a poet in the ass.” In her 2002 book The Sewing Circles of Herat, British journalist Christina Lamb attributes the quote to Ali-Shir Nava’i, a leading patron of the arts in fifteenth century Afghanistan. Khaled Hosseini borrows the line in the first chapter of A Thousand Splendid Suns. Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, thought the quip clever enough to recount in his memoirs, the Baburnama.

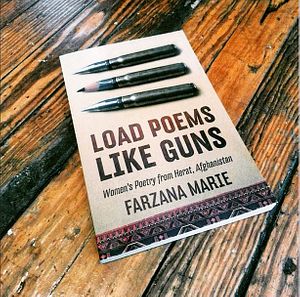

Farzana Marie, who first traveled to Afghanistan as a volunteer teacher and then as a member of the U.S. Air Force, repeats Nava’i’s line in the introduction to her recently released collection of poetry. Compiled, translated, and edited by Marie, Load Poems Like Guns: Women’s Poetry from Herat, Afghanistan brings together a selection of works from eight Afghan women who have preserved, and are reviving, Herat’s cultural heritage.

Load Poems Like Guns begins with a brief introduction to Herat’s literary history and an overview of the struggles of its women poets through the dark days of Taliban rule. The tragic story of Nadia Anjuman, a poet murdered by her husband a decade ago, serves as a reminder of the very real danger women, not just the poets, still face in Afghanistan.

Anjuman took her pen name directly from that of Herat’s esteemed literary society Anjuman-e Adabiy-e Herat, which was formed in the 1930s. Born in 1980, Anjuman began writing poetry, encouraged by her family, as a child. But when the Taliban took control of the city in 1995 Anjuman, who was in eleventh grade at the time, was forced to move her literary ambitions underground. She and a few other women poets gathered in secret, carrying sewing baskets to disguise their notebooks.

After the fall of the Taliban, Anjuman entered Herat University to study openly with the same professors who had risked their lives to nurture the secret circle of women poets under the noses of the Taliban. In 2004 Anjuman was pressured into marrying another student, who Marie characterizes as “skinny and a poor student.” A year later, Anjuman published Gul-e Dudi (“Smoke-Bloom”) the first book of poems by a woman in Herat after the Taliban. What should have been a triumphant moment was marred by Anjuman’s unhappy marriage. While her family had encouraged her literary ambitions, her husband and his family did not appreciate her burgeoning success. Later that year, during a dispute in their home, Anjuman’s husband beat her to death. He served a single month in jail for the crime.

Marie argues in her introduction that Afghanistan’s extensive suffering — through war and conquest — has “strengthened the literary community’s resolve to hold even more tightly to the heritage of words that cannot be destroyed with tanks or rockets.” This this evident nowhere more than in Anjuman’s poems, which are all tinged with darkness:

No one anywhere notices or cares whether / I cry, whether I laugh, whether I die or am still

But Anjuman, and her fellow poets gathered in the pages of Load Poems Like Guns, also hint at hope.

One thought of the day I will break the cage / makes me croon like a carefree drunk until

they can see I am no wind-trembled willow tree– / an Afghan woman wails and sings, and wail and sing I will!

–Both quotes from Nadia Anujman’s poem titled “Makes No Sense” (1999)

In Load Poems Like Guns, Marie beautifully presents her English translations across from the original Dari poems. Marie prefaces each section with a biographical note about each poet and provides specific notes on the translations. She gives helpful hints on the context and imagery in the poems as well. While Marie writes that “imperfection may be the most dependable trait of any translated poem,” she has succeeded in bringing out both the aching sadness and unbound joy contained in her subject’s poems.

You can read The Diplomat’s interview with Farzana Marie in the April Issue of The Diplomat Magazine.