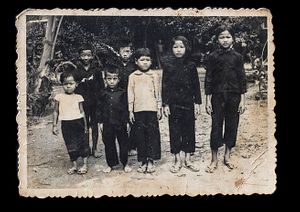

Two years before April 17, 1975, when Khmer Rouge soldiers marched into the capital of Phnom Penh and ushered in the darkest era in Cambodian history, someone took an ominous photograph.

In the picture, which has now been preserved in a searchable digital archive called Found Cambodia, a group of small children are dressed in the all-black uniform of the Khmer Rouge, who had already established a presence in the countryside.

Many children like these would become the brutal foot soldiers of the regime. “I loved the black clothing then but now I hate it as it reminds me of a hard life of slavery and poverty,” one of those pictured recalls in the caption, published online.

Charles Fox, the British photographer behind Found Cambodia, began photographing hundreds of images like these after discovering the private collection of one Cambodian family in the mid 2000s.

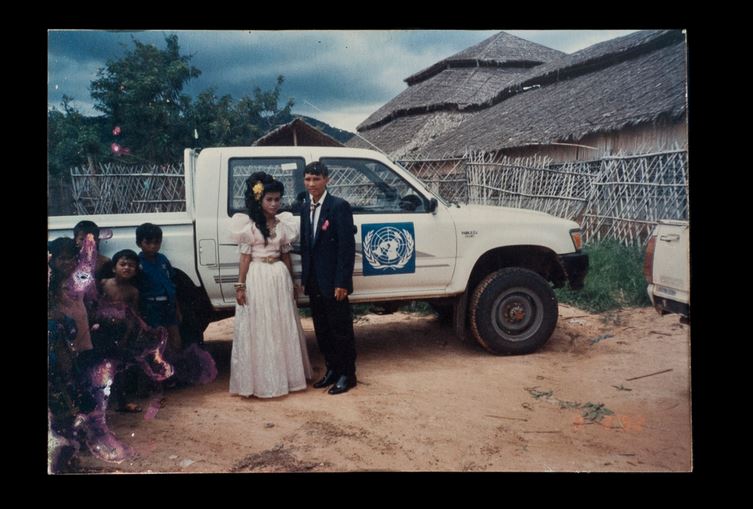

The resulting photo project tells the story of the turbulent past few decades through diverse vignettes from everyday life — from the school report card of a young boy killed by the Khmer Rouge to a wedding shoot set in a refugee camp.

The resulting photo project tells the story of the turbulent past few decades through diverse vignettes from everyday life — from the school report card of a young boy killed by the Khmer Rouge to a wedding shoot set in a refugee camp.

This week, 40 years on from the start of the communist regime, Poppy McPherson spoke with Fox about how the collection began, what it reveals about Cambodian society, and the ethical issues surrounding ‘found photography.’

Was there a particularly moment, or image, that inspired the project?

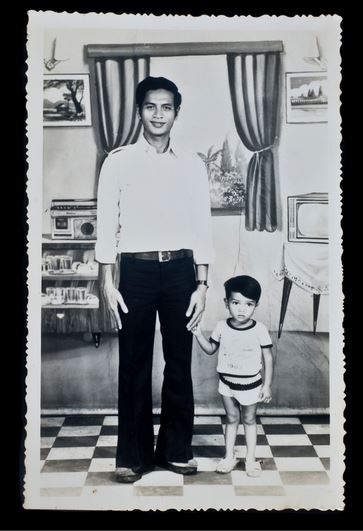

I met this Khmer artist Yanny So [in London] and we clicked – I’m a photographer and he’s an artist so were shared a lot of interests. I went to visit him and his family and friends many times, and he started to show me these old photographs. The one that clicked was a portrait. It was a portrait of his father before the Khmer Rouge. It was really badly damaged and he said to me, “Can you fix it?” And that was the ‘aha’ moment. Because these images were getting damaged. No, I couldn’t fix it, but I could preserve other pictures.

How did you go about finding the other photographs?

It just happened. I’d walk into a shop, for example – I love the way in Cambodia, more often than not if you have a shop it’s your home as well – and family pictures would be on the wall. I’d get interested in the pictures and get talking to people. It’s not like hunting for things or chasing a story. I don’t have a deadline. I get interested in themes and ideas but I’m not particularly looking for a photo to document something. It has to grow organically.

Why did you choose the name ‘Found Cambodia’?

Why did you choose the name ‘Found Cambodia’?

There’s this notion in photography of ‘found photography.’ It comes and goes. It was hot for a while, and then not so hot. I never really cared whether it was hot or not. Photography projects in the past, ones similar to mine, were focused on this notion of finding an image. I was interested in the narrative that went with it. There was a German photographer who found a stash of images in [a] dumpster in China and photographed every single one of them and put them on a multimedia slideshow. But other than the image there was nothing else to it.

What images did you find that tell a particularly moving story?

There’s a photograph of a Cambodian man in his fifties paragliding on his first foreign holiday. I think it was in Phuket. If you put this photo in a European or American context, or any developed world context, it probably wouldn’t be that spectacular. But it was his first holiday, and he said he lost so much that now Cambodians are just trying to do everything they can. He was scared to go paragliding. For me, this picture symbolizes a regrowth and a joy in life despite such terrible loss and trauma.

You mentioned that one of the people whose photographs you collected thought that ‘Found Cambodia’ could have a second meaning: helping find family members and friends separated by the Khmer Rouge.

Vira Rama [a Cambodian American who donated a large collection of pre-Khmer Rouge images] went to his family first and asked, “Can we allow Charles to use these photographs in his project?” His mother asked him what the project was about and he said “found.” She was like, “Oh, wow, ‘found’ – people can find us, reconnect with us.” That was her interpretation of it. While I’m making a nod to a certain style in photography, she was making a more personal nod to something about her life. Now I never set out for the project to do that. But I find it interesting. There’s a reality TV show in Cambodia where they reconnect families. It’s interesting that 40 years on [from the Khmer Rouge regime] people are still trying to reconnect.

The idea of the searchable archives is to document changes within Cambodian society. What observations have you made?

The idea of the searchable archives is to document changes within Cambodian society. What observations have you made?

I don’t think I have enough pictures to draw any concrete conclusions yet but I have witnessed a lot of things in photography and society that I was unaware of. For example, when you see someone cut out of a photograph once you can think it’s a one-off. But when you see it multiple times, and the reasons for the individuals being removed are similar then you start to see cultural trends. People would say: “I don’t want to see that person anymore” or “I have bad memories of that person.” I get the impression that it’s the physical act of cutting that closes the relationship.

I was also unaware of painted photography. It would be good to understand: was this a trend from before the Khmer Rouge or was it developed afterwards as part of a desire to have color photography? What becomes apparent to me is the need to create and rebuild [after the Khmer Rouge] and work through the myriad imported cultural influences – the studio portraits feature Indian styles of clothing and futuristic styles – as well as trying to draw on what existed in Cambodia before.

Is there an ethical question about the ownership and copyright surrounding ‘found’ photography and how do you address that?

When you have a physical photograph, one of the things I don’t ever want to do is take that photograph. When I go and take photographs I do it in people’s homes. Once I had so many I had to take them home and I found that quite a stressful experience. It’s a lot of responsibility because these are often the only copies that people have. By photographing the photograph, I’m making a visual record of the image and I then ask people if I can use them in the project. I don’t own their image, I own an image that I make of an image. And that image is used as a way of preserving and archiving the originals.

Poppy McPherson is a journalist working for Coconuts Media in Southeast Asia. All images used by permission of Charles Fox.