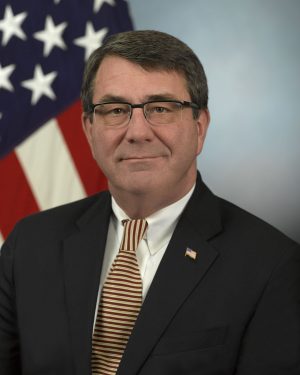

Pentagon strategists obsess about the future of war; it’s their job. The Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, does as well, and as he traveled through Asia for meetings with U.S. allies last week, he clarified his vision for the next phase in the U.S. rebalance to Asia as calibrating the U.S. military presence in the region, not just toward the modern, but the hi-tech. The Pentagon is making a bet that the future of war in Asia is going “high end.”

Before accusing the Pentagon of warmongering or making the region a powder keg, let’s remember that a defense budget must be submitted to Congress every year, and that budget must contain everything the Department of Defense (DoD) thinks is necessary to man, train, and equip U.S. warfighting commands with what they need to defend U.S. interests. How should one go about such a weighty task? Imagining plausible future conflicts (that is, the future of war) helps DoD figure out what types of missions the military might be called on to execute. If you have a sense of these likely missions, you can then take a reasonable guess at what the U.S. military’s size, composition, and concepts for employment should be. You can’t know the future, of course, but as long as the military is going to spend billions of dollars to defend the country from threats that arise, you’ve got to try, and you’ve got to hedge against the plausible worst case scenarios. It’s hard to imagine a method for determining the size and shape of the U.S. military—and corresponding defense budget—without imagining the ways in which the U.S. military might be asked to fight in the future.

Secretary Carter’s comments during his trip to Asia reminds us that when it comes to imagining possible conflicts in Asia, regional trends point toward militaries preparing for hi-tech combat. Precision-guided munitions—ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and missile defense—have proliferated throughout the region and pose distinct challenges to deterrence and crisis management. Added to this is the rapid spread of various types of drones—aerial and undersea variants—the development of next-generation missiles like hypersonic glide vehicles, cyber and electronic warfare capabilities, and a burgeoning arms race in aircraft carriers. These individual developments are familiar to most Asia defense watchers, but collectively they paint a picture of militaries in the region trying to out-modernize each other.

For decades, the U.S. military presence in Asia has helped play a stabilizing role by dint of not simply its commitments to allies, but its military-technical superiority over all potential challengers. What Secretary Carter and his Deputy Bob Work have taken pains to emphasize is that the above trends in military technologies, combined with military concepts that use them to target U.S. and ally vulnerabilities, increasingly challenge U.S. superiority.

Logically, then, a minimally necessary condition for the United States to continue to play a stabilizing role in the region is to find a way to offset the technical advances of any would-be aggressors. The United States is not militarizing the region; the region is militarizing and the United States must find a way to play a stabilizing role as it does. The U.S. rebalance to Asia was intended to send a signal that the United States is committed to continued peace and prosperity in the region, but what that requires of the United States over time may vary.

U.S. commitments need to be credible, and credibility requires sufficient capability. As the region’s militaries modernize, the United States must adapt. Welcome to the next phase of the rebalance.