At the end of 2012’s The Act of Killing, director Joshua Oppenheimer and Anwar Congo, a nationalist gangster who has admitted to hundreds of killings in Indonesia’s anti-communist purges of 1965 and 1966, stand alone on the roof of a handbag store in the Jakarta night. Congo points to the spot where he executed many of his victims with the help of local militias, while the military looked on. The massacres left a million people dead, most of them not the hardened communists who had attempted to overthrow President Sukarno in a coup d’etat, but unlucky civilians pulled from Indonesia’s communities, neighborhoods, and homes.

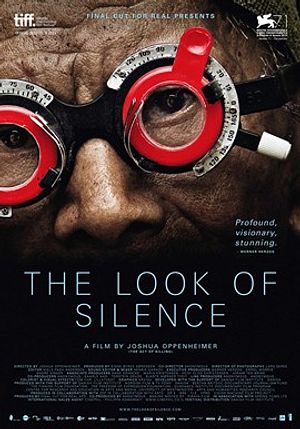

That’s where The Look of Silence, Oppenheimer’s follow-up, takes us. Killing’s characters indulged themselves in the choreography of violence. Our hero in the companion film, Adi, a strong-willed optometrist, goes from door to door confronting the killers, searching for answers in the death of his brother, Ramli. Where Killing was expansive, a high school reunion of embittered, washed-up gangsters, Silence is intimate, filmed in box-shaped stucco houses where blinds blot out the afternoon sun. Killing’s sequences were crowded and chaotic, gangsters jostling for position in the frame as they re-enacted atrocities and rallied on dusty streets packed with rickshaws. There are rarely more than two people to a shot in the companion piece, with only the incessant feedback of cicadas in the background to keep them company.

Sometimes, Adi happens upon the killers and their families by surprise. More often than not, he shows up as a professional, launching into questions only after he puts his optometry glasses on an unsuspecting patient.

These interrogations become an obsession. At night, cicadas blaring in the darkness, Adi watches Ramli’s killers re-enact his brutal murder on the banks over and over, a scene which Oppenheimer filmed several years ago. His bereaved mother and invalid father, both pushing 100, have no idea what he’s doing. Oppenheimer, unusually chatty for a documentarian in the first film, merely follows, and invites us along.

That trip – from the banks of Snake River, the site of Ramli’s death, to the house of Adi’s uncle, who jailed condemned men destined for the killing fields, including his nephew – is not for everyone. In many ways, it’s more disturbing than the first installment: what Silence lacks in physical gore, it makes up for in the psychological wreckage that’s left from the tragedy. From the moment the lights dim, no one is spared Adi’s optometrist’s glasses, a mirror for the massacre itself.

But that doesn’t mean we should look away. On the banks of Snake River and the dense thicket of trees that surround it, life flourishes. The tragedy puts the troubles of everyday life into perspective. Adi’s mother can laugh about the incontinence of her invalid husband, mostly blind and deaf, who can’t even remember Ramli. Adi himself doesn’t even get flustered when his children come home from school suggesting that the killings paved the way for Indonesian democracy. There’s something jovial about his manner and even in Oppenheimer’s camera work. Only a handful of scenes take place at night. That can’t be an accident: those who reject Adi are dressed in shadows, while light beams upon those who understand.

That’s an appropriate choice. Reconciliation is messy, and, by nature, is a process of exclusion. The Look of Silence doesn’t let us escape that.