Dramatic public protest of worker repression is a well-known theme in the history of South Korea’s labor movement. One of the best known and dramatic of protests was, of course, Jeon Tae-il’s 1970 suicide by self-immolation. To protest highly exploitative working conditions in South Korean factories, particularly the conditions in the Seoul Peace Market, Jeon lit himself on fire and ran through the streets of Seoul shouting, “Comply with labor laws!” and “We are not machines!” (See the scene from A Single Spark, starting at around 4:20, of Jeon’s protest by self-immolation.)

Other forms of public protest include long-term occupations of recognizable landmarks: cranes, jumbotrons, and building rooftops. Though not nearly as eye-catching as protest by self-immolation, they are still highly visible, public protests against objectionable working conditions. And they persist today.

While the literature on protest and social movements has emphasized the institutional or structural factors of organized labor and collective action, too little attention has been given to the cultural elements. Indeed, in order to understand labor in our post-industrial world, the cultural or expressive elements must be carefully and systematically studied. A relatively new focus in the literature on South Korea’s labor movement, this is precisely what professors Jennifer Chun and Judy Han, both of the University of Toronto, are doing. A presentation of their recent work was made at a recent workshop in Toronto.

While labor conditions are a far cry from what they were in the early years of South Korea’s highly compressed industrial development — thanks in large part to South Korea’s labor movement and the efforts of people like Jeon — laborers face a new sort of challenge: the downwards pressures of global capitalism and neoliberal reforms. Much like the rise of labor market “dualism” (a dwindling core and rising informal sector) in the traditionally union-strong countries of France and Germany (analyzed in a 2010 article by Bruno Palier and Kathleen Thelen), informal and precarious employment is on the rise in South Korea — but not without symbolic and highly visible resistance.

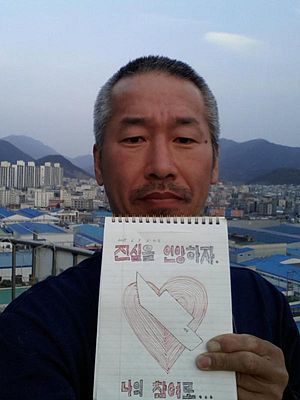

Enter Ja Gwang-ho.*

Kyunghyang Shinmun reported on Monday that, as of Tuesday, Ja holds the record for longest high-altitude sit-in protest. Since May 27, 2014 Ja has sat atop a chimney some 45 meters off the ground to protest what he sees as the unjust treatment of union workers at the now defunct Star Chemical, a provider of synthetic fibers. In 2007 the company went bankrupt and was bought out by Starplex. During acquisition negotiations, Starplex allegedly promised to (re)hire the 800 unionized employees. However, instead of hiring all of them, Starplex unilaterally moved to have 228 employees “voluntarily retire.” Twenty-eight of the 228 refused; they were subsequently fired. Eleven of these 28, including Ja, have continued to fight what they perceived to be an unjust move by Starplex. Ja, unlike the others, took his fight to new heights — literally.

Whether they will win the fight with their employer is yet to be seen. The Kyungyhang piece notes that the 28 former employees and Starplex have yet to reach a satisfactory resolution to the issue. For now, Ja remains atop his perch, continuing his symbolic protest.

*A previous version of this article misspelled Ja Gwang-ho’s surname.