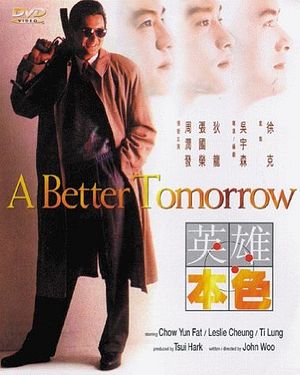

Few films have had the impact of the Promethean 1986 gangster movie A Better Tomorrow. This Chinese classic was so good it cemented the fame of director John Woo and actor Chow Yun-fat, so violent it became the reason for the Hong Kong motion picture rating system, and so original it sparked a new film genre known as “Heroic Bloodshed” — a genre that’s not only dominated Hong Kong action movies ever since but managed to draw Hollywood, that titan of film galaxies, into its orbit.

Also impressive is the fact that, unlike many movies of the 80s, its plaudits have increased over time. In 2005 the Hong Kong Film Awards celebrated 100 years of Chinese cinema by asking 101 filmmakers and critics to compile a list of the best films in Chinese cinematic history. The 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town topped the list, followed by A Better Tomorrow.

The story follows a Triad gangster named Sung Tse Ho and his criminal friend Mark Gor, played by Chow Yun-fat. Ho’s little brother, Sung Tse Kit, is a Hong Kong police inspector played by Leslie Cheung (who later became one of the biggest names in C-pop history). After Ho is betrayed and arrested, Mark slaughters those responsible, but has his kneecap blown out as he is walking away. Meanwhile, the mastermind behind the betrayal takes control of the Triads and has Ho and Kit’s father killed. Upon release, Ho faces a choice between going straight and repairing his relationship with his kid brother, who still blames him for their father’s death, and teaming up with his old friend Mark to exact revenge.

Part of the film’s attraction is its ability to stun, and not simply with excessive gore. Film critic for the L.A. Times Kenneth Turan once described the deaths in The Godfather as Shakespearean, meaning that they “continue to shock no matter how often we’ve watched them coming.”

The violence of A Better Tomorrow is the same. It’s startling, not because we haven’t been inured to cinematic carnage, but because its deaths are rarely frivolous. Even as bad guys are being blown across the room, there’s a sense of heroic disquiet familiar to anyone who follows Game of Thrones. No matter how impossibly skilled the hero seems, he’s not invincible.

The film also stuns with emotional depth. Released from prison, Ho takes work as a taxi driver in an effort to go straight. One day, he runs into his old pal Mark, who now has one good leg and works as a lackey for the man who betrayed Ho and killed his father. When Ho realizes what Mark has become, the shame on the face of actor Chow Yun-fat, who plays Mark, is absolutely crushing. Still, they embrace and Chow displays such bashful happiness at seeing his old friend that one cannot help but smile. However, when Ho tells Mark he isn’t interested in his old life, Mark realizes he is now truly alone, and slides into his chair in a pall of defeat. This emotional gear shift and sudden reversal by Chow is one of my favorite scenes. It’s also quintessential Heroic Bloodshed as it conveys the beautifully melancholic echo of incredible violence.

As the name suggests, Heroic Bloodshed, or Hong Kong Blood Opera, deals in the currency of virtue and violence. Specifically, criminal honor and balletic slaughter. Rick Baker, who coined the term, defines it as “a lot of gun play and gangsters” with “lots of blood. Lots of action.” The clouded psychologies, maelstroms of blood, and lusty urban scenes are an acquired taste, to be sure, but even if that isn’t your thing it’s interesting to note just how deep its relationship with American cinema runs.

For one thing, Heroic Bloodshed borrows heavily from its American precursor, Film Noir. The urban grit, moral ambiguity, and themes of betrayal are all there, as well as familiar stock characters such as the hard-boiled cop, the good-hearted gangster and even the naïve chanteuse, such as Sally Yeh’s character in John Woo’s 1989 masterpiece The Killer. However, unlike Film Noir, comeuppance is practically a mythological concept in Heroic Bloodshed, with protagonists often dead or arrested by the time the credits roll.

This penchant for gratuitous violence and formulaic plot lines means many Heroic Bloodshed films easily go wrong, and a bad Blood Opera is bad indeed. As with pornographic films, plots become little more than risible pretenses for smut (the smut here being violent rather than sexual), and action sequences are so flamboyantly over-the-top they morph into pompous modern-day adaptations of wuxia (Chinese magical martial arts films). The spray of endless bullets, fantasy gun fu, and obligatory Mexican standoffs make for ample facepalming.

A good film, on the other hand, has the emotional depth and measured physical flair of a Broadway musical, and such gems have whispered into the ears of American filmmakers for decades, helping generate a number of Western classics. These include films like City on Fire (1987), which inspired Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992); The Killer (1989), which heavily influenced Luc Besson’s Léon (1994); and Internal Affairs (2002), which Martin Scorsese adapted into the 2006 film The Departed.

More direct crossovers include Face/Off and Mission Impossible II, both by Woo, which introduced Westerners to the genre’s poetic combat. Or Jet Li, who gained Hollywood recognition after the 1998 film Hitman. Or, arguably, Jackie Chan, who went international with the 1995 film Rumble in the Bronx, which leans heavily on Heroic Bloodshed tropes (albeit comedically).

A Better Tomorrow’s 30th anniversary is months away. If you haven’t yet, watch it.