The subject: a man in his 70s who presided over an organization which, during his time as chief, became a global force. According to his detractors, however, he was unable to resist the temptation to convert his power and influence into money and assets. In the space of only a few years, it is claimed that he created and sat in the center of a network which filtered off billions of dollars illicitly.

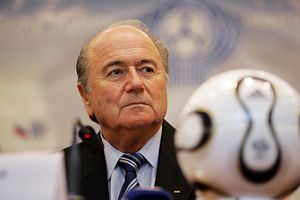

This description fits both Chinese leader Zhou Yongkang, and Sepp Blatter, current head of the international football body FIFA. The difference, of course, is that while the charges against Zhou have been formally dealt with (up to a point) in a criminal investigation and court case, with the sentence handed out on camera in late May, for Blatter the charges remain accusations.

The other difference is that the issues around Zhou were dealt with internally from the start, first through the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and then by the Chinese courts. Swiss-based FIFA, by contrast, is being investigated primarily by an external force: the American Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI is involved because some of the alleged illicit transactions were routed via the United States and made in American dollars, thus falling under U.S. jurisdiction. It is interesting to speculate whether any of the money associated with Zhou went a similar way, opening up this intriguing possibility of China-U.S. cooperation.

Parallels between the Chinese and Swiss case are not just diverting speculations, however. They do say something about the similarities, and differences, when it comes to corruption and corruption management inside and outside China. In the case of FIFA, the entire organization has effectively stood on trial over the last few weeks. Blatter himself announced his resignation and now recognizes that profound, fundamental reform of the institution itself needs to be undertaken before his planned departure some time in the next few months. The underlying assumption is that in allowing this amount of claimed larceny right at the top, FIFA as an entity failed. Simply nailing charges on specific individuals only solves part of the problem. After they are dealt with, the larger question is how this sort of activity can be prevented from recurring within the institution.

For the Communist Party, in the case of Zhou and his reputed allies, there has been no such discourse. The prevailing idea is that the Party was the victim of their bad deeds, just as it was the victim in the past of Mao-era schemes under figures like Lin Biao, or the ill intent of counter-revolutionaries in events like the 1989 protests. There seem to be no major new systems of accountability or institutional changes being proposed after the downfall of Zhou. Nor is there any sense that questions are being asked about how, if all the claims against him were true, the Party accounts for why these crimes were allowed to happened, and how the CCP plans to ensure they never occur again.

This is not to deny that this might all be happening internally. But if so, very little evidence of it has surfaced. The Party seems to continue to have an ad hoc and highly personalized approach to corruption. The Party largely regards itself as innocent and those accused as carrying almost total culpability. It has not used the opportunity presented by Zhou’s downfall and trial to reset this narrative. The questions of why leaders during Zhou’s tenure never spotted his corruption — or decided to do nothing if they did notice — has never been addressed in public discussion or by political leaders in China. It is this more than anything that has fueled the speculation that Zhou’s downfall was for political reasons, that corruption was just a trap to catch him.

FIFA will have some hard times ahead, but the internal admission that it is to blame is a big step toward starting to cure its recent ills. No one pretends this will be an easy path. For the Communist Party, they have proved more effective at dealing with a single individual, and a single case of very high level corruption. But the harder questions have still not been asked. This is why one has to reluctantly accept that this anti-corruption campaign is not over, and is unlikely to be over, until those questions start being discussed. Doing so will almost certainly take the Party leadership into areas and problems which it simply does not want to deal with — a fact that makes even the kindest observer pessimistic about this happening any time soon.