East Asia is experiencing a strange and alarming phenomenon. Exports, which fueled the region’s economic growth for the last three decades, are stalling.

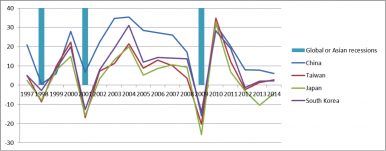

Export have faltered before – in the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis, the global 2001 recession, and the 2008-2009 financial crisis and recession, to name just three. But in each previous instance, exports quickly resumed their double-digit growth rates once global growth returned.

Growth in merchandise exports (year over year)

Source: WTO, author’s calculations (data through year-end 2014)

This time, after rebounding to 30 percent growth in 2010, export growth among Asia’s largest exporters has collapsed. Over the last four years, average gains are in the low single digits. Why the abrupt collapse? Part of it is simply a function of slower global GDP growth, which has clocked in at 3.5-4.0 percent since 2011, compared to a 5 percent rate during the recession-free years last decade. Perhaps more importantly, consumer spending in the U.S. (Asia’s favorite export market) has been running at a 2 percent clip in recent years, compared to 3 percent a decade ago, as U.S. consumers continue to deleverage debt. According to the Wall Street Journal, U.S. imports from China, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea grew by just 1 percent in 2013, down from 13 percent in 2004.

But there must be more to the story. During previous global expansions, these Asian nations had consistently grown exports at rates several times that of their respective GDP growth. This is clearly no longer the case.

There is an alternative explanation. Higher wages and higher living standings have made these economies’ manufacturing sectors less competitive in recent years. This has been obvious with Japan for some time. Now, both Taiwan and South Korea boast per capita incomes in excess of $20,000, placing them in the high-income category. And China has recently climbed to upper-middle-income developing status. Such progress forces change.

Within two years, Japanese carmakers are expected to manufacture more automobiles abroad than they make domestically. Increasingly, Taiwanese electronic firms are setting up shops outside of Taiwan.

Having inked numerous free trade deals over the last decade, South Korea is now the free trade hub of Asia. Exports accounted for 54 percent of its GDP in 2013. Further trade liberalization is unlikely to spur export growth as sharply as in bygone years. Even China’s 12 percent share of global exports (up from 3.5 percent in 2000) is unlikely to continue rising as labor costs push low-end manufacturing offshore.

If exports can no longer pull the Asian train, what can? Asian nations must adopt long-overdue economic reforms that can improve economic efficiency and productivity. Given the rapid contractions of many of their working-age populations, such reforms are imperative.

For Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s “third arrow” should focus on regulatory and tax changes that increase investment incentives for Japanese and foreign firms. As a share of GDP, Japan received only received 3.5 percent of GDP in foreign direct investment in 2013 (compared to 29 percent in the United States).

As it has become increasingly economically interdependent with China, Taiwan has been largely excluded from regional economic integration. Approximately 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports go to the mainland, making slower domestic growth in China problematic for Taiwan. Signing free trade and bilateral investment agreements would help force structural changes to the Taiwanese economy and move it up the value chain.

China wants to rebalance its economy, moving away from exports and fixed asset investment toward growth in household consumption and services. But progress is slow. It must liberalize its financial sector to speed things up. Opening the capital account so Chinese can invest in higher earning assets abroad would increase household wealth and consumption. Opening the financial sector to foreign competition would also increase the efficiency of China’s state-run banking sector. According to economist Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the share of assets in the more than 100 foreign banks operating in China has hovered around 2 percent for more than a decade.

South Korea clearly desires to further develop its service sector, which accounted for 59 percent of GDP in 2013. That’s relatively low for a high-income country and little changed from a decade ago. Liberalizing stringent labor and environmental regulations would be a positive start.

Economic leaders in Asia have long known that the day would come when their economies would have to be rebalanced from exports to domestic demand. Recent numbers suggest that time is upon them now. If Asia’s remarkable growth story is to continue, it can no longer delay making economic reforms.

William T. Wilson is a senior research fellow in The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center.